Exploring themes, motivations, and the influencing power of historic military propaganda

Selected pieces from Falotico’s father’s collection of World War I and II propaganda art are on display now at the University Gallery as part of the exhibit he curated for his museum studies capstone project.

Whether they belonged to people who were close to us or were collected by complete strangers, someone famous, or someone who lived a seemingly common life, collections and artifacts left behind offer an intimate window into the lives of people who have passed before us. They allow us to understand and know a person more deeply, even if our time with them was limited or we never knew them at all.

James Falotico, a fourth-year museum studies major and history minor, inherited such a collection. It belonged to his father,Chris Falotico, a professor at Drexel University who passed away when Faloticowas in elementary school. He had been an avid collector of World War I and II propaganda art and artifacts, and growing up, Falotico often heard stories of how his father was constantly drawn to art of this era, an affinity that amassed a collection of nearly 100 pieces.

“When I told my mom I wanted to change majors to museum studies, she said that if I did, she hoped I would do something with my dad’s collection,” said James. That hope became a reality this month.

The capstone project requirement of James’ major provided the perfect opportunity and resulted in the exhibit on display now through February 3 at the University Gallery, Selling War and Buying Patriotism: Propaganda, Posters, and Prose from WWI and WWII.

In reviewing the collection, Falotico noticed four common themes repeatedly emerging in the artwork: the protector theme in which soldiers are glorified; a sacrifice theme which commended the many small and big sacrifices people, on the front lines or homefront, were making for the war effort; the savior theme used by the American Red Cross, for example, with its idealized portrayals of brave, nurturing women; and the enemy theme with its dehumanizing and sinister imagery.

Each theme has its unique goal in influencing beliefs and rallying sentiment as the war moved on. Falotico carefully reviewed his father’s collection, piece by piece, looking for the best examples of each theme to include in the exhibition.

“I started with the themes and worked backwards from there,” he explained. “The distinction [in the themes] is how the art was used, what its goal was.”

Artwork in the exhibit is complemented by ephemera, journals, and other artifacts collected by Billie Wiren, who served with the American Red Cross during and after World War II.

Using skills he learned from research and coursework in multispectral imaging processes, Falotico imaged some of the posters from his father’s collection. He also interned in RIT’s imaging science-museum studies cultural heritage imaging lab, and in June 2023, he traveled to Oslo, Norway, for the Society for Imaging Science and Technology’s Archiving conference, at which he presented a paper co-authored with faculty and students in the lab. Now, as he finishes his last semester, Falotico has an eye on his next step in the field.

“I’d like to work for the National Gallery or in Washington, D.C., doing digitization of cultural heritage artifacts,” he said. “While I was in Oslo, I made a lot of connections, and I’m hoping some of those connections will lead to a job.”

Meanwhile, as James was sorting through his father’s collection, Kathy Hodges, of Webster, was sifting through a collection of war time materials, too—her mother’s letters, photographs, diaries, scrapbooks, and ephemera from her World War II era service with the American Red Cross.

For decades, Hodges and her brother dutifully protected more than 600 letters that their mother, Billie Wiren, had sent home. Hodges contacted Museum Studies Program Director Juilee Decker, in hopes of finding a way to preserve or digitize the collection, and Decker was eager to help.

Margo Clements

"Projects like this get to the heart of what our degree program is about. ‘Learning by doing’ is part of our DNA. Museum studies students apply concepts and methods that they have learned about in class leading to the creation of online and onsite exhibitions, for instance,” said Decker. “In this particular case, James built out the plan for this exhibit in consultation with faculty in the program. He curated his own collection of historic posters and paired those with Kathy's collection of personal items. Together, these materials help to tell a fuller story. Exhibitions like this one, and other multifaceted projects such as the Clarissa Uprooted exhibit (from 2022), enable us to offer opportunities for visitors to reflect on past and present and to come away with new knowledge about the topic presented."

During a time of comparatively limited occupational opportunities for women, Wiren served a total of six years in England, Germany, Korea, and Japan, and she contributed to the war effort and support of U.S. soldiers. She wrote reports to administration, made requests for supplies, endured hard winters in Korea, and was a kind friend to many soldiers until they could get back home.

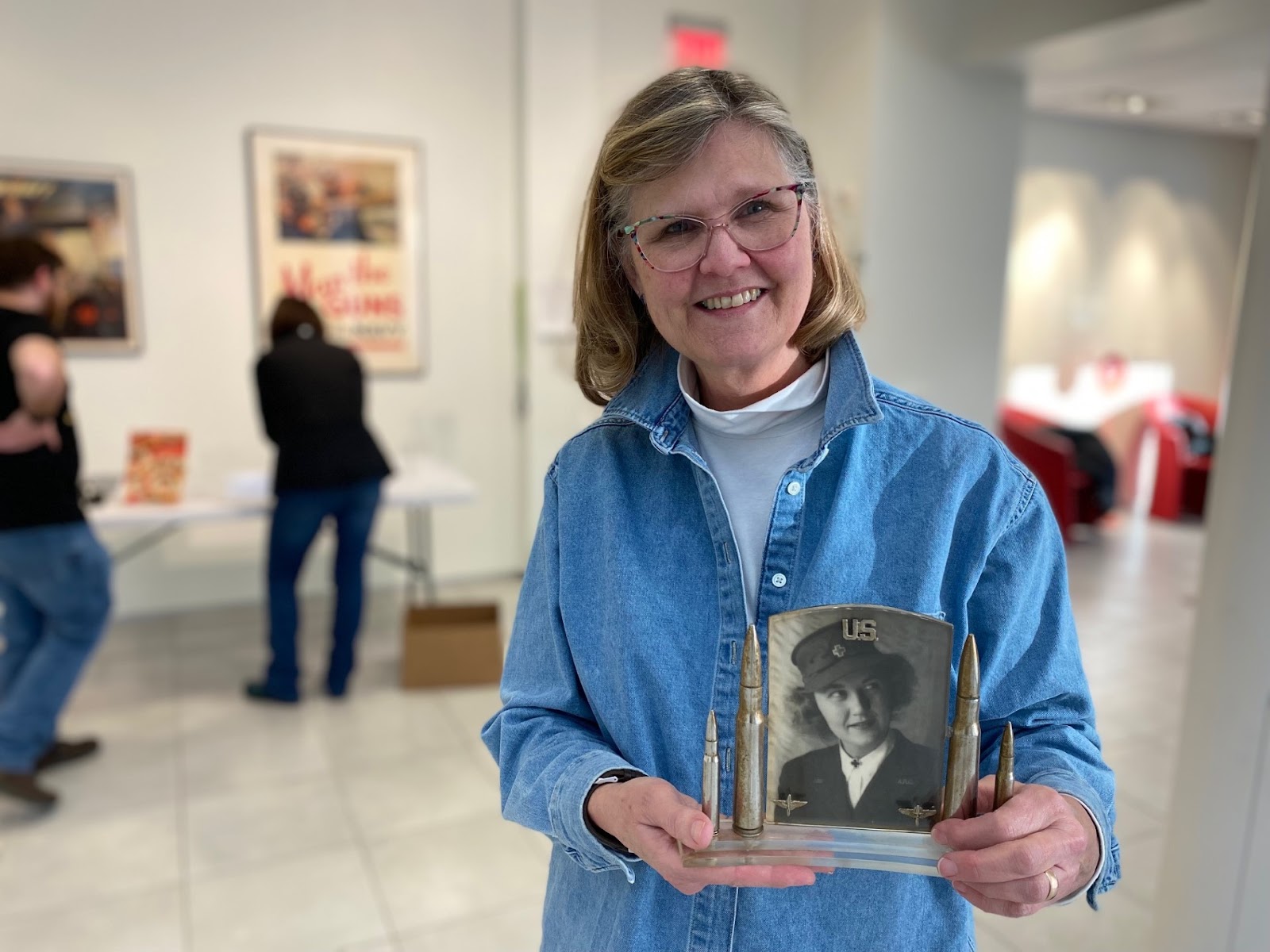

Kathy Hodges holds a photo of her mother, Billie Wiren, who sent more than 600 letters home while she served with the American Red Cross during and after World War II.

“She was a good writer. The detail in the descriptions of what she was experiencing as she was doing her job is remarkable,” said Hodges. “A lot of her job was about morale, keeping up the spirits of the soldiers. She refers to them as ‘the boys’ in her diaries and letters. She wrote that ‘the boys’ jokingly called her ‘the wheel’ because she always got things rolling.”

Letters she sent home, written for a small audience of parents and her closest family, offered accounts of her day to day life and descriptions of the beautiful landscapes she saw as she traveled. Her reports are brief and positive, partly due to wartime censorship that limited her in sharing information that might hint at where they were stationed.

“In her diaries, her entries were more open and sometimes she wrote things like, ‘visited with the boys today. It was rough'," said Hodges.

Wiren’s writings offer an authentic glimpse of life on the front lines during the war, what travel was like then, and the living conditions in the nations and places she was stationed. Her perspectives as one of the relatively few women near the front lines during this time make her accounts even more precious. In fact, plans are underway to transfer ownership of Wiren’s collection to the Library of Congress.

For now, several pieces collected by Wiren are on display alongside artwork from Falotico’s father’s collection. Selling War and Buying Patriotism: Propaganda, Posters, and Prose from WWI and WWII will be on display at the RIT University Gallery now through February 3. An opening reception will be held January 25, 4 to 6:30 p.m.