Alumni are conduits of life-saving donations

Alumni are conduits of life-saving donations

A. Sue Weisler

Julie Burkett ’11 wraps an eye in gauze for easy handling.

Mark Lohkamp Jr. greeted the donor’s body with silent respect before getting to work. He located the saphenous vein that snaked up the body’s leg from foot to groin and edged a swath of tissue around the long blood vessel. He removed the muscle protecting the vein and packaged it for processing at a nearby tissue bank. Another set of technicians would lift the vein from the muscle like a delicate thread and prepare it for use in someone else’s body.

“Knowing that you can keep giving after you pass away is pretty rewarding,” says Lohkamp ’11 (biomedical sciences), Tissue Recovery Specialist III at the Rochester/Finger Lakes Eye & Tissue Bank.

The value of a blood vessel, a cornea, a tendon, or a heart valve lies in its use—a simple truth intrinsically understood by individuals who pledge to donate their organs, eyes or tissues when they die. Helping a stranger to see, walk—even breathe—after one’s own death is a powerful concept that resonates with Lohkamp and the other RIT alumni who work at the Rochester/Finger Lakes Eye & Tissue Bank. They are conduits of these peculiar posthumous gifts.

“It is a humbling experience, working with eye/tissue donors, and being able to help fulfill their wishes is something special,” says Nicholas Biondi, a senior in the biomedical science program in RIT’s new College of Health Sciences and Technology. “We are put in a unique position to be able to do our part to help them. It also provides me with great experiences.”

The bank

The Rochester/Finger Lakes Eye & Tissue Bank, which is an accredited member of the Eye Bank Association of America, serves 31 hospitals and health care facilities in the Finger Lakes, Southern Tier, central and northern New York regions as well as north central Pennsylvania.

The organization recovers, processes, preserves and distributes corneas and other tissue for transplant and research, says communications director Karen Guarino ’97 (public relations certificate program). Partnering organizations process other recovered tissue.

“We also fund local transplant-related research projects, educate the public about the needs for and benefits of donation, and provide education for health care professionals involved in the donation process.”

The agency averages 300 calls a month. “We have to cover 24/7, 365 days a year so we have to make sure we have enough staff,” Guarino says. “You can’t anticipate when we’re going to be having a donor.”

RIT alumni and current students comprise nearly 40 percent of the entire staff of 12 full-time and 14 per-diem people. Seven of the 14 eye bank technicians and tissue recovery specialists, in particular, have RIT connections.

Guarino and education coordinator Patricia Moorehouse ’81 (career and human resources) also contribute to the organization’s communication and educational outreach.

Many of the recovery specialists at the eye and tissue bank knew Lohkamp from gross anatomy at RIT. The upper-level science class teaches students to relax in the presence of cadavers and to dissect upper extremities, backs and abdomens.

Julie Burkett ’11 (biomedical sciences) and Sarah Taber ’11 (biomedical sciences) were lab partners with Lohkamp.

“He talked about his job. I liked gross anatomy so I figured I would like the job and that it would be a great opportunity,” Burkett says. “Sometimes it’s exhausting, but it’s good. It’s rewarding. It’s interesting. Every case is different, so you learn a lot about medicine and diseases.”

Taber says she has learned how to do chart reviews, talk to nurses about medical histories and how illnesses affect the body.

“On my cases, I get to see what drugs were administered and what effect they had or what medical measures were taken to preserve each person’s life,” she says. “I learn something new on every case about the human body and the way it functions.”

Burkett and Taber followed Lohkamp’s path to the eye and tissue bank, taking per diem shifts as eye technicians in September.

“Ten weeks of gross anatomy broke it in for me,” Burkett says. “Still, it’s like meeting someone for the first time. You have to get over that. Then you realize you know what you’re doing and you do it.”

The agency hired Lohkamp in March 2010, during his third year at RIT, and promoted him last October as a full-time tissue recovery specialist III. Lohkamp is the team leader on tissue cases and supervises and trains other technicians.

Last December, Lohkamp was sent to a partnering tissue agency in Baltimore to learn how to perform heart and blood vessel recovery, making him one of the most flexible and cross-trained specialists on staff next to the clinical director, Tammi Sharpe.

Bankers’ hours

Time works against the recovery specialist. “Ideally, corneas are recovered within 12 hours of a patient’s death,” Lohkamp says. “For other tissues we have up to 24 hours to recover.”

Recovered eyes and tissue have a shelf life: corneas, for instance, need to be transplanted within 14 days, Sharpe adds.

Burkett and Taber, who each average about 35 hours per week, supplement their per diem work as referral specialists. When hospital staff notifies the eye bank of a death, the referral specialists screen potential donors and check the New York State Donate Life Registry or call out of state as necessary.

“We’re the first in line, and then it continues after that,” Burkett says.

If the referral specialist determines the deceased is suitable for eye and/or tissue donation, then Sharpe or another tissue bank coordinator contacts the next of kin to offer the option for donation, or in the case where the deceased is enrolled in the state’s consent registry, to explain the donation process.

The recovery specialists have an hour to get to the office when the coordinator calls with a case. Eye specialists, who work individually, grab their pre-made kits—“a cooler on wheels,” containing gowns, gloves, eye kit and disposable instruments, Lohkamp says. The tissue team, usually three to five specialists, meets at the office or at a local hospital, depending on how far they need to travel.

“For out-of-town donors, we have a driver who comes to pick us up,” Lohkamp says. “Cases in Ogdensburg, for example, are a four-hour drive, and tissue recovery takes anywhere from six to 12 hours to perform, and then you have a four-hour drive back.”

Fatigue factors into the long shifts in a profession that demands perfection: fine-motor skills, hours of standing and extreme care to maintain a sterile field during recovery. Tissue recovery requires operating-room training—gowning, gloving and surgical scrubbing.

“We have to work through the night fairly frequently, and in order to perform the task at hand you need to stay sharp,” says Biondi. “There is no margin for error.”

Individual technicians are dispatched on eye donation cases once cleared to work solo. After reviewing the donor’s medical charts and assessing the body, the technician surgically removes the corneas or the whole eye if the scleras—the whites of the eye—are requested. The specialist returns to the office to process the ocular tissue in the laboratory.

Corneas look like soft contact lenses. Eye technicians take care not to stretch or rip the delicate tissue that could restore vision and prevent blindness in another person. Less frequently, surgeons request sclera to reinforce the wall of the eye for patients with glaucoma.

“Prior to working here, I didn’t even know you could receive corneal transplants,” Burkett says. “I like that every case is different. You go through the charts and you learn about people. It’s sad why you’re learning about them, but you see the whole process through to donation. We’ll even drop off corneas for surgeries as part of our jobs. It’s a great gift to give people.”

Specialists gravitate toward eye or tissue recovery for different reasons. Taber, who is cross-trained for tissue recovery, first trained as an eye bank technician, thinking the more common donation would yield more hours.

“I actually prefer eye donation over tissue donation because it is only me that goes on the case instead of a team of four. I have to do the chart review myself, which gives me a better sense of the patient’s background and what led them to the hospital.”

Biondi likes the group dynamics of working in a team focusing on collecting bone and tissue.

“I prefer group-based activities to individual tasks, so that weighed heavily on my decision,” Biondi says. “Also, since I had already taken gross anatomy, I was more familiar with the layout of tissues and tendons.”

Helping others

Many of the recovery technicians aspire to go to medical school. Lohkamp is interested in orthopedics. “Doing the tissue recovery is applicable to what I want to do, considering the surgeons use a lot of the tendons we recover.”

Taber will begin osteopathic medical school at Virginia Tech this fall with hopes of becoming a pediatric cardiologist.

Like Taber, Biondi and Burkett also express interest in pediatrics and are interviewing at prospective medical schools.

“A lot of per diems use this job as a stepping stone to further their careers or their future education goals, such as going to nursing school, physician assistant school or becoming a medical doctor,” says clinical director Sharpe. “There are other people who have made it a career; I started off as a per diem, just on weekends.”

A significant number of people benefit from recovered eyes and tissues, Sharpe says. “It will surprise you.” She pulls numbers from the agency’s annual reports from 2008-2010: 874 people received corneas, 106 were given heart valves, 45 recipients benefited from blood vessels and 650 were given skin grafts, while 6,790 individuals received bone, pericardium, fascia and tendons.

“First priority for these donor gifts of corneas and tissues is given to our local surgeons and hospitals,” Sharpe says. “If there is no immediate local need, only then are these gifts offered out beyond the Rochester region, out of state and then internationally. One eye donor can help two to four people. One eye, tissue and bone donor can help up to 75 people.”

The benefit extends to the staff at the Rochester/Finger Lakes Eye & Tissue Bank whose efforts make the donations possible. The nature of their work reflects back upon them.

“The best part of my job is knowing that I am actively making someone’s life better,” Taber says. “This experience has immersed me in the medical field and taught me that even after a patient has passed, they can still offer their help to others in need.”

Becoming a donor

People of all ages and medical histories are potential donors. The medical condition of the donor at the time of death will determine what organs and tissue can be donated. To learn more or to enroll in the New York State Donate Life Registry, go to www.donatelifenewyork.com. For information outside of New York, visit your state’s department of health website.

A cornea rimmed with sclera, the white of the eye, is packaged and ready for transplant. A. Sue Weisler

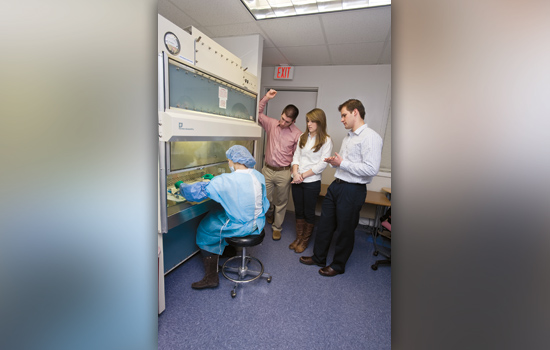

A cornea rimmed with sclera, the white of the eye, is packaged and ready for transplant. A. Sue Weisler Julie Burkett ’11, left, dissects an eye during a training session as RIT student Nicholas Biondi, Sarah Taber ’11 and Mark Lohkamp Jr. ’11 look on. RIT alumni and current students make up nearly 40 percent of the staff at Rochester/Finger Lakes Eye & Tissue Bank. A. Sue Weisler

Julie Burkett ’11, left, dissects an eye during a training session as RIT student Nicholas Biondi, Sarah Taber ’11 and Mark Lohkamp Jr. ’11 look on. RIT alumni and current students make up nearly 40 percent of the staff at Rochester/Finger Lakes Eye & Tissue Bank. A. Sue Weisler Julie Burkett ’11 prepares to process ocular tissue. A. Sue Weisler

Julie Burkett ’11 prepares to process ocular tissue. A. Sue Weisler