Black ASL

NTID researcher helps preserve rich history of Black ASL

NTID researcher helps preserve rich history of

When David Player ’19 (sociology/anthropology) was a student at RIT’s National Technical Institute for the Deaf in 2015, he became fascinated with how race, identity, and language, specifically sign language, are tightly connected and influenced by geographic and social factors like governmental and educational policies.

Today, Player, a master’s degree candidate at the University of New Mexico, attributes his passion for sociolinguistics to his work alongside Joseph Hill, the NTID researcher who lit the spark within Player to develop his own unique research studying the sign language of New Mexican Deaf communities.

“People often feel proud of their language and their identity— and the same goes for the Deaf community,” said Player. “But there are some variations of American Sign Language that have received almost no attention, and we’re working hard to get those recognized.”

Alumnus David Player is developing sociolinguistics research based on his previous work at NTID.

Associate Professor Joseph Hill is making an impact by studying the linguistic and community aspects of Black American Sign Language.

For years, Hill, assistant dean of NTID Faculty Recruitment and Retention and an associate professor in the Department of ASL and Interpreting Education, has studied how the segregation of southern Black Deaf Americans, along with their history and culture, has impacted the linguistics of today’s Black Deaf youth. Hill hopes his research will continue to uncover and preserve Black American Sign Language.

“Just as there are differences among languages like English, Spanish, and Mandarin, there are significant differences among sign languages,” Hill said. “And many people don’t realize that Black American Sign Language is different than the American Sign Language that many white people use.”

Hill’s research begins with the state-sanctioned separation of Black Deaf students and white Deaf students who couldn’t interact and, subsequently, developed their own ways of communicating with each other. But, when Black Deaf students and white Deaf students merged and eventually became interwoven into the mainstream educational system, the fusion not only created language barriers between races, but the unique features of Black ASL started disappearing as young people lost touch with their ancestors’ and elder peers’ distinct use of Black sign, its dialect, and its nuances.

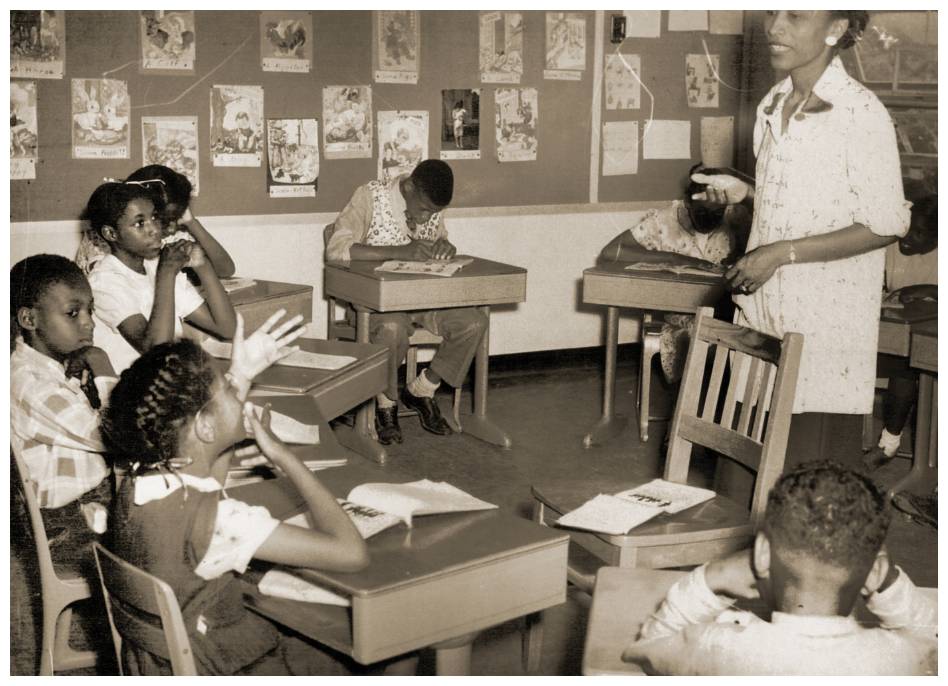

Black Deaf students learn together prior to the desegregation of Black and white schools.

Students board a bus bound for the Institute for Deaf, Dumb, and Blind Colored Youth, which was founded in 1887 in Austin. Today, the school is merged with the Texas School for the Deaf, a state-operated primary and secondary school for Deaf children.

Hill offers this example. In Louisiana, the older generation of Black ASL signers referred to the days of the week by counting down with their fingers. For example, five is for Monday, four is for Tuesday… to the closed fist for Saturday, and the praying hands for Sunday. However, the younger generation of Black Deaf signers instead uses the mainstream variety of ASL, in which the signs have an initial sign letter of each day, such as ‘M’ for Monday, ‘T’ for Tuesday, and ‘H’ for Thursday. The difference for Sunday is the open palm in a circular or downward movement.

Hill and his research team interviewed Black Deaf people in southern states, observing sign language, facial expressions, and movements.

“Black ASL is real—and often hidden—and needs to be uncovered, which is our purpose,” said Hill, who is also co-author of The Hidden Treasure of Black ASL: Its History and Structure, and one of the associate producers of “Signing Black in America,” the 14th documentary film in the Language and Life Project series, released by PBS in 2019.

“When I became involved in this research as a young Ph.D. student myself, I discovered that this area presented a rare opportunity to be transformative. It’s special.”

Hill isn’t the only one who thinks his work is special.

“Professor Hill’s research was eye-opening for me,” said Player. “His work with the Black ASL Project broadened my understanding of sociolinguistics in sign language, which is still not fully researched by sign language linguist scholars as much as it should be. I hope I can do the same for New Mexican Deaf communities as he did for those of us living in Black Deaf communities.”

Ceil Lucas, professor emerita of linguistics at Gallaudet University, and a Black ASL project leader, was Hill’s mentor on the Black ASL project.

“During our time working together and, even since then, Joseph has continually challenged me and has further underscored the importance of this research. His understanding and, more importantly, his desire to capture and preserve a lost language is both noteworthy and inspirational.”

Hill hopes he and others like Lucas and Player can be advocates for Black Deaf communities everywhere.

“My goal was to tell the stories of Black Deaf Americans and their rich history and culture,” Hill said. “Black Deaf people should be proud of their identity, their experiences, and their language. This is about resiliency through generations.”