Leaves of Gold

Using digital imaging techniques, RIT scientists preserve an ancient Hindu text

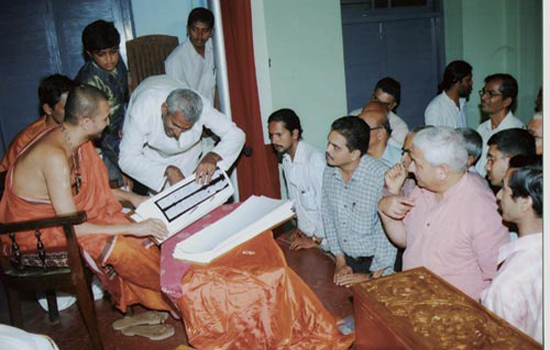

Research scholars in Udupi, under the supervision of Shri Vidyadheesha Tirtha Swamiji, examine the final printed version of the restored Sarvamoola Granthas.

Using modern imaging technologies, RIT scientists have digitally restored a 700-year-old palm-leaf manuscript containing the essence of Hindu philosophy.

The project led by RIT professors P.R. Mukund and Roger L. Easton Jr. has digitally preserved the original Hindu writings known as the Sarvamoola Granthas, attributed to philosopher-saint Shri Madhvacharya (1238-1317). This collection of 36 works written in Sanskrit contains commentaries on sacred Hindu scriptures and conveys the scholar’s Dvaita philosophy of the meaning of life and the role of God.

Dvaita is one of the three major schools of thought related to Hindu philosophy. According to Mukund, this philosophy stresses “monotheism and the concept of one God who is the supreme Lord of all beings.”

Dvaita philosophy differentiates between souls, God and matter,” Mukund says. “God is all knowing, all powerful, all pervasive. He is even beyond nature.”

Each leaf of the manuscript measures 26 inches long and two inches wide. The leaves are bound together with braided cord threaded through two holes. Heavy wooden covers sandwich the 342 palm leaves, which are cracked and chipped at the edges. In its current condition, the Sarvamoola Granthas is difficult to handle and to read as the result of centuries of inappropriate storage, botched preservation efforts and improper handling. The passage of time and a misguided effort to preserve the manuscript with oil have turned the palm leaves dark brown, obscuring the Sanskrit text, and the aging leaves shed bits of the sacred scriptures every time it is touched.

Palm leaves were commonly used as a writing material before the advent of printing due to their abundance throughout the region and durability once dried and polished. Monasteries across Southeast Asia house stacks of decaying palm-leaf manuscripts of varying importance. Mukund is seeking funding to image other Dvaita manuscripts in the Udupi region written since the time of Shri Madvacharya. He estimates the existence of approximately 800 palm-leaf manuscripts, some of which are in private collections. None are as important, however, as the decaying Sarvamoola Granthas.

“It is literally crumbling to dust,” says Mukund, RIT’s Gleason Professor of Electrical Engineering. According to Mukund, 15 percent of the manuscript has already deteriorated.

“Every time the manuscript is opened, some more of the palm leaves disintegrate, leading to further loss of the manuscript,” he says. “This has resulted in the manuscript being sequestered in a matha, or monastery, thereby making it inaccessible to scholars. After this digital restoration is completed, there won’t be a need to open the manuscript again.”

Preserve and protect

Mukund first became involved with the project when his spiritual teacher in India brought the problem to his attention and urged him to find a solution. This became a personal goal for Mukund, who studies and teaches Hindu philosophy or “way of life” and understood the importance of preserving the document for future scholars.

The Sarvamoola Granthas contains commentaries on various important scriptures and analysis of the holy texts such as the Vedas, Upanishads and other Hindu scriptures. Shri Madvacharya’s writings are upheld as the definitive interpretation of the Vedas and of the structure of the spiritual world. Preserving a record of the Sarvamoola Granthas in its original form is intrinsically important for future scholars, especially since the accuracy of existing printed copies is unknown.

“Society depends upon scholars for strength,” Mukund says. “All people of faith depend upon scriptures for strength. Where do the scriptures get their strength? All scriptures get their strength from God. This is much more important than, say, a temple. In these works, God is residing in His true form, whereas a temple is only man-made.”

For advice in preserving the writings of this valuable document, Mukund sought the expertise of RIT colleague Easton, who imaged the Dead Sea Scrolls and is currently working on the Archimedes Palimpsest (see accompanying article page 11). Easton, a professor at RIT’s Chester F. Carlson Center for Imaging Science, brought in Keith Knox, an imaging senior scientist at Boeing LTS, as a consultant. Mukund added Ajay Pasupuleti ’06 (Ph.D., microsystems engineering), to complete the team.

“The literature we are trying to preserve has tremendous impact on society,” Ajay Pasupuleti ’06.

The scientists traveled to India in December 2005 to assess the document stored at a monastery in Udupi. Sponsored by a grant from RIT, the team returned to the monastery in June 2006 and spent six days imaging the document using a scientific digital camera and an infrared filter to enhance the contrast between the ink and the palm leaves. Images of each palm leaf, back and front, were captured in eight to 10 sections, processed and digitally stitched together. The scientists ran the 7,900 total images through various imaging processes using Adobe Photoshop and Knox’s own custom software.

“This is a very significant application of the same types of tools that we have used on the Archimedes Palimpsest,” Easton says. “Not incidentally, this also has been one of the most enjoyable projects in my career, since the results will be of great interest to a large number of people in India.”

Deeply Meaningful

The processed images of the Sarvamoola Granthas will be stored in a variety of media formats, including electronically, in published books and on silicon wafers for long-term preservation. Etching the sacred writings on silicon wafers was the idea of Mukund’s philosophy student Pasupuleti. The process, called aluminum metalization, transfers an image to a wafer by creating a negative of the image and depositing metal on the silicon surface.

According to Pasupuleti, each wafer can hold the image of three leaves. More than 100 wafers will be needed to store the entire manuscript. As an archival material, silicon wafers are both fire- and waterproof, and readable with the use of a magnifying glass. No other technology is required to access the information recorded on the wafers. Transferring the Sarvamoola Granthas to silicon wafers is the next phase of the project, pending future funding.

“It was a fantastic and profoundly spiritual experience,” said P.R. Mukund, Gleason Professor of Electrical Engineering.

“I feel blessed to get this unique and wonderful opportunity,” Pasupuleti says. “The literature we are trying to preserve has tremendous impact on society. As a result, I am extremely thrilled to contribute my time and technical knowledge towards this project.”

Pasupuleti is a native of India who came to RIT in 2000 to begin work on a master’s degree in electrical engineering. He recently earned his doctorate in microsystems engineering and plans to continue working on the Sarvamoola Granthas project.

“We feel we were blessed to have this opportunity,” Mukund says. “It was a fantastic and profoundly spiritual experience. And we all came away cleansed.”

The professor and his student returned to India at the end of November with two bound copies of the Sarvamoola Granthas. The books were printed at RIT with the help of John Eldridge, digital printing technologist, and his colleagues in the School of Print Media in the College of Imaging Arts and Sciences.

“They went out of their way to help,” Mukund says.

Mukund presented the books in hand-carved teak boxes to his spiritual teacher and to the head of the Udupi monastery in an emotional public ceremony covered by The Times of India.

Unexpected developments

News of RIT’s efforts to digitally restore the Sarvamoola Granthas has led serendipitously to two developments. The first opportunity came from Charles White, professor emeritus at American University, who had traveled extensively throughout India in the 1980s on behalf of the Smithsonian Institute and microfilmed more than 1,000 Hindu manuscripts, including palm leaves and printed works.

Impressed by the Sarvamoola Granthas project, White offered Mukund his own microfilm collection to digitally restore. The American University gave Mukund a copy of White’s 76 reels of microfilm containing more than 20,000 pages of Vaishnava literature. The collection contains Hindu sacred literature dating from 100 to 1,000 years ago, including hymns and prayers, as well as extensive commentaries on the Sarvamoola Granthas by various scholars.

Mukund traveled to Washington, D.C., twice in December 2006, first to meet White and to accept the first installment of microfilms, then to pick up the remaining reels. Mukund is stunned by the overture.

“It would be as if all the Catholic literature was handed to someone,” he says. “It’s that big.”

The collection is not in outstanding shape due to the condition of the original works and aging of the microfilm. The imaging team will scan and digitize each reel, then process and enhance the images. The digital documents will be printed on archival paper and bound into books. Mukund anticipates the microfilms will yield approximately 1,000 books that scholars lack access to today.

The larger aspect of the project will include creating a detailed catalog of the hard copy and digital documents according to schools of thought. The digital documents will remain at RIT. The hard copy documents will be housed at the Sri Venkateswara Central Library and Research Centre in the town of Tirupati, an ancient pilgrimage destination in southern India.

A senior government official who had learned of White’s gift to Mukund offered to dedicate a wing of the library as a repository for the collection. This second unexpected development has pushed the project forward and given it a tight deadline coinciding with the inauguration of the dedicated library space in August. To complete the project in time, Mukund and Easton will establish a lab at RIT and hire two full-time post-doctoral fellows.

The realization of both projects – transferring the Sarvamoola Granthas to silicon wafers and digitally preserving the vast collection of Vaishnava literature – depends on adequate funding. Mukund is currently accepting donations for both efforts. Mukund, his students and Easton have personally donated more than $25,000 to the project and seek another $75,000 to cover expenses. Interested donors can contact Mukund by telephone at 585-475-2174.