Like It Or Not, Generative Ai Is Changing Education

at RIT

like it or not, generative ai is changing education

Copy. Paste. Fourth-year cybersecurity student Tyler Spaulding puts his computer code into ChatGPT and asks, “Why am I getting an error?” Within seconds, the artificial intelligence (AI) chatbot generates an answer.

However, this RIT student isn’t using AI as a shortcut. As he studies the structure and syntax of his code, he jumps down a rabbit hole of problem solving—asking himself “why does this work and how?”

“At the end of the day, I see AI as an efficient tool for people who want to learn,” said Spaulding. “Yes, you could use AI to spit out a quick answer, but I use it to further my understanding of things.”

ChatGPT is just one of many generative AI tools that has taken the world by storm in the last year. The technology identifies patterns from existing data and quickly produces unique content that mimics human creativity. In addition to writing computer code, people can use AI to alter an image, compose a new song, and write a paper.

Like many fields, the world of academia is wrestling with the challenges and opportunities presented by generative AI tools. While a few K-12 school districts, international universities, and businesses have attempted to ban the use of AI tools, RIT is acknowledging that it’s here to stay and can be used as a force for good.

Today, hundreds of RIT researchers are developing a range of applications using AI, varying from medical monitoring devices to deepfake detection tools. RIT also started a master’s degree program in artificial intelligence this fall that aims to prepare well-rounded AI professionals from diverse educational backgrounds. Throughout the university, generative AI is redefining the boundaries of creation.

“Generative AI is already extensively used across our society—it has moved out of research labs and into our home and work environments,” said Cecilia Alm, professor in the Department of Psychology, School of Information affiliate faculty, and joint program director of the master’s in AI. “It’s changing how we work and live, just like other technology has done in the past.”

In the classroom, AI is forcing faculty members to change the way they teach. How can faculty embrace a new technology that graduates will likely use in their careers, while making sure students still learn the fundamentals of their discipline? It also raises issues with academic integrity and AI ethics.

Finding the right balance is key to preparing students like Spaulding, who need to understand how to effectively use AI in their future jobs.

“Faculty are preparing professionals who will use and develop this technology,” said Alm. “AI will continue to change and the approach to AI should be nuanced.”

‘Moral responsibility’

For 25 years, the final assignment in Neil Hair’s digital marketing class was a 20-page report. This year, the associate professor killed the term paper.

“Instead, I’m having students research and give a presentation that focuses in on all the nuts and bolts of the learning objectives in my course,” said Hair, recognizing that a student could use generative AI to write the paper for them in seconds. “AI tools are changing the game, and we as faculty need to evolve how we teach.”

Hair serves as executive director of RIT’s Center for Teaching and Learning and is helping lead the campus discussion about pedagogy and AI. When generative AI tools first hit the mainstream last fall, he remembers the uproar of concern from educators. However, at RIT, that panic quickly subsided and turned into a cycle of trepidation and excitement.

“RIT faculty are really creative and known for active learning in technology,” said Hair. “We have a moral responsibility to teach our community about AI, and I think RIT is in a good place to address these questions and embrace it.”

This fall, faculty members vary in how they’re using AI in the classroom. Some have instructed students to restrict AI use in certain cases, while others encourage students to articulate when and how they are using it. Faculty members have set up teaching circles to discuss AI in their disciplines, and several instructors are even using AI to refresh and refine their own lesson plans.

Liz Lawley, professor of interactive games and media, calls generative AI the most influential technology she has ever seen as a teacher—even more significant than the internet, due to the pace of change.

She has equipped the syllabi for her Introduction to Interactive Media and Introduction to Web Development courses with a statement about AI use, noting that although AI tools can be helpful, they can pose risks of inaccurate information and make it easy to avoid learning core concepts.

“Students are obviously going to use these tools, but how do we make sure they use them in a way that doesn’t prevent them from learning the building blocks we know they’re going to need moving forward?” said Lawley. “I want them to realize that you can’t do the really complex, sophisticated, and creative work if you don’t know how to do the basics.”

According to Lawley, if teachers tried to ban generative AI, it would be a losing arms race. She explained that while there are tools that claim to detect text generated by AI, they do a relatively poor job and have a problematic false positive rate when it comes to students for whom English is not their first language.

“Even if you could catch it, you can’t prove it,” said Lawley. “I want students to acknowledge when they use AI and tell me how they made it better, because that’s actually the skill I want students to learn—critical thinking.”

In Introduction to Interactive Media, Lawley’s students are using multiple generative AI tools for tasks ranging from drafting an outline for a persuasive argument essay to creating simple graphics for a website prototype. Each time, Lawley asks students to critically assess the materials created and consider the ethical issues related to these tools.

Lucy Zhang, a third-year computer science major, had a similar assignment in the spring 2023 semester. In a Chinese language course, her professor asked students to translate the lyrics of Chinese songs using ChatGPT—mistakes and all. Students then translated the songs back to Chinese themselves.

“The assignment actually showed the limitations of ChatGPT,” said Zhang, who is from Rochester, Mass.

Zhang said that she views AI as another tool, akin to Google. She has used AI to create websites in Python and to come up with funny team names for class projects. AI also came in handy when reviewing topics for finals.

For last spring’s Imagine RIT: Creativity and Innovation Festival, Zhang worked with Engineering House to create an AI mascot called Gearbo that could answer any question about the RIT special interest house.

“I think being able to efficiently use AI will be a powerful tool for engineers and other workers,” said Zhang. “AI is good at getting the ball rolling, but you still need human input. AI is not able to create innovation, but it can inspire it.”

Deep thinkers

Benjamin Banta, associate professor of political science, encourages his students to debate AI. In his Cyberwar, Robots, and the Future of Conflict course, he touches on removing the soldier from the battlefield and the decision-making process via drone warfare.

He poses the question, “What if an algorithm decides to kill someone?”

For Banta, it’s important that RIT approaches generative AI technology holistically, rather than from a position of assumed technological progress and optimism.

“I prompt students to ask whether we need it, why it’s being developed and promoted in certain areas, and how it ultimately should be utilized if we want to promote a thriving democratic society,” said Banta. In the classroom, Banta understands that some students will use generative AI as part of their research process. He encourages students to then go to the original sources and not to copy text from AI verbatim.

“RIT is on the forefront of technology, and it’s important that our students are deep thinkers,” said Banta. “When our graduates go out, invent the next big thing, and make a billion dollars, I also want them to be thinking about these issues. It’s important to be users of the technology—not used by the technology.”

Juan Noguera, assistant professor of design, has also thought about AI from the start. Last fall, he challenged his industrial design master’s students to see how they could use AI as part of their design process.

Noguera himself has used AI image generators to augment his ideation process. With a simple text prompt in DALL-E 2, users can get a flood of unique images.

He likens it to getting inspiration from reading a book or a trip to the museum.

“With my students, this project sparked amazing conversations about authorship, ethics, and the evolution of our design discipline, with students seeing parallels with the introduction of computer-aided design and the internet,” said Noguera.

For the project, industrial design master’s student Jayden Zhou sought to design a musical instrument. At first, he prompted the AI image generator Midjourney to create “futuristic sci-fi stringed instruments.”

In the end, he developed an electric violin with a fingerboard that illuminates as the instrument is played. Zhou wrote that he could see AI changing the process of creation, but not the essence of creation.

Other students in the class created assistive technologies, a chair inspired by fruit, and shoes made out of fungus. They all used AI in different ways, but noted how it led them down an unexpected path. Noguera was impressed.

“AI technology is not going away anytime soon,” said Noguera. “As educators and forever learners, I believe we have a responsibility to explore it.”

010AI and Alumni010

Prompting new images

Stan Kaady ’88 (photographic illustration) is pointing his lens in a new direction. In addition to photography, he’s now creating art using generative AI.

Midjourney is one of many AI programs that allows users to generate images from natural language descriptions, called prompts. Kaady’s journey into generative AI began with a free trial, which he eagerly explored and exhausted in just half an hour.

“It’s like learning image making all over again,” said Kaady, an advertising and editorial photographer based out of Atlanta.

Kaady is now filling his Instagram with AI creations. He’ll often develop a set of images to showcase the iteration process. One series depicts a fashion shoot of Barbie dresses that pay homage to Robert Oppenheimer, reflecting themes of atomic particles and nuclear reactions.

Sometimes he’ll experiment with prompts based on song titles, a book passage, or import a movie still or artwork that he finds interesting. Kaady recalls that he was trained to previsualize and post visualize images—a technique championed by Ansel Adams and other photographers. However, he finds there is no post visualization with the generative AI process.

“The parameters and features for Midjourney and other AI programs change quickly,” said Kaady. “With AI you are learning to harness the prompt objectives. I’ll try different color suggestions, lighting language, move the words around, put emphasis on words, and process the image even more in Photoshop.”

D Abandoned luncheonette: A prompt inspired by a Hall and Oates song.

AI for drug design

Generative AI and reinforcement learning is steering the design of life-saving drugs.

David Longo ’10 (computational mathematics) is CEO of Ordaōs, a machine-driven drug design company that creates biological molecules smaller than monoclonal antibodies, called mini-proteins.

“Five years ago, AI was a dirty word in the pharma industry, but now it’s shifted to this concept of intelligence in the process,” said Longo. “AI actually allows us to get far more hands-on and deterministic about our designs.”

Longo co-founded Ordaōs in 2019 with Steve Haber ’09 (information technology), the chief solutions architect. When starting the company, the team sought to rethink how AI could be used in every step of the design process—from sequencing problems to cell signaling.

Ordaōs is reinventing medical research by creating and evaluating billions of proteins via computer simulation, and then continuing to test and tweak those novel mini-proteins with generative AI. Ordaōs then rigorously synthesizes and tests the top-ranking sequences in vitro.

Mini-proteins designed by Ordaōs provide the power and performance of antibodies but are more configurable, stable, and easier to manufacture. While the mini-proteins are disease agnostic, a lot of the company’s work is currently in oncology, leading to cancer drugs.

The company is now part of the AWS Generative AI Accelerator.

Give AI the repetitive tasks

Sometimes AI seems to read minds. That’s how Edmond Behaeghel ’22 (computing and information technologies) feels when he’s using GitHub Copilot, an AI pair programmer.

Copilot acts as an advanced autocomplete for coding. The generative AI works with a programmer’s integrated Fdevelopment environment—such as Visual Studio—to suggest code. Whether Behaeghel is using the AI for a personal project or to develop IT solutions as a controls engineer at Barry-Wehmiller Design Group, he finds it helpful.

“It’s really good at handling repetitive and boring tasks,” said Behaeghel, who works from Geneseo, N.Y. “If you are creating a calendar and you have to type the same thing 12 different times, it can do that for you. But you still have to understand how the code works to develop software.”

Behaeghel has also used the tool to create outlines, set up databases, work on conditional statements, or send dynamic data to other users.

He said that he’s careful to only use it for hypotheticals in a sanitary environment, before adapting the software for real use.

“It’s a helpful tool, but it’s not a night-and-day transformation in being more efficient,” Behaeghel said. “It just sets me up real quick, so I can spend more time working with the data.”

Creative responsibility

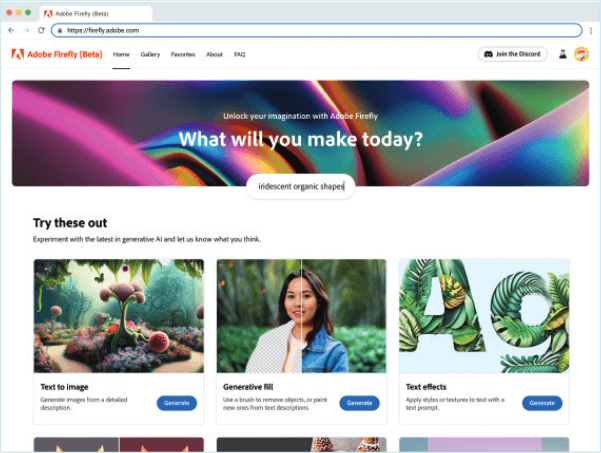

Kelly Hurlburt ’17 (new media design) is a lead designer of Firefly, Adobe’s new generative AI tool for its Creative Cloud software. She’s also making sure it’s deployed responsibly.

With Firefly, people can use simple text prompts in more than 100 languages to make images. Users can easily generate images, remove objects or paint in new ones, apply styles or textures, generate color variations, and extend images.

As a senior staff experience designer at Adobe, Hurlburt is extensively involved with the overall strategy and design of the tool. She said Firefly invites more people into a creative space that is inaccessible to many.

In developing Firefly, the design team considered concerns from the creative community. The team trained the software to only use Adobe Stock and public domain images out of copyright. She also cited a committed focus to integrating AI into the existing workflows to expand, not replace, the role of creatives and applying measures to increase transparency and reduce bias of the AI model.

“I care deeply about art and my fellow creatives, so I feel grateful to be in a position where I can tangibly influence the technology in a positive direction,” Hurlburt said.

Smarter communications

Stacy Lake ’05 (marketing), ’07 (MBA) is leaning into generative AI to streamline the language process.

As corporate communications manager for Salas O’Brien, an engineering and technology services firm with offices across North America, Lake is finding ways that AI can help her clients and her team. Her communications team is leveraging the AI writing tools ChatGPT and Jasper to create and refine content.

“For example, we develop a lot of case studies and we sift through countless input to create them,” said Lake, who works from Sarasota, Fla. “Now, we can jumpstart that process by dropping the input into a writing tool with pre-built parameters and templates that match our specific tone and language requirements.”

The team also used AI tools to trim down long requisitions into short, 150-word versions and to create LinkedIn post ideas for their engineers during the latest brand rollout.

Lake said the company has a policy regarding the smart use of these AI tools. The technology cannot be used where there is any possible liability or confidential information.

“I don’t see AI replacing communications jobs, but I do want future communications graduates to have the skills to leverage and use these tools,” said Lake. “AI is only as good as the prompt you put into it.”