Metaproject lifts student designs to professional level

Metaproject 08: Industrial design students re-imagined how dinner out could be interpreted as part of the most recent Metaproject. They created a pop-up restaurant within Good Luck in Rochester.

By partnering with industry, RIT’s industrial design department’s Metaproject teaches students the role of research at every stage of the design process. After eight years, this senior studio has proven itself to be a successful vehicle for fostering innovative thinking and thoughtful product design.

In the Beginning

Metaproject is the brainchild of professor and chair of RIT’s industrial design department Josh Owen, who came to RIT in 2010 just as the Vignelli Center for Design Studies was coming into being.

“I wanted to create a bridge between the newly completed Vignelli Center for Design Studies and the industrial design program. I hoped to leverage the assets of the Vignelli Center to help teach fundamental design lessons. With the Metaproject I would create a platform for students to collaborate with design-centric industry partners of the highest caliber,” said Owen, who chooses one company each year for his senior design studio to partner with.

After more than 20 years as a professional designer and professor, Owen, who has worked around the world, has been able to connect RIT with such powerful brands as Wilsonart International, a creator of laminate surface materials; the Corning Museum of Glass; Areaware, an avant-garde accessories manufacturer; Herman Miller, the iconic furniture maker; Kikkerland, which manufactures products for a variety of consumer markets; Poppin, a maker of unique office products; and Umbra, a Toronto-based housewares manufacturer. Most recently, the students worked with Rochester’s Good Luck restaurant on a unique experiential—rather than product-based—project.

Students are tasked with real problems to solve. As Owen put it, “What itch can we scratch for you? What territory has your company not been able to allocate resources to address? What is too conceptual, future-driven, or just plain out of reach for your team? We want to know how we can help move you forward.”

Students research, design, develop, test, and ultimately build their responses to the issue they’re tasked with. Their projects are critiqued by the industry partners then often ranked into winners and honorable mentions.

All this happens within the confines of the fall semester; in the spring the group exhibits at the International Contemporary Furniture Fair (ICFF), held annually in New York City.

In 2016, RIT’s Metaproject 06 was chosen from 14 university participants to win the Editor’s Choice Award for its show exhibit. One thing that sets the project apart is its branding—the typeface, color palette, the press-quality photography, the 100-page published book that collects the output—it announces itself to the world as much more than a senior project.

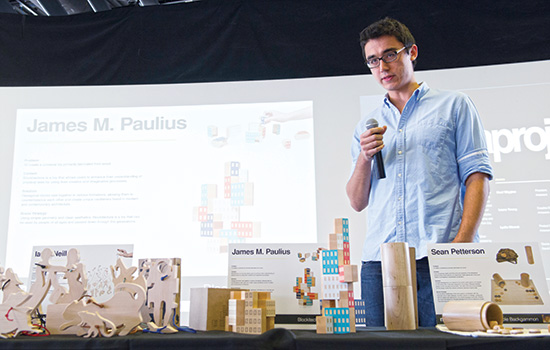

Usually at least one project is chosen each year to be produced by the partner company and put into the marketplace. Blockitecture, toy building blocks, created by James Paulius for Areaware (Metaproject 03), is one of that company’s most popular items and is sold all over the world. Paulius has since created several other related products, the most recent being Blockitecture Tower.

Sticky Memo Ball, a 12-sided sticky-note ball created for Poppin (Metaproject 06) designed by Afifi Ishak ’17, is one of the The Container Store’s top-selling items.

Collaborative Foundation

Veronica Lin ’17 was part of Metaproject 06, which asked students to create innovative accessories for Poppin’s new line of office furniture.

Lin, who now works as an industrial designer with Pensa in Brooklyn, N.Y., focused on creating a foot rest. “I had to think like a millennial who spent a lot of time in front of a computer and not moving,” Lin said. “How could I make that experience better?”

Lin’s Foot Pebble, one of four winners that year, is a solid cork curved foot rest that allows users to rock their feet back and forth as they sit. It’s both functional and playful. Lin had to research ergo–nomics as well as product materials and product dimensions but felt confident doing so because, she said, “by the time you’re a senior at RIT, it’s been ingrained in you how to tackle a project.”

She began drawing ideas and making models, which “in this case were more important than sketching. I needed to see people of all heights putting their feet on it and seeing whether it worked.”

She said that collaborating with her classmates was integral to her research as well. Even though other students focused on designing different elements, she said, “I learned so much about the office workspace when my classmates and I stayed up late at night suggesting ways to tackle products from different angles.”

Ultimately, Lin’s product was not chosen to go to market (that year it was Memo Ball) because of the difficulties of using cork, but it was featured in the international design magazine Azure. These were lessons in themselves since the products have to be able to stand up to marketplace scrutiny as well as actual use.

That’s one of the most important aspects of these kinds of projects within the industrial design program. “Students are exposed to real-world parameters but are safely guided through the process,” Owen said. “In my view, that’s a perfect formula for setting students up for success.”

Beyond Production

The industry partners play a crucial role in helping participants through the marketing and business research part of the program.

“When we traveled to Umbra’s Toronto headquarters, founder Les Mandelbaum, who took his company from his garage to a powerhouse global brand, stood in front of all of the students of the class and told them his personal story,” Owen said. “Our group met with leaders, managers, designers, marketing and communication staff who showed them what works and what fails in the wider conditions of their experience.”

Students were able to touch and feel the company’s products, take things apart and put them back together, see them in the context of the company itself.

Jeff Miller, Poppin’s vice president of product design, said that he was impressed by the “level of inquiry, skill, and technology” that the Metaproject students brought with them.

“I saw quite an amped-up ability in terms of what students could do and bring to the table and in terms of their discussion with us as pros. They were already thinking at a near-professional level about real-world concerns, what we as an industry might be thinking in terms of requirements for our products. The speed they needed to turn these from process into reality with a high degree of technical quality and ability—I couldn’t have done that (when I was their age).”

The hands-on, interactive aspects of Metaproject mean students learn about products from “psychological, engineering, and material perspectives (among others),” Owen said. “By the end of that decoding (period with the industry partners), they have opened a massive window into the machine that is industry that they can more than look through— it is big enough for them to jump into, walk around, and explore.”

Experiential Design

The most recent challenge, Metaproject 08, was different than all the others. Owen connected with RIT industrial design graduate Chuck Cerankosky ’03, co-owner of Good Luck, a high-end restaurant in Rochester named by Esquire magazine in 2016 as one of the top 18 bars in America.

When discussing the project, they shied away from kitchenware, said Cerankosky. “Those can be subjects of get-rich-quick schemes or just some gadget you throw in a drawer. I wanted to look at the restaurant as a whole. What inspires me as a designer is not because I get to design a new plate, but it’s the whole of things, designing the experience.” He views restaurant ownership “as live perpetual industrial design performance art.”

Students worked with Good Luck employees to break down the dining experience beginning with customers getting out of their cars, coming through the doors, hanging their coats and having drinks, all the way through dessert and coffee.

Cerankosky describes it as students creating songs for an album. “The songs could be different, but it had to have a theme.”

“Designing Dining” ended up as a successful, curated dining experience for 60 people. Students built on Good Luck’s “inspired table,” a prix fixe menu that it does a few times a year, and came up with a celebration of seasonality as a theme. They broke into teams in charge of sound and lighting, furniture, parking, coat checking, and meal planning.

“It was a challenging project but really cool that we could bring industrial design principles into a completely different field,” said fourth-year student Fuijae Lee.

Every detail was planned. For example, they determined that coats shouldn’t be hidden away. Coat check became part of the décor, with coats hanging on numbered hangers—which they created and fabricated out of laminate—along guide wires.

At one point, a “reverse pickpocket” team slipped cork coasters—that still smelled of burnt wood where they had been laser cut—into guests’ coat pockets.

Each course began with a change of table cloth, the last being a heat-sensitive cloth that changed color from the warmth of the cups and plates. Other highlights included a bouquet of salad, specially designed wooden platters that held intricate bamboo skewers during the appetizer segment, and a sauce pen from which diners could add flavoring to their meal. “(The pen) was really trans–formative,” said Cerankosky, who added that the pen and the skewer holder will likely be incorporated into the restaurant’s offerings.

Owen said the dinner was not a tough sell, and the 60 tickets were all sold out. RIT Provost Jeremy Haefner, one of the attendees, said it “was a great experience, a big success. The world of design involves not just products but experiences and the way that people engage with each other. This fit the bill nicely.”

(At press, Owen was still determining how to present the program at ICFF in May.)

Metaproject 09 has not yet been revealed. It’s always a mystery to the students prior to the first day of class, Owen said, “and they want it that way—designers like constraints and challenges.”

Much like any design challenge, the unknowns and the failures are part of the process.

But, as Owen said, “These projects almost demand a leap of faith from those outside the design fold. The strongest companies are design savvy. They know the iterative process that we demonstrate—test, fail, repeat until we deliver value and beauty. The companies that don’t take the leap of faith to work with designers tend to make a lot of mediocrity. Or they simply follow trends. We lead by example and teach others to do the same.”

Metaproject 06: Afifi Ishak's Sticky Memo Ball, with 12 pentagonal faces, was a desk accessory presented to Poppin in 2016. Twenty-two students were tasked with creating innovative accessories for the company.

Metaproject 06: Afifi Ishak's Sticky Memo Ball, with 12 pentagonal faces, was a desk accessory presented to Poppin in 2016. Twenty-two students were tasked with creating innovative accessories for the company. Metaproject 03: James Paulius created toy building blocks called Blockitecture when he participated in Metaproject in 2012-2013. The product is now sold all over the world.

Metaproject 03: James Paulius created toy building blocks called Blockitecture when he participated in Metaproject in 2012-2013. The product is now sold all over the world.