RIT Press publishes new title in its Arts and Crafts Movement series

Chicago’s Atlan Ceramic Art Club elevated decorative arts and feminism

RIT Press

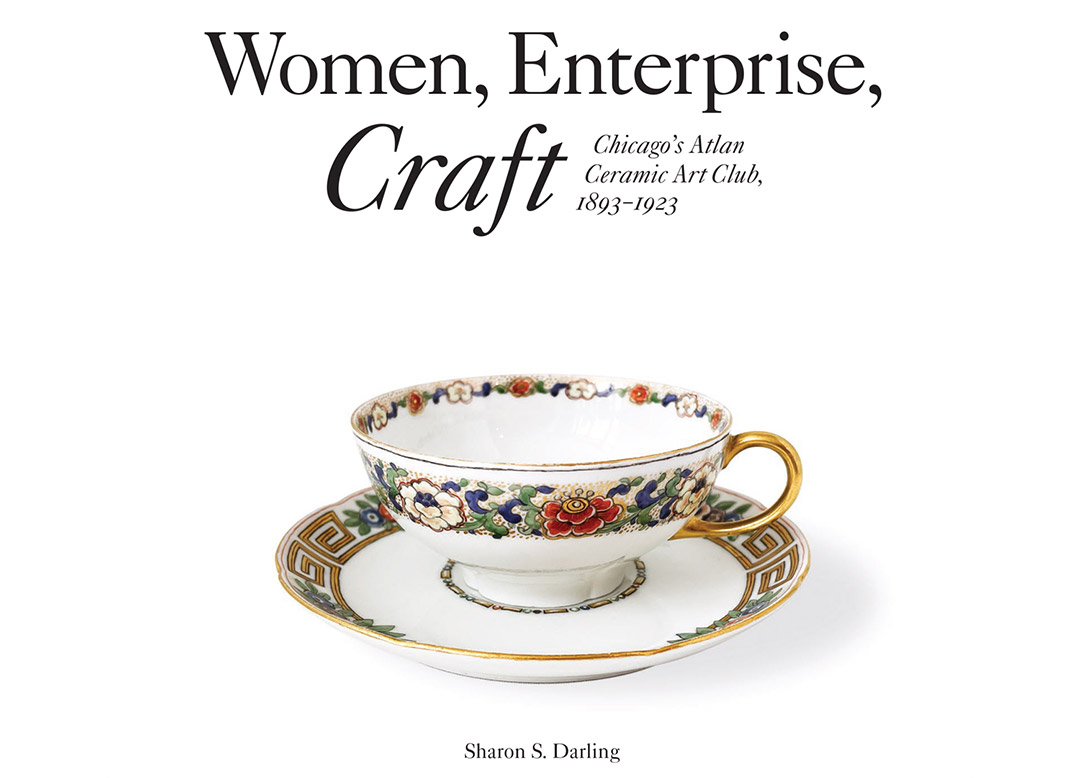

Women, Enterprise, Craft: Chicago’s Atlan Ceramic Art Club, 1893–1923, by Sharon S. Darling, revisits a studio of women china painters.

A group of women artists in early 20th century Chicago exemplified the connection between the decorative arts and feminist movements in the United States and is the focus of a new book published by RIT Press.

Women, Enterprise, Craft: Chicago’s Atlan Ceramic Art Club, 1893–1923, written by Sharon S. Darling, revisits the Atlan Ceramic Art Club, one of the leading studios of hand-painted china, or “china painting,” in the Midwest. The publication is part of the RIT Press Arts and Crafts Movement Series.

RIT Press

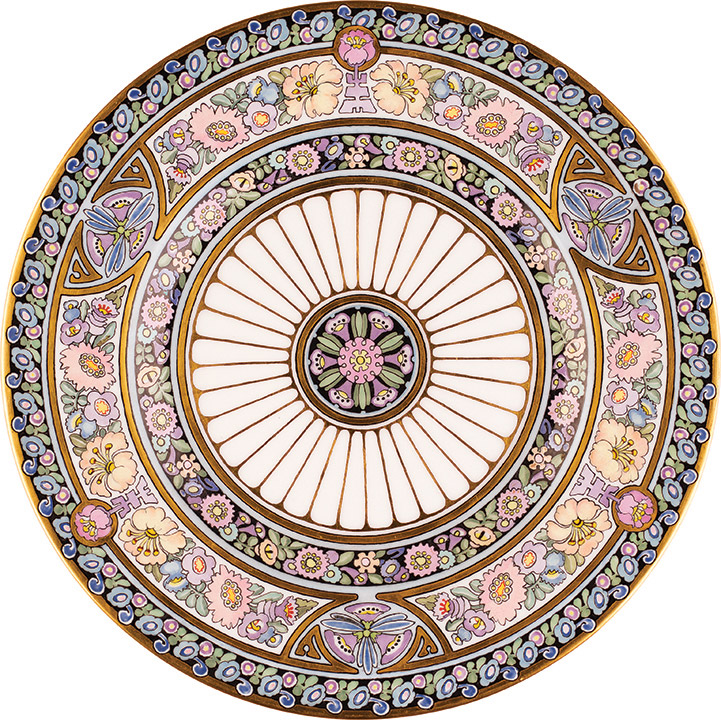

Atlan ceramic plate by Helen Frazee.

The Arts and Crafts Movement, popular from 1875 to 1920, inspired an appreciation for craftwork, simplicity, and natural motifs, and influenced the Chicago-based Atlan Ceramic Art Club.

Popular interest in ceramics spread across the country after the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial showcased decorated ceramics from France, Great Britain, and the Far East. Chicago was the Midwestern center for decorative ceramics when the Atlan club formed.

Fifteen women artists organized the elite professional association and exhibited as a group at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. The Atlan club lasted for 30 years and grew to include a younger generation of women with different nationalities, socioeconomic backgrounds, and religious affiliations, all adhering to a “conventional” style favoring abstract flowers and natural motifs painted over geometric shapes and exotic designs.

“Despite the club’s lengthy history, few collectors and curators have heard of the Atlan Ceramic Art Club or acknowledge porcelain decorated overglaze in the abstract ‘conventional’ style, as a significant part of the Arts and Crafts movement,” Darling wrote.

RIT Press

Atlan chocolate pot by Helga Peterson.

Atlan artists exhibited and sold their work over 30 years at annual shows at the Art Institute of Chicago. Today, only a few examples remain of the hundreds of plates, bowls, pitchers, tea sets, powder boxes, trays, and vases produced in this style. These objects were both beautiful and utilitarian, and many of them did not survive daily use. Works signed with the initials of their motto (“Patience, Persistence, Progress”) over the word “Atlan” are rare, according to the author. The Chicago History Museum houses the only major collection of Atlan china in the United States, she said.

The Atlan artists sought unsuccessfully to establish an original style of china painting that would outlast their era. Instead, they introduced a new way of imagining decorative ceramics, according to Darling. They “succeeded in establishing the style and its appropriateness on ceramic forms as a new art medium for the American Arts and Crafts movement.”

The Arts and Crafts movement paralleled the emerging feminist movement’s focus on individual talent and self-reliance. China painting was respectable work for women who needed an income. It also trained women to run a business and advance their artistic careers.

“For many women, china painting provided the artistic and management skills needed to become successful ceramists and businesswomen; for others, it was a bridge to work as interior decorators in the 1920s and 1930s, when European-influenced modernism prevailed, or to participate in the studio ceramics movement in America in the early 1940s,” Darling wrote.

Women, Enterprise, Craft: Chicago’s Atlan Ceramic Art Club, 1893–1923, by Sharon S. Darling, is available in hardcover with 176 pages and 216 illustrations. To purchase a copy, visit RIT Press.