Big Goals, Tiny Chips

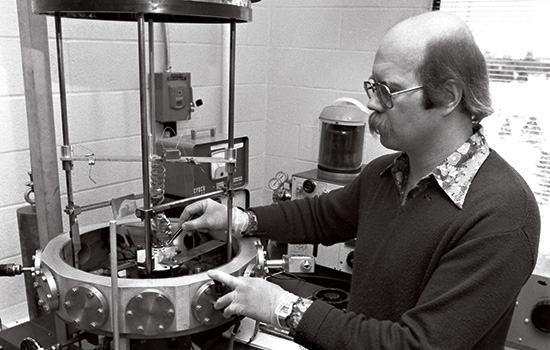

Lynn Fuller, pictured in 1981, says the field of microelectronic engineering has changed dramatically since he first started teaching.

Professor educates generations of microelectronic engineers

When John Robertson showed up as a transfer student at RIT in the summer of 1976, his very first class, Circuits I, was with Lynn Fuller.

“He was one of my favorite instructors and he had a unique ability to make complex concepts seem simple,” says Robertson, who had two more classes with Fuller before graduating in 1979 with his electrical engineering degree.

That’s why Robertson was excited when he learned his daughter, Olivia, was enrolled in Fuller’s Electronics II course last school year. “If he has been even half as influential on Olivia as me, she will be well prepared for an engineering profession—and life.”

Fuller ’70 (electrical engineering) started teaching at RIT 45 years ago as a teaching assistant before joining the College of Continuing Education two years later instructing night school classes. He did that for five years while getting his master’s degree and Ph.D. and then became a faculty member in the College of Engineering in 1975.

He says he tried working in industry on a co-op but quickly realized that it wasn’t for him. He was drawn to teaching because he is constantly learning.

The founder of RIT’s microelectronic engineering program (he helped launch the first-in-the-nation program in 1982) and former department head says the field has changed dramatically since he first started teaching.

“I remember when RIT got its first transistor,” he says. “Now we have cell phones with billions and billions of transistors in them.”

Fuller oversaw the construction of the department’s Semiconductor and Microsystems Fabrication Laboratory and continues to teach multiple labs where students get hands-on training. He also has a full load of courses at all levels.

When he isn’t teaching, he makes time for microsystems research. He has designed, fabricated and tested hundreds of different microchips. In May, he was inducted into RIT’s Innovation Hall of Fame.

Fuller, who was a four-sport athlete as an undergraduate in track and field, ice hockey, football and wrestling, has no plans to slow down.

There’s still more to learn—his goal is to make a sensor, now the size of a penny, the size of letters on a penny.

And there’s a new generation of students to teach and then send off to graduate school or to work at companies making tiny chips for products such as mobile phones and medical equipment.

Robertson is now president of RoviSys, an engineering company based in a suburb of Cleveland with more than 260 engineers, developers and project managers. Olivia Robertson hopes to go into digital design or power management after she graduates in 2015.

“Teaching has always been a good career and I still haven’t learned everything so I’m still here,” Fuller says. “Pretty soon I will be teaching grandkids of my former students.”

Lynn Fuller ’70 works with graduate student Elena Cortes Garcia in the Semiconductor and Microsystems Fabrication Laboratory. Fuller started teaching at RIT 45 years ago and is the founder of RIT’s microelectronic engineering program.

A. Sue Weisler

Lynn Fuller ’70 works with graduate student Elena Cortes Garcia in the Semiconductor and Microsystems Fabrication Laboratory. Fuller started teaching at RIT 45 years ago and is the founder of RIT’s microelectronic engineering program.

A. Sue Weisler