RIT engineering alumnus is part of DART team that changed the speed and path of an asteroid

Dmitriy Bekker helped develop imaging and targeting technology for the DART spacecraft

NASA/Johns Hopkins APL/Ed Whitman

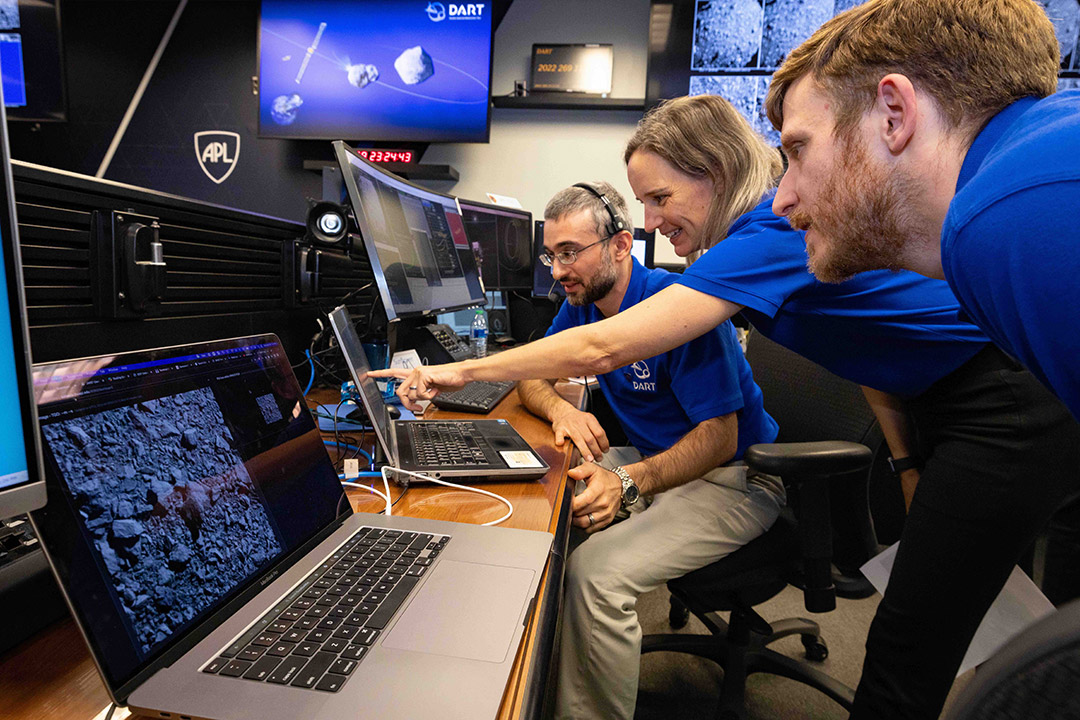

On console in the mission operations center at Johns Hopkins APL, Dmitriy Bekker (left), Carolyn Ernst (DRACO instrument scientist) and Zach Fletcher (DRACO instrument lead engineer) take a closer look at the images the spacecraft's onboard camera DRACO returned of the asteroid just seconds before impact.

It is a powerful thing to redirect a 525-foot asteroid with a spacecraft moving at 14,000 mph, and Dmitriy Bekker was one of the engineers who made it happen.

Bekker ’07 BS/MS (computer engineering) is part of the DART – Double Asteroid Redirection Test team that impacted the asteroid Dimorphos on Sept. 26. Its mission was to test asteroid deflection technology—a means to defend Earth by changing the motion and speed of an asteroid.

“This was a test of planetary defense technology. We collected data from this impact so that we have a better idea of how to do this in the future if our planet is ever threatened,” said Bekker, an embedded systems engineer at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (JHUAPL). The lab is one of NASA’s partners in the development of technology and scientific instruments for space missions.

Last fall, NASA launched the DART spacecraft, built at JHUAPL. DART headed toward the Didymos asteroid system millions of miles from Earth, where it encountered the moonlet Dimorphos. While there was no danger to Earth from this asteroid, it was selected to measure how the small moon’s orbit would change due to the impact of the spacecraft. NASA predicted a 10-minute orbital change; DART shortened the orbit by 32 minutes.

“What was really impressive was that we had Hubble, James Webb, and other telescopes all over the world observing and watching this pre-planned, cosmic fireworks display that we all had a big part in.”

Bekker worked on the imager DRACO—the Didymos Reconnaissance and Asteroid Camera for Optical navigation—and led the development of the high-tech camera’s embedded processing system that was used to analyze images and assist with targeting. He also had a role in developing the displays and screens to visualize the data coming back to Mission Control from the spacecraft.

“We had a great team designing, building, and testing the spacecraft,” he said. “Once we launched and were in space, we had to practice operating the spacecraft. It was like learning to drive a car.”

Except that the car was a 1,300-pound spacecraft.

He learned to “drive” through a combination of coursework at RIT and several diverse and challenging co-ops at some of the top research labs in the country—what he termed an engineering wonderland. At Brookhaven National Lab, Bekker worked on data acquisition software for a large laser system. He then moved to a program at NASA Armstrong Research Center, working on instrumentation for research aircraft, and later interned with the NASA Jet Propulsion Lab, where he would eventually be hired after graduation.

“Many folks in computer engineering go to companies like Microsoft, Intel, or Micron, to name a few,” said Bekker, who is originally from Brighton, N.Y., and who often comes to campus to represent Johns Hopkins APL at the annual Career Fair. “For those that come from a similar background of computer engineering, computer science, and electrical engineering like I experienced here at RIT, there’s a career path out there that needs this background in engineering to contribute to fundamental research.”

And to contribute to work on new space missions.

DART resonated with people because of its easy-to-understand objective. It was simple in its focus of hitting an asteroid, checking if the technology works, and improving for the future.

“NASA is interested in enabling commercial industry to get us back to the moon. And Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab is proposing the instrumentation that might go into these projects,” said Bekker. “I often say that the projects I am working on now, even the DART mission, they all feel like larger and longer senior design projects.”