Finding hidden text in historical documents

A. Sue Weisler

Roger Easton, professor of imaging science, is the go-to guy for imaging cultural artifacts in various states of deterioration. He and his students have enhanced manuscripts all over the world.

The direction of RIT professor Roger Easton’s research changed in 1998 when a manuscript scholar working for Christie’s of New York came to the Chester F. Carlson Center for Imaging Science with a palimpsest in her backpack.

Underneath the text of a 12th-century Christian prayer book lay the erased 10th-century transcriptions of mathematical treatises written by Archimedes in the third century BCE. The palimpsest, or overwritten book, was bound from random pages of discarded manuscripts scraped clean. Copies of Archimedes’ writings had wound up in a medieval recycling bin.

The erased manuscripts in the palimpsest include the only extant copy of Archimedes’ Method of Mechanical Theorems and the only version of his best-known work, On Floating Bodies, written in the original Greek. The Christie’s scholar wanted a sampling of images from the seven treatises for the auction catalog, and she needed the RIT team to disentangle and enhance the undertext.

Easton spent one day that August imaging the manuscript with the late Robert Johnston, archeologist and retired RIT dean of the then-College of Fine Arts. Their collaborator, Keith Knox, then a scientist at Xerox Corp., helped. His sister-in-law at Christie’s had referred the scholar to the group.

They captured a sample of images from the manuscript under ultraviolet and infrared light and processed the information to reveal text and diagrams containing Archimedes’ concepts.

The manuscript sold at auction for $2 million and spent a decade under conservation at the Walters Art Gallery, now Museum. The preservation of Archimedes’ treatises—and other important historical and philosophical writings recovered on the palimpsest—culminated in a 2011 symposium and exhibition and a two-volume catalogue of images enhanced largely by Easton and Knox.

The project gained RIT entry into an inner circle of scholars and conservators. Today, Easton is the go-to guy for imaging manuscripts, maps, musical scores and other cultural artifacts in various states of deterioration.

Demand for the digital recovery of historical artifacts has taken Easton to Egypt, England, France, Germany, the Republic of Georgia, Italy and India to image documents too precious and fragile to move.

He and his students have enhanced religious manuscripts found in a back room at St. Catherine’s Monastery in Mount Sinai, Egypt, the African diaries of Victorian explorer David Livingstone and the 15th century Martellus Map, which may have influenced Christopher Columbus. Discover magazine ranked the multispectral imaging of the Martellus Map at Yale University as No. 74 in its list of the top 100 science stories of 2015. Chet Van Duzer, an independent scholar, led the project.

“The Archimedes palimpsest was the driving force that showed people what could be done and also taught us how to do it,” said Easton, a professor of imaging science. “We had to learn how to collect the data better and process it. The Archimedes is arguably the most significant surviving manuscript in the history of science.”

Urgent need

Spectral imaging recovers faded or erased text by capturing details about the ink and the parchment at different wavelengths. And because different wavelengths of light convey information unique to that spectrum, traces of iron ink, for instance, appear one way in infrared light, another way in ultraviolet, and, perhaps, not at all in visible light. Multispectral imaging collects the different information and recombines them into composite spectral signatures.

Easton uses the near-infrared wavelength to reveal ink in darkened or charred parchment and the ultraviolet wavelength to enhance the visibility of faded text with fluorescence. Instead of reflecting light, a document imaged under ultraviolet absorbs and re-emits light, making the parchment glow beneath the ink.

The collaborator’s imaging system has evolved since the early days of the Archimedes project. The current setup includes a 50-megapixel digital camera, a spectral lens that provides a sharp focus from near ultraviolet to near infrared wavelengths, and different panels of light emitting diodes in 12 bands of color. The camera has optical filters that allow illumination of the object with one color and imaging with another.

“War and climate are the two biggest threats to these documents,” Easton said. “Mali rebels burned the public library in Timbuktu, while ISIS did the same in Mosul (Iraq). There is an urgent need to preserve and document and to have multiple repositories of data.”

One of his collaborators, Gregory Heyworth, a humanities professor at the University of Mississippi, estimates that Europe alone has 60,000 manuscripts in need of attention.

Easton thinks the number is modest. The overwhelming amount of work to be done is compounded by the lack of trained people to do it, he said.

“The Archimedes took us 10 years. That was one manuscript, 177 leaves. It had lots of issues. Then, 161 palimpsested manuscripts at St. Catherine’s Monastery. We started out planning for 135, but we found more during the imaging over the course of the five-year project.”

A happy accident

The emerging field of spectral imaging of historical documents gives RIT an opportunity to capitalize on its imaging expertise and become an international leader and a resource in this area, said David Messinger, director of the Center for Imaging Science.

“We could develop new imaging modalities and new image processing tools and techniques that could be transitioned to the teams that go out into the field,” Messinger said. “Funded graduate students could be doing the cutting-edge research and permanent staff could support both the students and people outside RIT.”

Already students are making a difference.

During work on the Archimedes palimpsest, Kevin Bloechl ’12, ’14 (imaging science) developed processing techniques that Easton now applies to every new project. The story is one of Easton’s favorite anecdotes.

At the time, Bloechl, then a first-year student, asked Easton for something to do over the 2008 winter break instead of bagging groceries. Easton had just received an email from the curator at Walters Art Museum asking him to spend his holiday working on a section of the Archimedes palimpsest the scholars wanted to read. Easton handed the project to Bloechl.

“I said, ‘Here. Go do this,’ figuring he wouldn’t have any luck,” Easton said. “Within four hours, he stumbled upon it. With those images we were able to recover the text that was completely invisible to our normal methods. The scholars described the results as ‘miraculous.’”

Bloechl used one color image composed of red, green and blue light generated by fluorescence from the ultraviolet illumination. The text became legible to scholars after processing those three bands of the color image.

“It was the red-green-blue difference where the text was but only in this one undertext,” he said. “This was a commentary on Aristotle’s ‘Categories’ that was part of the palimpsest.”

His breakthrough changed Easton’s approach. From then on, Easton always imaged the color of the ultraviolet fluorescence. The manuscript absorbed the ultraviolet and emitted light mostly in the blue, some in the green and a little in the red, Easton explained.

Bloechl describes his contribution as a happy accident.

“The pages of the palimpsest had been imaged under illumination at various wavelengths, and all of these wavelengths were being used in processing,” he said. “I forgot to include all of the wavelengths on one attempt. This yielded the initial results that I’d come up with, and noticing improved results, I continued to use this processing over a full page of the palimpsest.”

David Kelbe ’10, ’15 (imaging science) is another student who has advanced the science of imaging historical documents. Kelbe, now a research scientist at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, introduced principles of remote sensing to the statistical analysis of different spectral colors. His techniques analyze the different brightness and wavelengths of light and recombine them to accentuate the contrast of the undertext, he explained.

“Remote sensing has benefited from huge amounts of resources and development over the last decades for the intelligence community,” Kelbe said. “The cultural heritage domain doesn’t have that expertise, but we can bring the same methods and technology to this domain and there is a lot of potential there.”

Kelbe will continue teaching scholars in Vienna and Athens to image documents they wish to recover. He is also ensuring continuity at RIT by teaching his techniques to fourth-year imaging science undergraduates Liz Bondi and Kevin Sacca.

Sacca is exploring solutions for scholars with his senior project. He is developing an inexpensive portable imaging system for scholars to use on site. Sacca will demonstrate a prototype of his imaging-software tool kit at the Imagine RIT: Innovation and Creativity Festival on May 7. Easton looks forward to Sacca’s results.

Messinger sees the potential to connect the dots among the College of Science, the College of Imaging Arts and Sciences, the College of Liberal Arts’ museum studies and digital humanities and social sciences programs, and the Cary Graphic Arts Collection in The Wallace Center. Steven Galbraith, curator of the Melbert B. Cary Jr. Graphic Arts Collection, proposed and championed the idea.

This fall, a new Laboratory for Imaging of Historical Artifacts was established by the Chester F. Carlson Center for Imaging Science with $300,000 from the Chester and Dorris Carlson Charitable Fund. The laboratory will position RIT to advance the science behind imaging historical documents and train more people.

“With the number of manuscripts that need imaging, we need many more systems and many more groups out there doing this work,” Easton said. “We need tech-savvy scholars who can image documents and affordable, user-friendly equipment for them to use. And we need to close the loop between scholars and scientists. It’s really an example of how the humanities and the sciences can work together.”

Past projects

Cultural heritage objects imaged:

- Palimpsests (erased and overwritten manuscripts)

- Archimedes palimpsest 10th century

- Syriac-Galen palimpsest ninth century

- St. Catherine’s Monastery (“New Finds” project administered by the Early Manuscripts Electronic Library)

- David Livingstone’s African diaries

- Scythia, 11th century palimpsest, from the National Library of Austria

- Codex Vercellensis (“Codex A”)

- Les Eschéz d’Amour (The Chess of Love), a 31,000-line, 14th-century French epic poem damaged in 1945 during bombing raids on Dresden

Maps:

- Vercelli Mappamundi c. 1220

- Waldseemüller Cosmographica Universalis 1507

- Martellus World Map c. 1491

Coming up

Roger Easton will present his research this year at several forums. He and collaborator Keith Knox will present the keynote address at the Imaging Science and Technology Society: Digital Archiving Conference at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., April 20, and participate in a forum about the Syriac Galen palimpsest in Philadelphia April 29-30.

Robert Johnston’s legacy

RIT’s foray into the spectral imaging of historical documents was initiated in the 1990s by the late archeologist Robert Johnston, a former dean of RIT’s College of Fine Arts and director of the Chester F. Carlson Center for Imaging Science from 1992-1994.

He was among the first to suggest the use of digital imaging technology to decipher the Dead Sea Scrolls, ancient Jewish texts that hold clues to the development of Christianity.

RIT’s contributions were featured in documentaries produced by British Broadcasting Corp. and the Discovery Channel celebrating the 50th anniversary of the scrolls’ discovery.

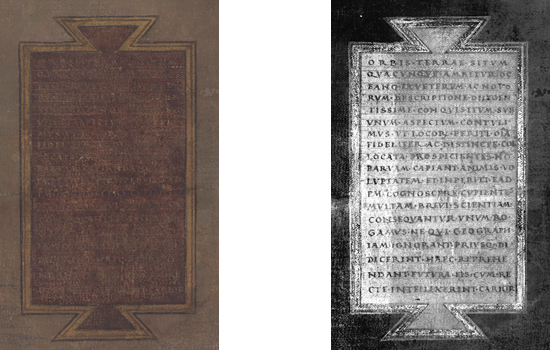

Scholars were unable to read the cartouche on Henricus Martellus’ World Map until Roger Easton processed the images.

Scholars were unable to read the cartouche on Henricus Martellus’ World Map until Roger Easton processed the images.