Lost art

Graduates bring new life to letterpress

A. Sue Weisler

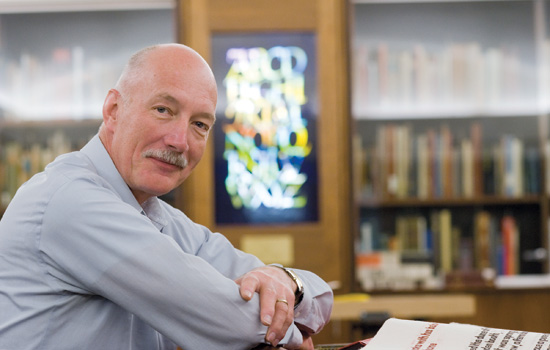

David Pankow, curator of the Melbert B. Cary Jr. Graphic Arts Collection, will retire Aug. 31 after working at RIT for more than 30 years.

Tony Zanni ’07 (graphic design) opens a drawer from a cabinet built at the turn of the 20th century and pulls out a piece of wood type.

“That looks good, let’s use that,” says Zanni, who has more than 150 wood typefaces and more than 600 cases of lead type to pick from.

The graphic designer starts assembling, sometimes copying a drawing and other times just using a type size and style that fits.

The result is a card, an invitation, a flier or a poster—each with its own look and feel. The images and fonts may seem straight out of the early 1900s, but the designs are strikingly current.

And that, says David Eckler ’83 (printing management), is one reason for the resurgence of letterpress printing—putting ink on raised characters or images and pressing it into paper. Eckler is the owner of Dock 2 Letterpress, a commercial letterpress business in Webster, N.Y. Zanni is his creative partner.

They share a passion for letterpress printing with other RIT graduates and former professors, including Bill Dexter ’76 (printing), Mitch Cohen ’76 (printing) and Professor Emeritus Joe Brown, who have been collecting antique presses and type for decades. Dexter, Cohen and Brown teach letterpress and papermaking at a nonprofit arts center in Rochester.

They have the same goal: Keep the craft—which uses equipment that only years ago was considered outdated and worthless—alive.

David Pankow, curator of the Melbert B. Cary Jr. Graphic Arts Collection at RIT, which includes books on the history of printing as well as historic printing presses and type, says one reason for the current interest in letterpress is photopolymer plating. Designers can make an image on a computer, convert the file into a negative image and make that into a plastic plate, which when inked and printed carries the same embossed effect as lead or wood type.

Traditional letterpress, on the other hand, provides a link to the past, Pankow says. The process of working with metal type forces designers to remember the importance of white space. On a computer, it’s easy to add unneeded layers and to crowd typefaces.

“To me that’s a very liberating attitude to bring to design,” Pankow says. “You don’t need to feel like you have 1,000 typefaces on your computer. In the hands of a great designer, having less is more.”

Teaching a craft

Brown’s blue eyes smile when he talks about his papermaking classes at the Genesee Center for the Arts and Education the same way they do when he talks about RIT’s School of Printing in the 1970s and ’80s.

In the early 1980s, there were more than 800 undergraduates in the School of Printing and the top-notch program was known all over the United States, he says. Many of those students came from families that ran small printing plants.

But as technology changed the printing industry and pre-press work could be done on a computer, many of those printing presses went out of business and enrollment declined. In the early 1990s, Brown retired and he thought his days of teaching printing technology and papermaking were over.

He salvaged some papermaking equipment and a Vandercook 4 antique press, thinking he could continue his craft as hobby. But it sat in his garage collecting dust—until Dexter called in 2005.

“I said, ‘This is Bill Dexter, your first lab assistant,’ ” Dexter remembers. “ ‘Here’s what we are doing.’ He said, ‘Don’t buy anything.’ ”

By that time, Dexter and Cohen had already connected with the Genesee Center, which had space available and was interested in adding a printing and book arts program to its pottery and photography classes.

Cohen, who had owned a printing business and had worked as an estimator, had always wanted to open a printing center or a museum and make letterpress equipment he had in his garage and basement available to the public.

He had stayed in touch with Dexter, who had his own press stashed away. They opened the printing and book arts program in November 2005.

“Our mission is to promote and preserve the art of letterpress,” Cohen says.

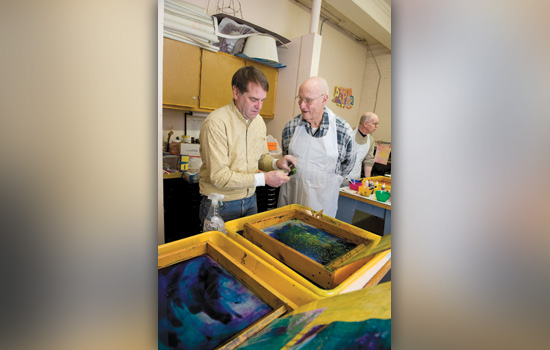

Brown and Dexter, who is a self-employed graphic artist, teach papermaking courses. Cohen, now a job developer, specializes in letterpress printing. They teach a papermaking class once a month along with weekly letterpress classes. Others teach bookbinding and calligraphy classes at the center.

Cohen, who is director of the printing and book arts component at the Genesee Center, says along with classes, the program also rents space to about 14 artists.

Brown, who is a board member at the Genesee Center, says both papermaking and letterpress attract people who want to work with their hands and get away from constant technology. The craft allows them to make something personal.

He uses the example of a woman who stopped by the center to make her daughter’s wedding invitations. First she made the paper. Then she set the type and printed them on the letterpress.

“I just love teaching again,” Brown says. “I have found a home at the Genesee Center.”

Making a business

Eckler first got interested in letterpress in his ninth-grade shop class. He started collecting type and presses and worked out of his grandmother’s garage on weekends.

After high school, Eckler worked as a pressman while attending night classes at RIT. He continued collecting letterpress equipment and type, mainly from men who were a generation older than him and who were given the equipment after local companies switched to offset printing.

“From 1970 to 1990, I’m going to houses and taking grandpa’s print shop out of the basement,” Eckler says. “They knew I was the next generation of letterpress.”

Meanwhile, Zanni had never thought about letterpress printing until 2001. He met a friend of Eckler’s with a barn full of letterpress type and presses. Realizing the creative possibilities, he bought some equipment from Eckler.

The two joined forces in 2008 when they learned that Linda and Robert Bretz wanted to sell their letterpress collection. Robert Bretz was the first librarian for the Cary Collection. They bought it and a year later opened Dock 2 Letterpress.

Now the business has 11 working presses, including a hand press from the 1900s. Ray Czapkowski, who attended classes at RIT in the early 1960s and worked as an adjunct professor in the communications department in the early 1980s, is their resident expert and teaches letterpress classes on the weekends. Czapkowski says RIT design students often enroll in his classes.

“I love sharing my knowledge,” says Czapkowski, who worked as a type compositor before owning a printing business in Rochester. “I thought this was all dead in the 1950s and suddenly I’ve become a guru.”

Adds Eckert: “It is great for me to know all of the stuff sitting in a barn for all those years is being used.”

TO LEARN MORE

To get more information about the Genesee Center for the Arts and Education in Rochester, go to www.geneseearts.org.

For more on Dock 2 Letterpress in Webster, N.Y., go to dock2letterpress website.

Curator who made lasting impression retires

David Pankow had only planned to stay at RIT for a few years when he came in 1979 to be the Cary librarian.

Then the position was restructured in 1983 and Pankow added the job of curator of the Melbert B. Cary Jr. Graphic Arts Collection to his librarian responsibilities.

“It seemed as though at every point I thought I had done as much as I could here, some new opportunity came along,” Pankow says.

Pankow grew the collection from 5,000 books to 40,000 books. He assembled antique printing presses and type that help tell the story of printing. He helped acquire the Bernard C. Middleton collection of books on bookbinding, the most important collection in the United States on the history and practice of bookbinding. And he started the Cary Graphic Arts Press, which opened in 2001.

Now, more than 30 years later, Pankow is ready to pass the next set of challenges to others. He will retire Aug. 31.

“What I’ll miss the most is that sense that every new day brings another potential project to work on or another group of students to teach,” he says.

Pankow, 63, wants to do his own writing and scholarship work. His position is being split into two jobs, a curator for the Cary Collection and director of the Cary Graphic Arts Press.

Pankow came to RIT after working at the New York Public Library for seven years. At that time, the Cary Collection, which was originally established in 1969 as a small library based on Cary’s personal collection of books on printing history and graphic arts, was in the School of Printing. In 1991, the collection moved to the second floor of Wallace Library. The Cary Graphic Arts Press is adjacent to the collection.

Amelia Hugill-Fontanel, assistant curator and the first employee for Cary Graphic Arts Press, says Pankow has diverse talents that go beyond being a teacher and scholar. He can typeset a broadside, bind a book, mat a poster or edit a manuscript.

“Because he is so knowledgeable about many aspects of history, he has a wonderful vision of the big picture,” says Hugill-Fontanel, who has become Pankow’s apprentice of sorts in letterpress printing.

Pankow says although he feels conflicted about retirement, he is happy there are people who will continue his interest in the Cary Collection and letterpress printing.

“I think I have had the greatest job at RIT,” Pankow says. “I work in a beautiful setting surrounded by beautiful books. If Mr. Cary came back today he would walk around the collection and feel we had honored his spirit.”

Tony Zanni ’07 works on a poster at Dock 2 Letterpress. He says letterpress allows people to create something with their hands.

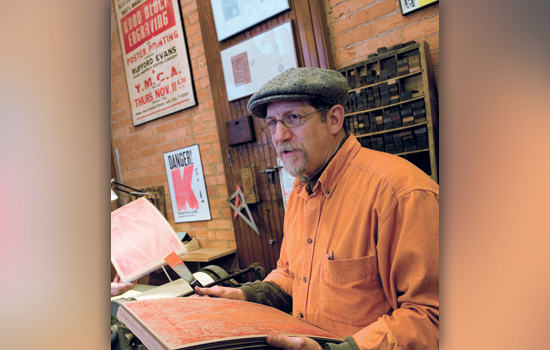

Tony Zanni ’07 works on a poster at Dock 2 Letterpress. He says letterpress allows people to create something with their hands. Mitch Cohen talks about the resurgence of letterpress printing.

Mitch Cohen talks about the resurgence of letterpress printing. David Eckler ’83 planes a form before loading it into the press. He is pleased that all the antique equipment he collected is being used.

David Eckler ’83 planes a form before loading it into the press. He is pleased that all the antique equipment he collected is being used. Bill Dexter, left, and Professor Emeritus Joe Brown marble paper at the Genesee Center for the Arts and Education in Rochester.

Bill Dexter, left, and Professor Emeritus Joe Brown marble paper at the Genesee Center for the Arts and Education in Rochester.