Professor recognized for role as a Pixar pioneer

Zelig Goodman-Hoffman '24

Flip Phillips introduces students to the world of virtual production — a technology that harnesses the power of a giant LED screen housed in RIT’s MAGIC Spell Studios — in a two-semester course he teaches. Phillips was recently honored for his groundbreaking, early-career work at Pixar.

It all started in a nondescript building tucked in an industrial park.

Flip Phillips, from his office in the early home of Pixar Animation Studios, sometimes had a front-row seat to the filming of scenes in the likes of Ghostbusters and Indiana Jones. In those moments, he could envision a future where the technology he was helping to build would gain prevalence.

“It was amazing-looking stuff they were doing with practical effects, and we were doing computer graphics,” said Phillips, now a professor of motion picture science in RIT’s School of Film and Animation. “We knew we were going to be doing that later. The stuff they were doing, that would be computers at some point.”

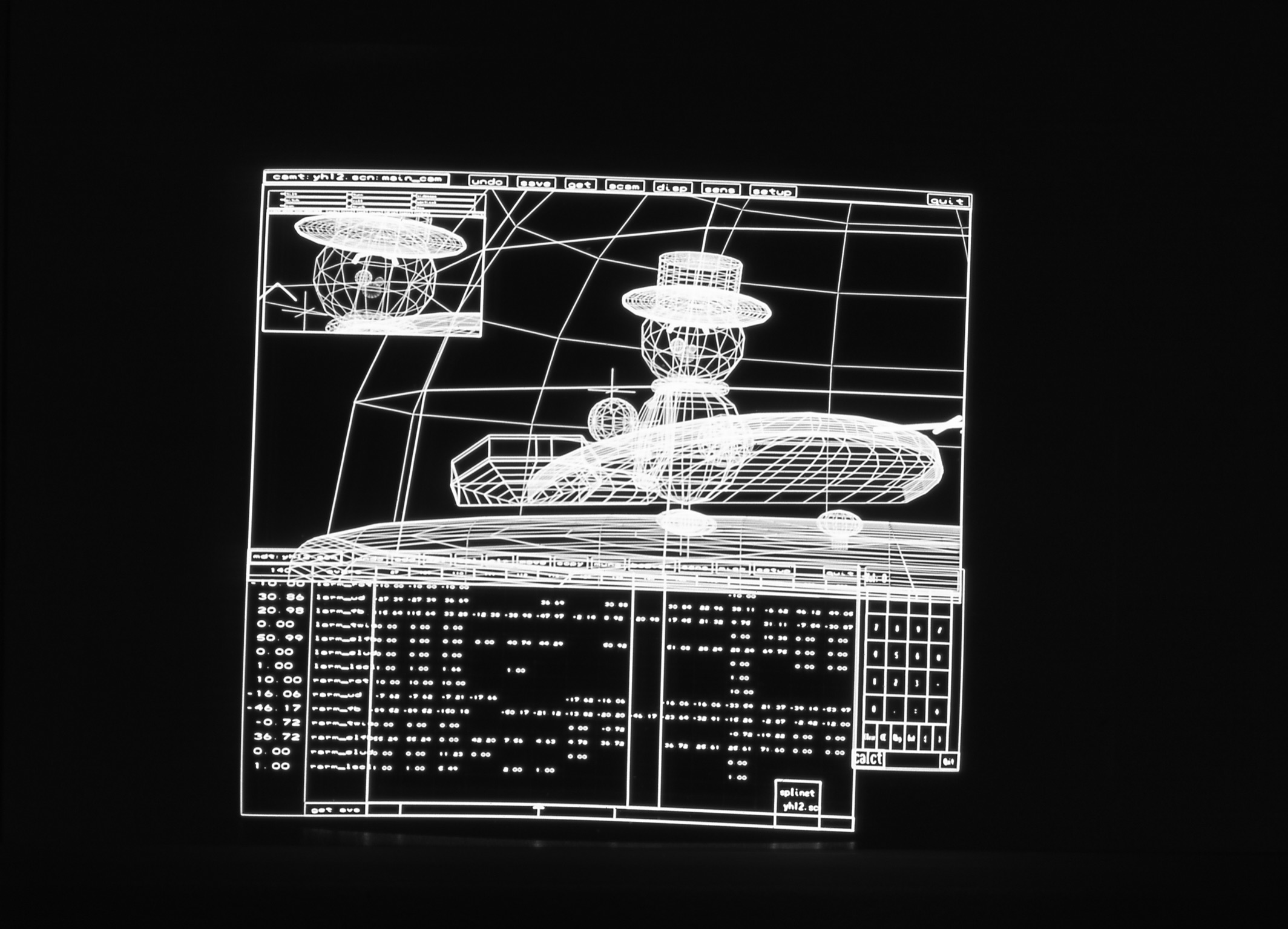

This “menv” system was used by Phillips and others to animate in their early days at Pixar. Pictured is the in-progress animation of a scene from the short film "Knick Knack."

From 1987-92, Phillips was an animation scientist at Pixar — "I was neither strictly an animator nor strictly a computer scientist,” he said. While there, Phillips was on the exclusive team charged with developing RenderMan, Pixar’s revolutionary 3D rendering software still used today to create the iconic animation look of classics such as Finding Nemo, Ratatouille, Toy Story and many others.

In December, the work of Phillips and former Pixar peers responsible for building the Hollywood-changing technology was bestowed a Milestone Award from the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), 34 years after the commercial release of RenderMan. The IEEE Milestones program recognizes significant technical achievements in engineering, computer science and related fields.

Phillips was in on the ground floor of a software handled by only a few, and subsequently enjoyed by millions.

“I’m one of hundreds to have touched this software, but I was able to do it in the beginning,” Phillips said.

Phillips was on the original animation team that helped launch RenderMan. He worked on its shading language, a computer graphics term describing the process to give rendered objects their color, intensity and other related properties.

The cover of “The Renderman Companion” manual that Phillips animated.

The cover of the software’s original manual, The Renderman Companion: A Programmer's Guide to Realistic Computer Graphics, featured a bowling ball crashing into pins. The scene was animated by Phillips using RenderMan to demonstrate how different materials could be brought to life in an efficient way not reliant on photography.

“The idea was rather than generating stuff photographically, we could generate it procedurally,” Phillips said. “So we can write a little bit of code that could execute fast compared to taking a picture.”

Phillips contributed to Pixar’s 1988 short film, the RenderMan-powered Tiny Toy, which became the first computer-animated film to win an Academy Award. He also made animated commercials for brands such as Listerine and Trident.

Pictured on the left are stills from “Tin Toy,” which won the 1989 Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film. On the right, Phillips holds the Oscar he had a hand in winning.

Phillips, known for his research centered on human perception of materials, 3D shape and motion through vision and touch, was hired by RIT in 2020 to teach in the motion picture science program. He was a central figure in establishing RIT’s virtual production curriculum.

Virtual production is a pioneering technique in film and media production blending filmmaking, computational photography and real-time game engine rendering to produce in-camera visual effects. It can create environments and effects more efficiently than other methods like green screen compositing.

Flip Phillips

RIT is among a small group in higher education to house virtual production technology and a companion curriculum. RIT partnered with Epic Games, THE THIRD FLOOR visualization studio and other Hollywood titans to construct a full research and learning ecosystem around the emerging workflows.

“Being in a place like RIT, you can learn the artistic parts of it and you can understand the physics behind it,” Phillips said.

Students in majors ranging from motion picture science, animation and production to imaging science to 3D digital design and new media design enroll in the two-semester Virtual Production class taught by Phillips. As a collection of different skill sets and ideas, the group explores the myriad capabilities of the technology, equipped with a massive LED wall stationed in MAGIC Spell Studios.

“Places like Pixar look not for people who are computer graphics experts — they look for people who have this integrative creativity,” Phillips said. “The point is to get them to work together and understand the constraints and explore the creative aspects of it.”

Elizabeth Lamark

In April 2023, Phillips facilitated a campus visit from Pete Docter, chief creative officer at Pixar Animation Studios pictured sitting on the stage, toward the left. Docter, the Oscar-winning director of “Monsters, Inc.”, “Inside Out” and “Up,” delivered a talk in MAGIC Spell Studios that was moderated by Phillips, pictured in the middle on Docter's left. The two are longtime friends.

Phillips is currently the principal investigator of a National Science Foundation-funded grant researching human perception of three-dimensional shape and material properties. Phillips and a group of motion picture science and imaging science students are exploring the idea that less can be more when it comes to 3D.

“What we’re trying to build our renderers to do is understand that humans don’t need a photorealistic reproduction of the world to see it,” Phillips said. “You can get by with a lot less. Perceptually there is only so much you need in order to understand.”