Growing Diversity

Growing

Diversity

Faculty recruitment program, new strategies aim to improve representation

While tending to corn crops in a small plot of land on the south end of campus, Assistant Professor Eli Borrego is pushing RIT into new territory. As he pollinates maize lines with broken genes, he is laying the foundation for years of research studying hormones and their roles in agriculturally important processes.

Borrego is an expert in the genetics and biochemistry of plant-microbe and plant–insect communication and ecology. RIT recruited him to help the university expand into new areas of research related to genomics and agriculture.

“I think there’s nothing more important than helping to feed the world,” Borrego said. “We also need to show people, especially the next generation, that agriculture is more than just crops and cows. For students who are interested in molecular biology and biochemistry, you can use sophisticated approaches—genomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics, and lipidomics—on agricultural crops.”

Borrego might not have come to RIT without the Future Faculty Career Exploration Program (FFCEP). FFCEP is a rigorous four-day program designed for African American, Latino American, and Native American (AALANA) scholars and artists to experience a behind-the-scenes glimpse into life as a faculty member at RIT.

Each year, 20 to 25 participants spend time learning from and networking with RIT administration, faculty, and students, practicing interview skills, and research presentations while exploring the research, teaching, and service expectations of RIT faculty.

Borrego was an assistant research scientist at Texas A&M University when he participated in FFCEP in 2018. He said one of the most important people he met was Professor André Hudson, head of RIT’s Thomas H. Gosnell School of Life Sciences.

Action Plan for Race and Diversity

The plan will guide RIT’s efforts over the next several years as it rolls out new programs, services, and policies to help create equal access, opportunities, and respect for all students, faculty, and staff. One of the plan’s three key pillars focuses on faculty and staff recruitment, retention, and advancement. Some of its strategies include bolstering personnel and funding support for the Office of Faculty Diversity and Recruitment, requiring inclusive hiring training for people on search committees, and building new relationships with historically Black colleges and universities, Hispanic serving institutions, and Native American scholars initiative universities.

It was a chance for Borrego to showcase his expertise and for Hudson to explain the university’s emerging research interests. The relationship they established helped lead to Borrego joining the College of Science in 2019.

“André’s been a great mentor and influence,” Borrego said. “He recognizes that my program is a long-term investment. And actually, I was kind of terrified about living in the north because of the cold and snow. But he said, ‘I’m from Jamaica. If I can make it here, anyone can.’”

Keith Jenkins, RIT’s vice president and associate provost for Diversity and Inclusion, said that intentional efforts like these to help attract diverse scholars are crucial to the university reaching its potential.

“Fundamentally, what research has shown is that diverse work teams are more creative, innovative, and generate greater ideas and outcomes than those that are less diverse,” Jenkins said. “Our strength rests in our diversity. Whether as a department, as a college, as a university, or as a society, there is no way to get around it. We need it.”

Minett Professorship

celebrates 30th year

A long-running program that brings distinguished Rochester-area multicultural professionals to share their knowledge and experience with the RIT community reached a major milestone this year.

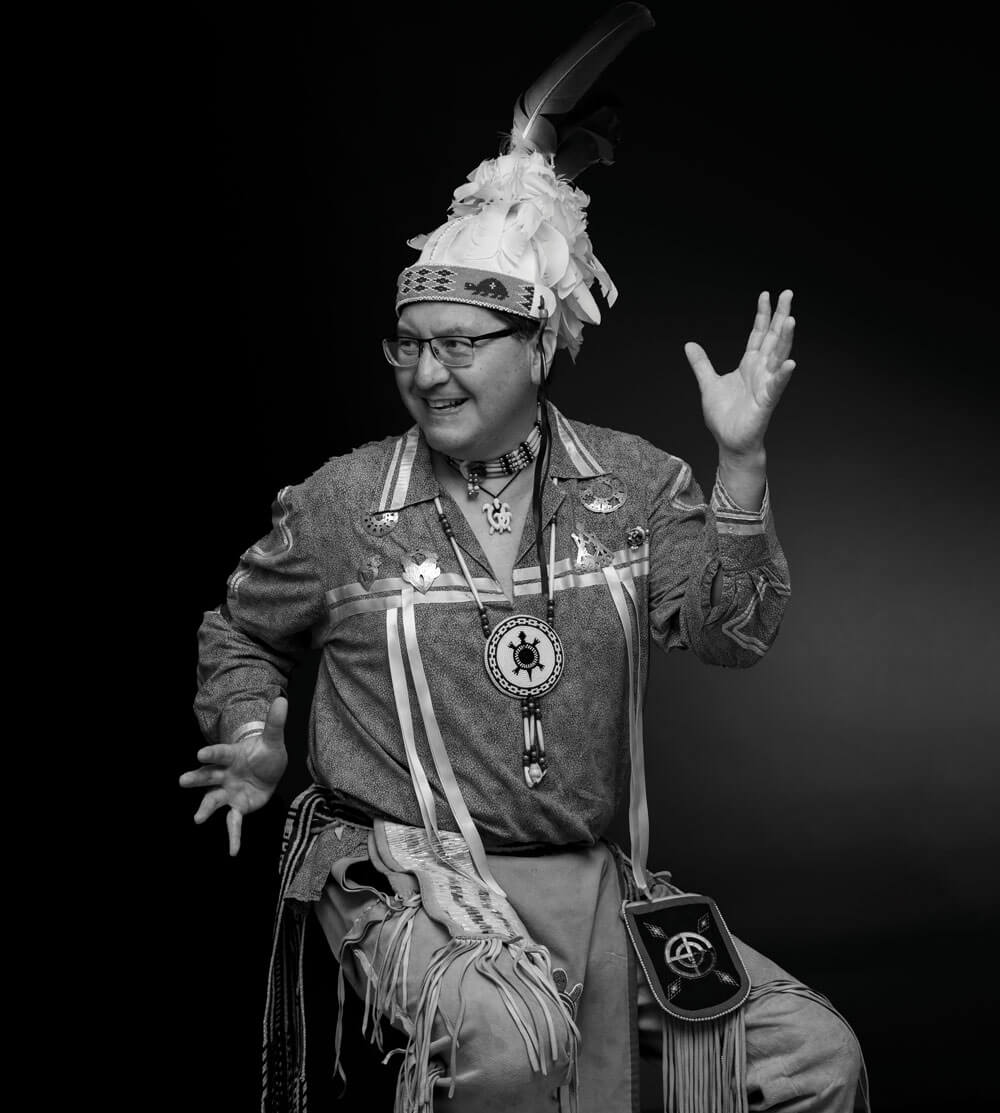

Perry Ground, an educator and storyteller from the Turtle Clan of the Onondaga Nation, became the latest person to serve as Frederick H. Minett Professor 30 years after the yearly appointment began under former RIT President Albert J. Simone.

Ground becomes the second Native American individual to hold the title of Minett Professor, following G. Peter Jemison from 2007-2008. The first person to serve the role was Wyoma Best, a former local news reporter and anchor and vice president of marketing and communications for the Rochester Chamber of Commerce.

Others who have served as Minett Professor include former mayor of Rochester William Johnson (1993-1994) and retired Kodak chemist and member of the University of the State of New York Board of Regents Walter Cooper (1996-1997).

This fall, Ground will offer public lectures about topics related to Native American history and culture. In the spring, he hopes to teach classes on the Native people of New York through the Haudenosaunee worldview, and on Native American storytelling, pulling perspectives from different tribes from across the country.

“It’s wonderful that RIT is bringing in various cultures from around the greater Rochester area to campus to try to connect the campus community with the local cultural communities,” Ground said.

A growing need

While faculty diversity has increased some at universities across the nation over the past several decades, the growth in student diversity has far outpaced it. A study from the National Center for Education Statistics showed that in fall 2017, 76 percent of postsecondary faculty were white, but only 55 percent of undergraduate students were white.

In the fall of 2020, 75 percent of RIT faculty were white, while 62 percent of RIT undergraduate students were white.

This summer, the university unveiled a new Action Plan for Race and Ethnicity, a series of initiatives aimed at making the university more diverse, equitable, and inclusive.

One of the three key pillars of the plan focuses on faculty and staff recruitment, retention, and advancement.

The plan outlines several strategies for the university to roll out over the next three years aimed at helping to close the gap in diversity between faculty and students.

Lorraine Stinebiser, director of faculty diversity and recruitment, said closing the gap won’t be easy.

“Faculty diversity is on the radar of every single institution,” Stinebiser said. “There has been a growing number of recruitment programs offered, including recruitment models similar to FFCEP. There’s competition all around. We need to continually work on developing new relationships and programs.”

FFCEP has long been an important avenue for RIT to grow diversity in the faculty ranks. Launched in 2003, the program has hosted hundreds of AALANA scholars since its inception, 23 of whom—including Borrego—have joined RIT’s faculty ranks.

Donathan Brown, assistant provost and assistant vice president for faculty diversity and recruitment, said he and his team work hard to prepare program participants for their next step—whether it is at RIT or somewhere else.

“In my mind, it’s not enough to engage you about RIT if I’m not providing at least some guidance about how to apply to RIT and beyond,” said Brown. “Our conversation is not only about RIT, who we are, what we do, and our current faculty and fellowship opportunities. We also talk about creating competitive faculty applications.”

Assistant Professor Katrina Overby participated in the program the same year as Borrego, joined RIT’s School of Communication in the College of Liberal Arts as a postdoctoral researcher in 2019, and transitioned to a tenure-track faculty role this fall.

Assistant Professor Katrina Overby joined RIT’s School of Communication in the College of Liberal Arts as a postdoctoral researcher in 2019 and transitioned to a tenure-track faculty role this fall.

“Each year the program is building a cohort of people who have something in common and they don’t know where those relationships can go,” said Overby. “So, as a byproduct, RIT is instrumental in sort of creating space for groups of minority scholars to come together and learn from one another and encourage each other.”

Overby has a wide, interdisciplinary range of research interests that include Black Twitter, social media and culture, African American cinema, race and identity in television and popular culture, sports media, and the scholarship of teaching and learning.

She said she still keeps in touch with many of her fellow FFCEP participants, and has collaborated with some on research, brought them to guest lecture in her class, and may even start a podcast with a fellow participant.

Overby said the program is important because it closely mimics the job interview experience in a lower stakes environment. She said she wishes more universities offered programs like it because it helps undermine the false assumption many search committees have that there are not enough quality diverse candidates.

“FFCEP says they’re here and we’re going to bring them to you to show you the quality of scholars that are out there that you may be overlooking,” she said. “RIT has a model program that should be mimicked elsewhere at other institutions.”

Building a community

The Office of Faculty Diversity and Recruitment (OFDR), led by Brown and Stinebiser, supports the faculty search process by working with search committees to increase the diversity in candidate pools for every posted faculty search.

Since Brown assumed his role in 2019, OFDR has built a scholars network of more than 700 women and AALANA faculty, postdoctoral researchers, and MFA and Ph.D. students from more than 140 universities across the country. When a faculty opening at RIT is posted, OFDR engages with search committees to identify AALANA and woman scholars for referral by querying the scholars network, as well as other resources of diverse scholars offered by organizations such as the Southern Regional Education Board and The Ph.D. Project.

Illustrations by Sarah Keane

Brown said his office has been able to quickly build its scholars network by not relying on the annual or biannual conference as its sole method of faculty recruitment.

“Such a passive approach exposes us to risks that are outside of our control, such as failing to engage excellent and diverse scholars and artists who simply cannot afford to attend,” said Brown. “My vision is to meet people where they are on college campuses. We are engaging predominantly white institutions who graduate the highest number of women and AALANA graduates in the areas we serve at RIT, in addition to historically Black colleges and universities, Hispanic serving institutions, and Native American scholars initiative universities.”

While the pandemic has limited in-person outreach, Brown and Stinebiser have been using Zoom to meet with prospective faculty. They rolled out a new Pathways to RIT virtual program that engaged nearly 70 scholars and artists in an academic open house. They also launched the #IamRITfaculty social media campaign to celebrate RIT’s diverse scholars in a personal and professional manner.

In addition to recruiting diverse faculty, another key factor for RIT’s goal of improving faculty diversity is ensuring that AALANA scholars stay and thrive.

Marcos Esterman, a professor in the Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering, believes that comes from creating a positive campus climate and a strong culture of mentorship, particularly for young scholars.

Esterman was part of the first ever cohort of FFCEP in 2003. He was one of three participants to join RIT as faculty, along with Associate Professor Robert Osgood from the Biomedical Sciences Program, and Associate Professor Edward Brown from the Department of Biomedical Engineering.

Esterman said when he was asked to participate in FFCEP, he was working at Hewlett Packard and had no intention of making the move from industry to academia.

Transforming RIT: The Campaign for Greatness

The campaign is RIT’s $1 billion fundraising effort, the largest in university history. The first pillar of the campaign focuses on attracting exceptional talent. One of the campaign’s goals is to increase underrepresented faculty proportional to the number of underrepresented students since students are more likely to thrive in a setting where there are faculty with whom they can identify. This blended campaign seeks support from a variety of investors, including alumni and friends, government and corporate partners, and research foundations and agencies.

“My view of academia at the time was that an academic career would be something I would eventually retire into,” said Esterman. “When I was invited, I viewed it as a networking opportunity, as a chance to learn more about the academy, but I was very happy with my role at HP and saw very little chance of making a move. Obviously, that’s not what transpired.”

He said when he visited RIT, he found a tight-knit community that looked out for one another. He was intrigued, and after talking with other diverse faculty members who had moved from industry to academia, he realized he should not wait until retirement to make the change. Since then, he has climbed the faculty ranks and served as the university’s faculty associate to the provost for ALANA faculty from 2013-2019.

“Certainly there are systemic things we can do to help retain diverse scholars, but to me that department head to faculty relationship is key,” said Esterman, who was promoted to full professor this fall. “If you have good foundations there supported by good mentorship within the college and someone feels welcomed, it will go a long way.”

Marcos Esterman, now a full professor in the Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering, was part of the first ever cohort of the Future Faculty Career Exploration Program in 2003.

Unique challenges

Back in his office in Gosnell Hall, Borrego reflects on what helped him and what universities need to do more of to further diversify faculty. While there are many systemic issues that need to be addressed, he said the roots of some of those problems extend all the way back to grade school.

“I’m a first-generation college student and academia is so far removed from my culture, my community, and my background,” he said. “By the time I was in high school, my parents couldn’t help me with my studies and applying to college was even more difficult.”

He said AALANA scholars are more likely to be first generation and underprivileged, so they need early resources and especially excellent mentors to understand how the academic game is played and to prepare them for it.

Borrego also noted a recent study led by University of Colorado-Boulder scholars found that tenure-track faculty are 25 times more likely to have a parent with a Ph.D. than the general population, and that faculty with Ph.D.-holding parents are more likely to be employed at elite universities.

Furthermore, he noted that many of the key stepping stones to become a faculty member are unavailable to those who cannot afford them.

“There are opportunities to get research experience and potential publications as an undergrad student, but many are through unpaid internships that unless you’re already able to afford not working, you can’t participate,” Borrego said. “There are also paid summer internships, but sometimes you don’t even know that they exist and that you should be applying for them. The reason I’m here is because my undergraduate and graduate mentors told me to go do these things, gain these experiences, and I said, ‘OK.’ I am very grateful to them.”

Borrego said he’s also grateful for programs like FFCEP that helped him find a home where he can do meaningful work in a positive environment.

“Everyone here is really friendly and that’s something I wanted—a community that was interacting with each other,” said Borrego. “Since I do agricultural work and that’s an area that RIT wants to move into, it’s been a great opportunity to jump in at the initial level, help guide the areas they need, and start my research program.”