War powers and presidential unilateralism examined in new book by RIT professor

The Constitution creates an ‘invitation to struggle’ between executive and legislative branches

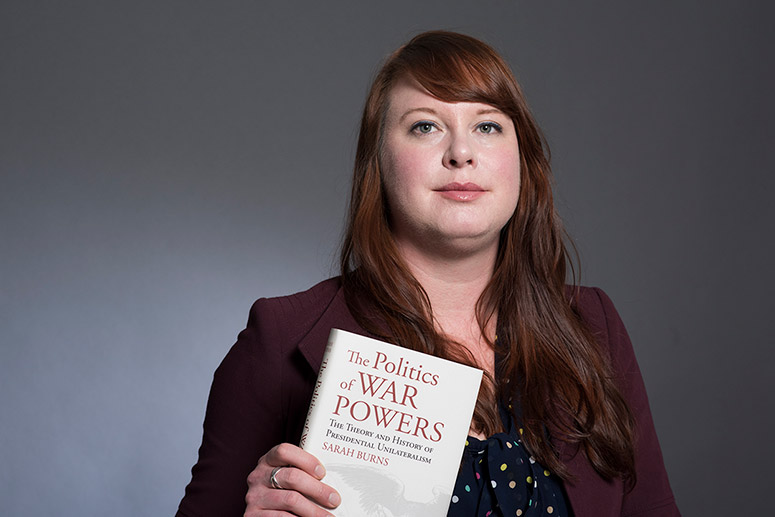

A. Sue Weisler

Sarah Burns and her book, The Politics of War Powers, the Theory and History of Presidential Unilateralism, published by University of Kansas Press.

The debate in Washington continues whether to force President Donald Trump to seek Congressional authorization before taking future military action.

But this isn’t the first time war powers of a president were called into question, says a Rochester Institute of Technology professor whose book details how presidents worked with Congress – or didn’t – prior to foreign attacks.

“In recent decades, war powers have collected in the hands of the executive, leaving him with little check on how and when he uses the U.S. military,” said Sarah Burns, associate professor of political science and author of The Politics of War Powers, the Theory and History of Presidential Unilateralism, recently published by University of Kansas Press.

Burns researched hundreds of years of wartime history, including the presidencies of Abraham Lincoln and Franklin Delano Roosevelt, as well as recent presidencies.

“The branches used to collaborate and discuss grand strategy,” she said. “This has given way since the Cold War as presidents make more rash decisions with a large standing military while Congress looks on from the sidelines.”

By the time we get to the presidencies of George W. Bush, Barack Obama and Donald Trump, we see “a staggering ability to make unilateral decisions in the realm of foreign policy in general and military operations specifically,” Burns said.

“If we look at Obama’s and Trump’s decision making when it comes to Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria, there is not only very little input from Congress but also very little deliberation or grand strategy. The public lacks good reasons for their unilateral decisions and Congress fails to hold them accountable in a serious way. I would go so far as to say that even when Congress has authorized military operations, as they did against Afghanistan and individual terrorists in 2001 and against Iraq in 2002, they failed to provide guard rails or serious limitations to presidential unilateralism.”

Burns became interested in this topic in 2011 after Obama created a no-fly zone in Libya with the United Nations and NATO allies, citing humanitarian reasons.

“He sent a letter to Congress claiming that he had the power to do so as the commander in chief and chief executive,” she said. “He then used evasive words, such as ‘national security’ and ‘regional stability,’ to justify the unilateral initiation of hostilities. Many in Congress expressed anger at Obama’s unconstitutional actions and yet they failed to do anything to either support or oppose him. They were so undecided that they voted to support and oppose his actions on the same day. I was intrigued. Was this something unique to Obama’s relationship with Congress or was this indicative of a trend?”

Burns was optimistic when Trump became president that we might see a more aggressively assertive legislative branch, but she is less hopeful now due, in part, to the dramatic increase in political polarization.

“The best we can hope for is that a Congress dominated by the opposing party will hold a president accountable,” Burns said. “I think we are more likely to see biased or political efforts to tear down the sitting president. People on the left felt that Obama faced a Congress focused on trying to undermine his agenda. I am sure those who support Trump feel the same.”

In her book, Burns demonstrates how difficult it was to craft the Constitution and maintain a healthy separation of powers. Unfortunately, it’s also very hard to fix once it is broken.

She said voting is the best way to remedy this.

“The reason we don’t have members of Congress who stand up to the president is because the voters keep letting them get away with it,” she said. “If we want a more assertive Congress – and we should – we have to be the ones who vote for it.”