Research fuels creativity that powers RIT designers

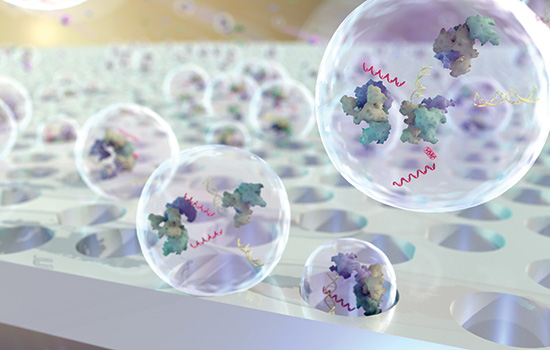

Capturing Science: This image shows exosomes- small vesicles produced by stem cells--being isolated using a nanoporous membrane. The scene was designed by Bradley Kwarta, a medical illustration graduate student. Medical illustration's multidisciplinary connections exemplify why RIT is among top universities working at the intersection of technology, the arts, and design.

RIT is one of the top universities in the nation working at the intersection of technology, the arts, and design. The university’s design programs are world ranked due to innovative students and faculty, along with close ties to industry and alumni.

From Beaux-Arts to Modernism

Designers thrive when they have a working concept of what makes people tick, a context that allows them to shape their ideas by considering what people covet and use—along with a place to focus all of their creative energy.

What provides the fuel for such new ideas? Research.

“Design research is foundational to understanding and meeting human needs,” said Chris Jackson, associate dean of RIT’s College of Imaging Arts and Sciences (CIAS). “The information gained through design research validates ideas. It translates assumptions into actionable knowledge. Applying this knowledge significantly raises the bar on delivering a successful design solution that resonates with users.”

Design research emerged as a recognizable field of study at RIT and elsewhere in the 1960s. Some of the origins of design research are found in the emergence of operational research methods and management decision-making techniques after World War II, the development of creativity techniques in the 1950s, and the early beginnings of computer programs for problem-solving in the 1960s.

“When I first came to RIT in 1963, it was largely a beaux-arts school,” said R. Roger Remington, RIT’s Vignelli Distinguished Professor of Design, referring to the classical decorative style and influences of Paris from the early- to mid-1900s. “The change from a fine arts school into one of modernist design precipitated the dramatic shift from analog to digital and the advent of more intensive research here.”

In 1983, Remington, the author of six books on the history of graphic design with two more in the works for 2018, organized “Coming of Age,” the first-ever international symposium on the history of design, with a particular focus on graphic design. From those early roots, RIT has become a world leader in emphasizing history, theory, and criticism in design education and research, including the acquisition of nearly 50 archives of design’s modern masters.

No other school or institution of any kind can offer such extensive opportunities to learn and research from actual artifacts, rather than reproductions, Remington observed.

These resources complement RIT’s wide variety of creative programs that rely considerably on research, from industrial design, new media design, 3D digital design, and interior design to the fine arts and crafts programs in glass, metal, wood, and ceramics.

Design ‘Explosion’ Fuels Research

“Design has always had this focus on applying research as part of the visual language and the visual dialogue that we’re creating,” said Adam Smith ’01 (MFA computer graphics design), chair of the new media design program and graduate director of visual communication design. “Fifteen years ago, design—especially interactive design—was very ad hoc. Here at RIT and elsewhere, designers were exploring new and different ways of using technology to present information, so in a way early design was a form of research.”

“What we lacked, however, in the early days, was the ability to necessarily understand how to leverage the power of the research methodologies,” Smith added. “There’s a method to analyze, to record and evaluate design research and build those improvements off of it.”

One benefit of the huge explosion in design over the last two decades is that it has enabled designers to refine and hone ideas based on usability, usefulness, and functionality, according to Smith and other members of the RIT design faculty.

“After we started to see things like the iPhone come out, companies like Apple and others were for the first time publishing design guidelines around not just visual styles but also how humans interact with these devices,” he said. “That provided us a compass to take this direction of interaction, visual design, and design language and place it under the umbrella of research patterns.”

User-Centered Research a Key

Alex Lobos, associate professor and graduate director of industrial design, noted that research is essential to making the design process user-centered, iterative, and honest.

“Research can be liberating to designers because it provides important details on how users will respond or react to a product in a certain way, so it doesn’t all fall on the designer,” Lobos said. “In addition to being user-centric, good design has to be iterative so designers can refine their ideas with each stage of the process.”

As an extended faculty member of the Golisano Institute for Sustainability, Lobos noted that researching and designing “green” or environmentally benign products has become even more important in recent years, particularly among younger generations.

“By minimizing waste in the research and design process, you end up with a product that’s very honest and pure,” he said. “Today’s end user will react favorably to that because they can recognize that honesty.”

Lobos arrived at RIT eight years ago from General Electric. Leveraging his industry background, he oversees multidisciplinary collaborations between RIT and a number of partner companies, including Autodesk, the international software company based in San Francisco.

Since Lobos spearheaded RIT’s relationship with Autodesk in 2011, the research and design collaboration has flourished.

He has attended joint conference presentations with company executives as part of Autodesk University, and the company has sponsored several multi–disciplinary research projects that are opening new worlds for people through effective access technology.

RIT is one of only four universities Autodesk has signed a memorandum of understanding agreement with to work together even more.

Lobos also works closely with Stan Rickel, faculty coordinator for Studio 930, a summer co-op in which RIT students research and develop projects from concept to prototype to commerciality. It’s part of the Albert J. Simone Center for Innovation and Entrepreneurship, which helps to advance student ideas and projects through business development programs, funding opportunities, student competitions, and mentoring. A number of these projects has evolved into successful startup companies.

Solutions for the Real World

Design research is enabling RIT students to solve complex, real-world problems—both regionally and far away from Rochester, observed Peter Byrne, administrative chair and professor in the School of Design.

“We’re asking students across all of our design programs, ‘How do you figure it out?’” Byrne said. “The research process is giving our students the skills to develop design toolkits to do some amazing things.”

For example, four RIT students, three from CIAS and one representing Kate Gleason College of Engineering, traveled to Honduras last fall with Mary Golden, interior design program chair, to advance three multidisciplinary capstone research projects and collect information for five other initiatives.

The capstone endeavors stem from RIT’s interior design program’s collaboration with Little Angels of Honduras (LAH), a nonprofit organization dedicated to reducing infant mortality in the Central American country. Last year, under the guidance of Golden and Shannon Buchholtz, adjunct professor, interior design students supplied LAH with proposed interior packages for its campaign to significantly expand a neonatal intensive care unit addition at Hospital Escuela, Honduras’ largest public hospital, including designs for premature baby examination tables and a mobile education unit.

“We had very full days of research and activities at the hospital,” recalled Golden, adding that the projects in various stages of progression use a science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics (STEAM) approach.

LAH’s core mission is to bring optimal conditions for maternal and infant care to Honduras, where the existing high maternal-infant mortality rates are traced to an extreme lack of space and medical equipment, hindering the quality of care.

Designing Solutions for the Smithsonian

Back in the United States, before joining RIT’s industrial design faculty as an assistant professor in 2013, Mindy Magyar managed the design of the Smithsonian Institution’s restaurants and shops, including the Sweet Home Café and Museum Store at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, as a project manager.

“When you’re dealing with politically or culturally sensitive content, research is vital to delivering a culturally authentic narrative and experience,” Magyar said. “And co-design, or participatory design, is necessary to successfully integrate the ideas and interests of varied constituents.”

“An extensive research process—one that is highly collaborative—will guide you to a good result,” she added. “But you cannot define what that result will be without the important input of others.”

Magyar began her professional career as a financial analyst at J.P. Morgan, guiding the portfolios of corporate clients and later proprietary investors through research—a background that has served her well at RIT.

“I encourage my students to think critically, to always consider various perspectives when designing,” she said. “Research methodology provides them with a framework to do this.”

Supporting Traditional Research

RIT design students are developing skills and techniques to succeed through service to more traditional research. As a faculty member supporting the personal health care technology group—a Signature Interdisciplinary Research Area at RIT—Smith is part of a group identifying university projects that will benefit from having design incorporated into university research.

Bradley Kwarta, a medical illustration graduate student, has been designing extraordinary imagery while embedded in RIT’s NanoBio Device Laboratory during the past year.

Under the direction of Thomas Gaborski, associate professor of biomedical engineering in KGCOE, Kwarta is creating stunning illustrations to support the lab’s cutting-edge research that includes developing porous membrane scaffolds for laboratory models of tissue barriers like the blood-brain barrier, the intestinal wall, and the lung, among others.

“I’m actually inserted into the lab so that if I have any questions I can ask the researchers directly, in real time, to get a better understanding of what I’m being asked to illustrate,” said Kwarta, a native of Pittsford, N.Y. “Many times there can be a disconnect between those doing the research and the creative mind, but by being embedded in the lab the process is much more streamlined.”

While Kwarta came into RIT’s medical illustration graduate program with an undergraduate biology degree and once considered medical school, the lab’s research is extremely complex.

“I’m often designing new imagery that has never been created before,” said Kwarta, noting that his highly detailed 3D model of an exosome he illustrated may be the first ever conceived. “I start with doing a lot of research in textbooks and online resources before beginning to develop simple sketches—even if I’m not exactly sure what it’s going to look like in the end.”

Continuing his research and frequently sharing his work with the lab team to make sure it’s on the mark, Kwarta then moves into 3D modeling, shading, and lighting so that his polished illustration can be used for research papers, trade journal articles, or presentations at key bioengineering conferences.

For his thesis, Kwarta is illustrating one of the lab’s major bioseparation projects—creation of a portable hemodialysis system—along with a video animation demonstrating the process.

The level of science knowledge that medical illustrators such as Kwarta need to know to perform their responsibilities has increased considerably as their role and research importance increases dramatically, according to James Perkins ’92 (MFA medical illustration), professor and graduate director of the medical illustration program within RIT’s College of Health Sciences and Technology.

“Medical illustrators need to be able to comprehend the latest research in an obscure topic in molecular biology or cell biology,” Perkins said. “It’s not uncommon for today’s medical illustrators to regularly collaborate with physicians, scientists, and other health care professionals to translate complex scientific information into visual imagery that supports medical education, science research, and patient care.”

While many of today’s medical illustrations continue to be used in textbooks, modern-day medical illustrators regularly find themselves working in three dimensions, creating anatomical teaching models, facial prosthetics, patient simulators, and web-based media.

Keeping Up with Game Engines

It’s not uncommon for program chair Marla Schweppe’s 3D digital design students to have to research and learn how to model hair, steam, or water as “game engines get more and more powerful so they need to include more and more detail.”

“We can use software to animate cloth in a very sophisticated way, and that means our students now need to know something about fabric—how different fabrics move, what kind of fabric is appropriate for certain types of garments, along with the history of costumes,” said Schweppe, who early in her career designed for theater, dance, TV, and movies in New York City and elsewhere.

“To use software that creates trees, our students need to know if a certain tree grows in a particular climate,” she added. “How do animals move? That’s why they take anatomical figure drawing and have to abstract that to wildlife.”

For “live design” and productions, Schweppe said, students must research and learn how to use infrared cameras to track dancers and integrate their images into projections, including how to use facial tracking software for game engines or 3D software, virtual reality, and augmented reality systems.

Students’ work spans computers and video games, virtual reality, medical and scientific simulations, data visualization, and more. Their powerful displays of cascading colors and images often can be seen at city festivals, including the KeyBank Rochester Fringe Festival.

Since graduating its first four students in 2011, the program has grown to 130.

While Schweppe’s 3D digital design program and other programs in RIT’s School of Design are uniquely specialized, each shares an inquisitive and dynamic educational community in which research, creativity, critical thinking, cross-disciplinary study, and social responsibility are explored, cultivated, and promoted to make a positive impact—both in the study areas and ultimately on the society in which we live, according to Robin Cass, interim dean of CIAS.

“There are outstanding design faculty in our college that have so much to contribute to areas of study and research across RIT,” Cass said. “For example, ‘design thinking’ is becoming a popular and important tool used to grow business.

“While in the past, design was brought into the product development process late in the game to ‘doll up’ an already developed product, it’s now being called upon to play a strategic role from the start,” she concluded.

On the Web

Sustainable Design: As an extended faculty member of the Golisano Institute for Sustainability (GIS), Alex Lobos, associate professor and graduate director of industrial design, noted that researching and designing “green" or environmentally benign products has become even more important. Here he is leading a session with Callie Babbitt, an associate professor at GIS.

Sustainable Design: As an extended faculty member of the Golisano Institute for Sustainability (GIS), Alex Lobos, associate professor and graduate director of industrial design, noted that researching and designing “green" or environmentally benign products has become even more important. Here he is leading a session with Callie Babbitt, an associate professor at GIS. Capstone Research: Alexa Boyd, left, interior design; Hannah Lutz, industrial design; and Victoria Tripp, mechanical engineering, pose with Dr. Armando Berlios of Hospital Escuela. They are working on capstone research projects, led by Mary Golden, with Little Angels of Honduras.

Capstone Research: Alexa Boyd, left, interior design; Hannah Lutz, industrial design; and Victoria Tripp, mechanical engineering, pose with Dr. Armando Berlios of Hospital Escuela. They are working on capstone research projects, led by Mary Golden, with Little Angels of Honduras. Growing Program: According to Program Chair Marla Schweppe, left, the 3D digital design program has grown to 130 students currently since graduating its first four students in 2011.

Growing Program: According to Program Chair Marla Schweppe, left, the 3D digital design program has grown to 130 students currently since graduating its first four students in 2011.