One step ahead in computing security

A. Sue Weisler

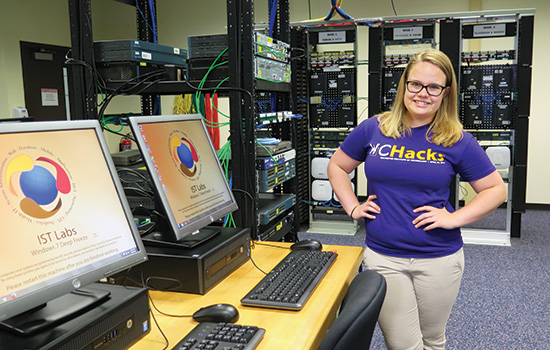

Sarah Jacobus, a second-year computing security student, completed her first co-op at pharmaceutical research company iCardiac Technologies. She sees computing security as a way to be creative.

Kirstie Failey always knew that she wanted to help others, but she wasn’t exactly sure how.

Following her first and only attempt at dissecting a pig, she quickly ruled out medicine as a career path. Yet it was a virus that led Failey to her true passion of cybersecurity.

“I remember in high school, my dad got a virus on his computer and he didn’t want to pay Geek Squad the $75 to fix it,” she said. “I gave it a try and after a little online research, I was able to quarantine the virus and delete it.”

Like a phishing scam, Failey was hooked. Today, as a cybersecurity professional, Failey ’15 (computing security) is helping people on a grand scale. She makes information easily available to those who need it, while simultaneously keeping it out of the wrong hands.

With recent cyber breaches hitting the U.S. government and companies such as Target and JPMorgan Chase, the need for computing security experts has skyrocketed.

By 2019, the United States will need 2.5 million cybersecurity professionals to protect its computer systems, but more than a quarter of those jobs will go unfilled because there aren’t enough qualified workers.

RIT is helping to close this gap as a leader in computing security education. Since the university created one of the first graduate and undergraduate degree programs in computing security and networking a decade ago, the number of students enrolled in the programs has jumped from less than 40 to more than 400 this fall.

In 2012, RIT broke the mold of traditional cybersecurity education by creating the first academic department devoted solely to computing security, a department that integrates faculty from other computing disciplines, including computer science and software engineering.

That department graduated 59 students last academic year, and more than 96 percent were hired at places such as Google, Cisco and the federal government.

“I really believe students studying computing security at RIT are very well prepared to address a lot of the needs in the industry,” said Kirk Striebich ’89 (economics), supervisory special agent in the FBI Cyber Division. “Cybersecurity students at RIT are well-rounded and can think in terms of the whole business or whole government approach to the problem, which will enhance their value on any team approach to cybersecurity.”

An evolving field

RIT wasn’t always cybersecurity focused. Nobody was.

“The Internet and most programming languages were not built with security in mind,” said Yin Pan, associate professor of computing security at RIT. “It was always about delivering information from point A to point B as quickly as possible.”

Once people began buying things online in the mid-1990s, the game changed. Cybercriminals saw an easy way to make money. RIT Professor Daryl Johnson saw the need for security.

The professor began by learning as much as he could on his own and drawing from experiences. He started incorporating elements of cybersecurity into his existing courses and by 2000 he created a class in computer system security—RIT’s first course with a strict security focus.

“This was probably one of the first courses of its kind anywhere,” said Johnson. “A major component of the class was understanding the attacker and the offensive tools that attackers used, as well as incorporating an attack/defend exercise.”

While many of the professors in the B. Thomas Golisano College of Computing and Information Sciences had backgrounds in computer science and networking, hardly any had expert knowledge in computing security because it didn’t exist.

In 2003, seeing this trend toward computing security, professors Bill Stackpole, Sharon Mason and Pan enrolled in a weeklong training course in forensics, hacking and network security.

Trying to wrap their arms around this new content, the trio collaborated the next year to teach RIT’s first course in forensics. The elective course filled up immediately.

RIT professors went to work developing more classes and by 2005 there was enough interest to introduce a graduate degree, followed by a bachelor’s degree two years later.

JP Bourget ’05, ’08 (information technology, computer security and information assurance), took a network security and forensics class during his senior year. He liked it so much that he became one of the first people to enroll in the new computing security master’s program.

For Bourget, the field offered a whole new perspective on computing.

“This was a program for hackers,” said Bourget. “Anyone who is curious and wants to make technology do things it wasn’t designed to do should be in cybersecurity.”

Today, Bourget is the founder and CEO of Virginia-based security company Syncurity Networks. Three of the five people focused on creating incident response management solutions at Syncurity are RIT graduates.

Nationally, RIT began making a name for itself as a perennial contender in the National Collegiate Cyber Defense Competition. The annual “big dance of data defense” requires the best student teams from around the country to fend off cyber attacks from a team of industry professionals.

In 2013, RIT won the tournament and took home the Alamo Cup, beating out top-ranked schools University of Central Florida and University of Washington.

For Jared Stroud, a computing security master’s student, RIT’s dominance at the national cyber defense competition was a major selling point in attending the school.

“I was never interested in making apps or building games—I wanted to break things,” said Stroud, who was also a member of RIT’s 2014 second-place team and 2015 third-place team. “I like the whole idea of working as a team to defend and test a network to help improve a company’s security.”

A social field

For many students, the continuous learning and social nature of the field is what draws them to cybersecurity.

“It’s a stereotype that computing people just sit in front of the screen all day and don’t talk to anyone else. That’s not really the case in our major because you have to be able to work in teams and give presentations,” Stroud said. “Plus the community is so new and small that you become friends with everyone really quickly.”

Sarah Jacobus, a second-year computing security student, sees security as a way to be creative.

Growing up, she enjoyed painting and creating graphic designs on the computer. Today, she uses her creativity to attack and defend computer networks.

“It’s not straight-forward computing,” Jacobus said. “When you’re trying to break into someone’s network, you have to think outside the box.”

New to cybersecurity, Jacobus is still looking for her niche in the field. Last summer, she completed her first co-op at the help desk of pharmaceutical research company iCardiac Technologies in Henrietta, N.Y.

Along with co-ops, students keep up with the rapidly changing cybersecurity landscape by taking part in the university’s two extracurricular clubs—the Security Practices and Research Student Association (SPARSA) and the RIT Competitive Cybersecurity Club (RC3). Students work on projects that aren’t related to school, debate, discuss news of the day and mentor other students.

Both clubs also host attack and defense-focused competitions, which allow students to flex and hone their skills against the industry’s top cybersecurity professionals. Representatives from companies, including Google and Cisco, often sponsor and attend the events to find the best students for co-ops and full-time jobs.

“Sometimes it’s intimidating to go up against upperclassmen that have been doing this for years, but everyone is so nice and it’s always a fun environment,” said Jacobus. “I learn just as much from the competitions as I do in class.”

Great power, great responsibility

In both the competitions and the classroom, students work with real viruses, attacks and exploits in a controlled environment.

Professor Johnson begins most of his classes with mini-reports. Students are invited to discuss a recent event in the world of security.

To start the fall semester, Johnson brought up the Jeep hack. Two hackers had found a flaw in the Jeep Cherokee computer system that allowed them to remotely disrupt someone’s driving—controlling the radio, windshield wipers and even controlling its speed.

“For students, these are a real eye-opener,” said Johnson. “We extended the discussion and talked about how this could potentially be used on an airplane with Wi-Fi connections for passengers.”

In addition to teaching how these exploits work, professors are charged with imparting ethics.

All students in the undergraduate computing security program are required to take a course in ethics and a class in cybersecurity policy and law at RIT. The classes explore the responsibilities of documentation for auditing and examine cases used as precedent for current laws.

“Ethics is something that is driven home in every single one of our classes,” said Failey. “You need to get written permission to access a network that you don’t own.”

Failey now lives in Atlanta and works at the consulting firm Protiviti. Even though she is done with school, she enjoys that her field is always pushing her to learn something new.

“Cybersecurity professionals are trying to find something bad and make it better,” she said. “Plus, you get paid to think all day, which is like the best thing ever.”

By the numbers

- Applications to RIT’s cybersecurity bachelor’s degree program have grown from less than 40 in 2007 to more than 320 in 2015.

- In 2007, there were 34 cybersecurity students in the bachelor’s degree program. This year, there are 124.

- Cybersecurity professionals have an average salary of more than $95,000.

- About 96 percent of RIT’s graduates get jobs right out of school.

- Information assurance/security analyst is the No. 1 fastest growing job out of the top 100 best jobs in America, according to CNNMoney and PayScale.com’s list of America’s best jobs.

Read more

Kirstie Failey ’15 worked in the B. Thomas Golisano College of Computing and Information Sciences before moving to Atlanta in the fall to work at a cybersecurity consulting firm. David Wivell

Kirstie Failey ’15 worked in the B. Thomas Golisano College of Computing and Information Sciences before moving to Atlanta in the fall to work at a cybersecurity consulting firm. David Wivell Fourth-year computing security student Sean McConnell, left, and Jared Stroud, a computing security master’s student, encourage new students to join cybersecurity clubs at the beginning of the school year. A. Sue Weisler

Fourth-year computing security student Sean McConnell, left, and Jared Stroud, a computing security master’s student, encourage new students to join cybersecurity clubs at the beginning of the school year. A. Sue Weisler