A Breakthrough in Cell and Virus Analysis: How Electric Fields are Transforming Biomedical Research

In biology and medicine, the ability to rapidly analyze and separate micron- and nano-sized particles, such as bacterial cells and viruses, is crucial. This article delves into a cutting-edge field and reviews the use of electrokinetic methods, particularly for the analysis of intact cells and viruses, showing how they are revolutionizing the field.

In biology and medicine, the ability to rapidly analyze and separate micron- and nano-sized particles, such as bacterial cells and viruses, is crucial. Traditionally, methods such as centrifugation and filtration have been used for this purpose; however, these techniques often have limitations, especially in terms of speed, accuracy, and selectivity. Electrokinetic (EK) methods are a set of advanced techniques that use electric fields to manipulate and analyze particles. This article delves into a cutting-edge field and reviews the use of EK methods, particularly for the analysis of intact cells and viruses, showing how they are revolutionizing the field [1,2].

Why Electric Fields?

At the core of EK methods is the use of electric fields to manipulate particles, such as cells and viruses. Microorganisms like bacteria and viruses have unique electrical properties, which can be exploited using these methods. For example, most biological cells and viruses carry a negative charge under certain conditions [3], which enables them to migrate when subjected to an electric field. This electromigration, known as electrophoresis, is one of several EK phenomena that can be harnessed to analyze microorganisms.

Miniaturized Platforms: Faster and More Efficient

One of the major advantages of employing electrokinetic methods is the ability to miniaturize the analysis platforms. Traditional methods require large, bulky equipment and are often time-consuming. In contrast, EK-based platforms can be miniaturized, allowing quicker analysis and integration into portable devices. This opens up a range of possibilities, from rapid medical diagnostics to environmental monitoring.

Different Types of Electrokinetic Techniques

This article identifies three main types of electrokinetic techniques: electromigration-based methods, electrode-based methods, and insulator-based methods. Each of these has unique characteristics and applications.

1. Electromigration-based Methods: These methods rely on the movement of particles in response to an electric field. One of the simplest and most widely used forms of this is capillary electrophoresis (CE), where particles are separated based on their size and charge. Capillary zone electrophoresis (CZE), a subtype of CE, is particularly effective for separating microorganisms and nano-sized particles, including bacterial cells and viruses [4–7]. The process is fast and accurate, making it ideal for applications where time is of the essence, such as diagnosing infections.

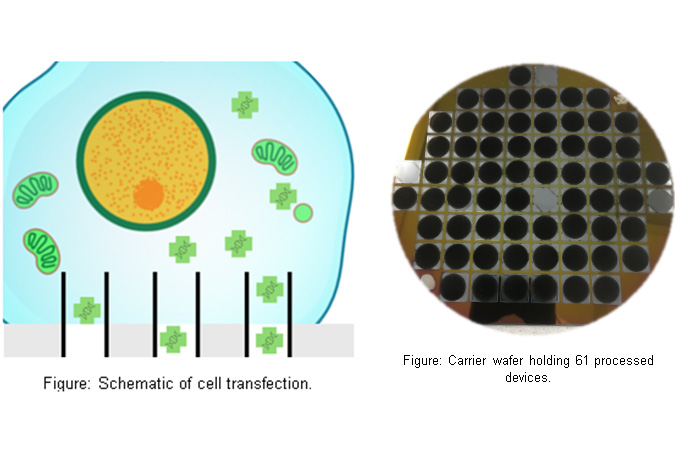

2. Electrode-based Electrokinetics: In these methods, electrodes of distinct configurations are used to create precise electric field configurations that influence the movement of particles. A specific technique within this category is dielectrophoresis (DEP), which can separate particles and microorganisms based on their polarizability. DEP is highly effective in discriminating between similar microorganisms [8], making it a valuable tool for distinguishing between different strains of bacteria or types of viruses [9]. This has important implications for clinical diagnostics, where rapid and accurate identification of pathogens is crucial.

3. Insulator-based Electrokinetics: Unlike electrode-based methods, insulator-based techniques use non-conductive materials to create specific electric field configurations which can trap and manipulate particles [10,11]. This method is particularly useful for concentrating microorganisms from dilute samples, such as water. By exploiting differences in electric properties, insulator-based EK systems can separate particles with high precision, even in challenging environments. This technique also shows great potential for successfully separating highly similar microparticles [12].

Applications in Cell and Virus Analysis

One of the most exciting aspects of electrokinetic methods is their wide range of applications. This article highlights several areas where these techniques are making a significant impact.

1. Clinical Diagnostics: Electrokinetic methods have the potential to transform the way we diagnose infections. For instance, capillary electrophoresis has been used to differentiate between methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) – two strains of bacteria that are difficult to distinguish using traditional methods [13]. By analyzing the electrical properties of the bacteria, CE can provide a rapid and accurate diagnosis, potentially saving lives in clinical settings.

2. Food Safety: Electrokinetic methods are also being applied in the food industry, where they can be used to detect the presence of harmful microorganisms in food products. For example, DEP has been used to identify E. coli in ground beef [14]. The ability to quickly and accurately detect pathogens in food is essential for preventing foodborne illnesses and ensuring public safety.

3. Environmental Monitoring: In environmental science, electrokinetic methods are being used to monitor microbial contamination in water. Insulator-based EK systems, for example, can detect the presence of microorganisms from large volumes of water, making them ideal for detecting low levels of contaminants in environmental samples [15,16]. This has important implications for public health, particularly in regions where clean water is scarce.

4. Phage Therapy and Viral Analysis: In addition to bacterial cells, electrokinetic methods have been used to study viruses. For example, bacteriophages – viruses that infect bacteria – have been analyzed and separated using these techniques. This has potential applications in phage therapy, an emerging treatment for antibiotic-resistant infections [17]. By separating and characterizing different types of phages, researchers can develop more targeted therapies to combat antibiotic-resistant resistant bacteria.

Future Directions

This article concludes by discussing the future potential of electrokinetic methods in microbiological research and clinical applications. As the technology continues to evolve, there is hope that these techniques will become more widely adopted in clinical laboratories. The miniaturization of EK platforms, in particular, offers exciting possibilities for developing portable diagnostic devices that could be used in resource-limited settings.

Furthermore, the ability to analyze microorganisms without the need for culturing is a game-changer. Traditional methods for identifying pathogens often rely on growing the organisms in a lab, which can take days. In contrast, electrokinetic methods can provide results in minutes, offering a faster and more efficient alternative.

Conclusions

Electrokinetic-based methods represent a significant advancement in the analysis and separation of microorganisms and nano-sized particles such as viruses. By exploiting the electrical properties of cells and viruses, these techniques offer a faster, more accurate, and more efficient alternative to traditional methods. Whether it’s diagnosing infections, ensuring food safety, or monitoring environmental contamination, electrokinetic methods are poised to revolutionize a wide range of fields. As research in this area continues to advance, we can expect to see even more innovative applications of this exciting technology.

References:

[1] Hakim, K. S., Lapizco-Encinas, B. H. Electrophoresis 2021, 42, 588–604.

[2] Vaghef-Koodehi, A., Lapizco-Encinas, B. H. Electrophoresis 2022, 43, 263–287.

[3] Polaczyk, A. L., Amburgey, J. E., Alansari, A., Poler, J. C., Propato, M., Hill, V. R. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2020, 586, 124097.

[4] Crispo, F., Capece, A., Guerrieri, A., Romano, P. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 68, 506–513.

[5] Horká, M., Šlais, K., Šalplachta, J., Růžička, F. Anal. Chim. Acta 2017, 990, 185–193.

[6] Horká, M., Štveráková, D., Šalplachta, J., Šlais, K., Šiborová, M., Růžička, F., Pantůček, R. J. Chromatogr. A 2018, 1570, 155–163.

[7] Horká, M., Šalplachta, J., Karásek, P., Růžička, F., Štveráková, D., Pantůček, R., Roth, M. ACS Infect. Dis. 2020, 6, 2745–2755.

[8] Su, Y. H., Rohani, A., Warren, C. A., Swami, N. S. ACS Infect. Dis. 2016, 2, 544–551.

[9] Han, C. H., Woo, S. Y., Bhardwaj, J., Sharma, A., Jang, J. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–10.

[10] Vaghef-Koodehi, A., Ernst, O. D., Lapizco-Encinas, B. H. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 1409–1418.

[11] Kasarabada, V., Nasir Ahamed, N. N., Vaghef-Koodehi, A., Martinez, G., Lapizco‐Encinas, B. H., Nihaar, N., Ahamed, N., Vaghef-Koodehi, A., Martinez-Martinez, G., Lapizco-Encinas, B. H. Anal. Chem. 2024, in press.

[12] Vaghef-Koodehi, A., Dillis, C., Lapizco-Encinas, B. H. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 6451–6456.

[13] Horká, M., Tesařová, M., Karásek, P., Růžička, F., Holá, V., Sittová, M., Roth, M. Anal. Chim. Acta 2015, 868, 67–72.

[14] Choi, W., Min, Y. W., Lee, K. Y., Jun, S., Lee, H. G. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 132, 109230.

[15] Jun, S., Chun, C., Ho, K., Li, Y. Water (Switzerland) 2021, 13, 1678.

[16] Nakidde, D., Zellner, P., Alemi, M. M., Shake, T., Hosseini, Y., Riquelme, M. V., Pruden, A., Agah, M. Biomicrofluidics 2015, 9, 14125.

[17] Hill, N., De Peña, A. C., Miller, A., Lapizco-Encinas, B. H. Electrophoresis 2021, 42, 2474–2482.