Manifesting Quantum

In 1925, German physicist Werner Heisenberg published a paper on quantum mechanics, upending classical physics and launching the world into the quantum age.

Now, 100 years later, researchers across RIT’s campus are utilizing quantum in a variety of disciplines to continue to push the boundaries in science, engineering, and technology.

While classic physics explains the behavior of objects in everyday life, quantum mechanics examines how atoms and light interact on the nanoscale. Studying matter in its smallest form is complex, which is why understanding quantum has only really begun in the past century.

RIT researchers are zeroing in on quantum photonics, the creation, control, and detection of light. Photonics has long been a specialty of the university. RIT led the team that developed the first quantum photonic wafer, which is key to the future of mass-produced quantum communication systems.

“Using photons the way that we formerly used electrons is going to make everything smaller, cheaper, faster, better,” said Ryne Raffaelle, vice president for Research.

Researchers are also putting quantum theory into action with the goal of building quantum computing systems. At the same time, experts must prepare for cybersecurity threats in the quantum era.

“Quantum has been worked on and theorized for a long time, and we are at the point where it is manifesting,” Raffaelle said.

In other words, RIT researchers are taking theory imagined in old science fiction movies and engineering it into reality. Keep reading to see how.

Why study quantum?

If researchers can figure out how to control the unpredictable nature of atomic and subatomic particles and waves, they will be able to solve complex problems that are too difficult for current computing systems. This could include drug discovery; optimization of supply chains, logistics, and energy grids; and enhanced artificial intelligence.

Rochester’s optics legacy powers the quantum future

Story by Mollie Radzinski

Computers have always been an interest of Stefan Preble ’02 (electrical engineering), professor in the Department of Electrical and Microelectronic Engineering.

In the early internet days, Preble was tying up his parents’ phone line so much they got him his own dedicated line. Fast forward, and now Preble is working to change the world of internet communication with an experimental quantum network.

Through a partnership with the University of Rochester, the Rochester Quantum Network (RoQNET) is an 11-mile network that uses single photons to transmit information between the two campuses along fiber optic lines. While quantum communication networks exist around the country and the world, this is the first centered on quantum photonic chips.

Quantum communication networks have the ability to change the way information is sent and received because they provide a more secure network where messages cannot be cloned or intercepted without detection.

Quantum bits, or qubits, make these networks possible. Qubits can be created in numerous ways, but photons (individual particles of light) are proving to be the best type of qubits for communication networks because they can be transmitted over already existing fiber optic lines.

With its legendary history in optics, the Rochester region was the ideal place to make a photonics-based quantum network a reality.

“Rochester has always been a significant contributor to optics, so who else is going to do it?” said Preble. “It’s on us to establish this and hopefully it will be a legacy down the line when we have these quantum technologies.”

The region’s expertise in microchip technology has also positioned RIT to be a leader in quantum communication. Sophisticated microchips are needed to process the photonic quantum states.

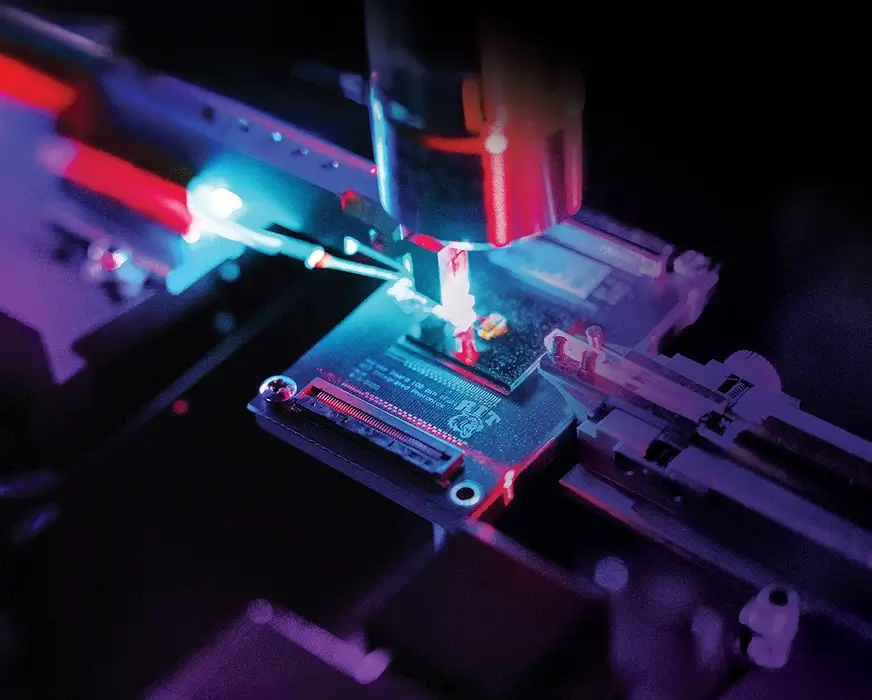

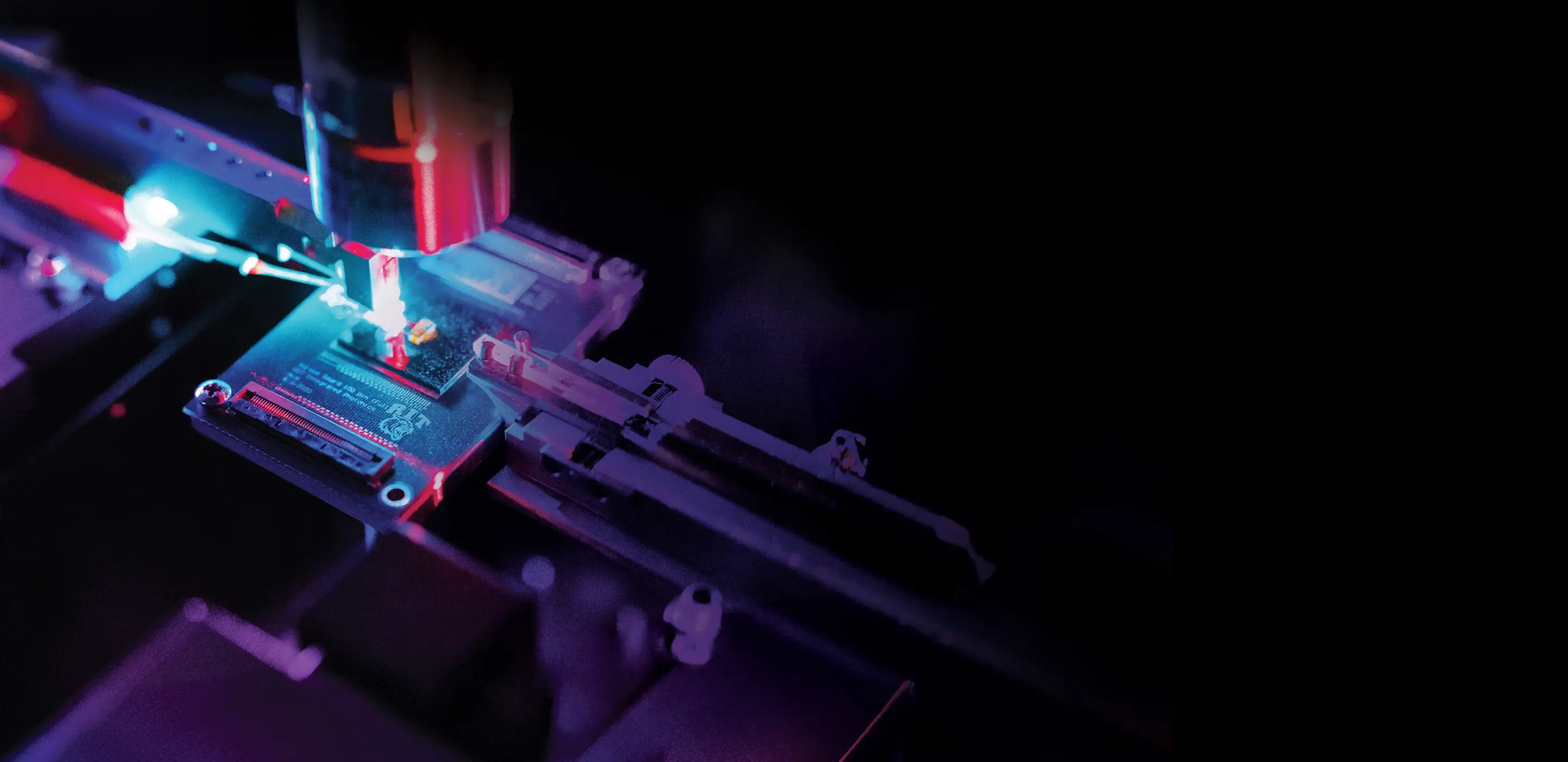

In 2020, Preble and a team of RIT’s Future Photon Initiative researchers collaborated with the Air Force Research Laboratory to produce the Department of Defense’s first-ever fully integrated quantum photonic wafer.

Wafers are used to mass produce integrated circuits or microchips and help with research in quantum photonics. The wafers allow for experiments that need a large, optical table to be scaled down to a tiny microchip, making it possible to explore bigger, more complex systems, specifically in quantum computing.

Preble’s expertise in integrated photonics dates back to his days as an undergraduate student, where he first became interested in quantum. After completing his bachelor’s degree at RIT, Preble attended Cornell University to receive his Ph.D. in electrical and computer engineering, where he was introduced to the new field of silicon photonics.

While light circuitry on a microchip had been investigated previously, it wasn’t being done on silicon at the time. Nanostructures made with silicon were well developed for the electronics industry, so being able to adapt the same material for photonics allowed it to scale up commercially very rapidly.

Once Preble started job searching, a position at RIT in silicon photonics came to his attention. He applied, was hired, and now he is pushing the world of quantum silicon photonics forward.

“I was compelled by the silicon photonics research of my Ph.D. adviser, and I was attracted to the fact that I could combine my ongoing interest in quantum with the newly emerging field of photonic microchips,” said Preble. “Microchips are able to address the challenges of scaling quantum photonic systems.”

What is photonics?

Photonics is the study of light and its uses. A photon is a single particle of light. Photons are quantum particles because they are the smallest units of light.

As the graduate program director of the microsystems engineering Ph.D. program, Preble guides the next generation that will keep moving quantum technology forward.

One such student, Vijay Sundaram ’21 MS (physics), was the lead author for a RoQNET paper that was published in Optica Quantum. Like many kids, Sundaram wanted to be an astronaut when he got older, so he went into aerospace engineering in his home nation of India, but he shifted to physics for his master’s degree at RIT.

During that graduate program, he discovered that astrophysics is math intensive, with a lot of work in computer simulation. Sundaram was more interested in experimental science and being in a lab. A quantum optics course steered him in the direction of microsystems engineering, where he is now on the forefront of a budding new field.

Sundaram recognizes that the first fully working quantum computer could be decades away, but his work now and in his future career makes it a possibility. Private companies like IBM and Google, and public entities like the Air Force, are already working toward a quantum future. There is a wide range of career opportunities for Sundaram in quantum technology.

“There’s quantum for finance, for security, for communication,” Sundaram explained. “You can apply this to pretty much everything. The applications are endless.”

Just as it was fortuitous that Preble entered a Ph.D. program as a new field was growing, now Sundaram and Preble’s other advisees can get involved in quantum as it begins to shape the world.

“Each one of my students has gone on to great success,” said Preble. “They are at top research institutions in the world and leading global research. Working with students is the most rewarding aspect of this job.”

What is photonics?

Photonics is the study of light and its uses. A photon is a single particle of light. Photons are quantum particles because they are the smallest units of light.

Experts prepare for cyber threats in the next era

Story by Scott Bureau

Quantum technology is going to have at least one unintended consequence—cybersecurity threats.

Quantum computers will make many of the cryptographic methods used in today’s secure systems obsolete. While quantum-resistant cryptography is being developed, the changeover process will still put many of the systems that people use every day at risk.

At RIT, cybersecurity researchers are preparing for a world with powerful quantum computers by making systems more reliable and safer. Most notably, faculty and student experts are improving the security of connected vehicles. In the process, the team hopes to reduce deaths on the road.

“Quantum-resistant algorithms will eventually help, but they aren’t just plug and play—that could break the whole system,” said Hanif Rahbari, associate professor of cybersecurity. “The transition from classical cryptography to post-quantum crypto needs to be done with no interruption to the function of systems. People aren’t going to sit at home and wait.”

Rahbari began researching vehicle-to vehicle (V2V) communication nearly a decade ago. When equipped with this technology, vehicles can wirelessly exchange speed data, location, and alarms to improve traffic flow and prevent accidents. Cryptographic integrity and authenticity are essential for ensuring that messages between vehicles are not malicious.

During his first years at RIT, Rahbari was approached by a group of mathematics and cryptography researchers from the University of Waterloo, Canada. They were developing quantum-resistant algorithms and wanted Rahbari’s expertise.

“At first, I wasn’t sure how I could contribute to quantum—it felt distant from where I was,” said Rahbari. “But not everyone needs to know everything about quantum to be able to work in this multidisciplinary field. We need complementary expertise to collaborate and tackle these problems.”

Right away, the team saw that quantum-resistant algorithms could disrupt the safety benefits of connected vehicles. These algorithms bring about a lot of bandwidth, latency, and other overhead issues. For systems with constraints, adding post-quantum crypto could be disruptive and even exploited by attackers.

Up on the third floor of RIT’s ESL Global Cybersecurity Institute, Rahbari’s research group is putting systems and protocols to the test. The work is part of his prestigious NSF CAREER award, a five-year grant.

While the researchers don’t have 100 cars to test on real roads, they are developing an interactive digital twin as a measurement framework. The simulation resembles a racing video game and mirrors the real world.

What is cryptography?

In computing, cryptography is the process of using codes or algorithms to secure information. Cryptographic integrity ensures that messages haven’t been corrupted or tampered with by unauthorized parties. In the quantum computing era, cryptographic mechanism will need to be more complex.

Geoff Twardokus, an electrical and computer engineering Ph.D. student leading the work, also enjoys using RIT’s Faraday Lab. The lab is a radio frequency-shielded space for safe wireless security experiments.

“We’re building up to a gold standard of real-world hardware experiments with actual V2V equipment that would be installed in cars,” said Twardokus, who is also a 2021 alumnus from RIT’s cybersecurity BS/MS programs. “We want to make sure that we can adopt this security without crippling the system that it’s supposed to protect.”

Congress has passed the Quantum Computing Cybersecurity Preparedness Act to encourage the transition to quantum-resistant cryptography. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is currently searching for better cryptographic algorithms designed to withstand cyberattacks enabled by quantum computers.

RIT’s team is measuring the impact of different candidates. In 2022, Rahbari, Twardokus, and University of Waterloo experts published research that shed light on the implications of post-quantum cryptography on V2V. That work was cited by NIST in standardizing algorithms.

As a Ph.D. student hoping to become a faculty-researcher in the future, Twardokus noted that the quantum security problem is much broader than vehicle communications. For example, many networking and industrial control systems that manage utilities infrastructure have similar constraints.

“Quantum is an important direction for us to focus on in cybersecurity,” he said. “You can develop a really fast quantum chip, but that could actually hurt us more than help us if we don’t properly prepare to combat those who might abuse it.”

What is cryptography?

In computing, cryptography is the process of using codes or algorithms to secure information. Cryptographic integrity ensures that messages haven’t been corrupted or tampered with by unauthorized parties. In the quantum computing era, cryptographic mechanisms will need to be more complex.

Engineers route the best path for quantum computing

Story by Michelle Cometa

When Sonia Lopez Alarcon took a sabbatical as a visiting scholar at NASA in 2018, she sought to discover more about quantum computing. She knew that before quantum technologies could be used in space, they needed to be further developed on Earth.

Lopez Alarcon, who was based at Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, worked with engineers and scientists who used high-tech computers to decipher intricate trajectory calculations and complex climate models.

“At the time, NASA was interested in understanding if quantum computing could effectively solve some of these problems,” she said. “This was very early exploratory work, mostly based on discussions and research related to quantum computing. It served as great examples of what we hope can be done in the future when research advances to practical applications.”

Today, Lopez Alarcon, a professor of computer engineering, is using her NASA experience—as well as her background in physics, integrated circuits, and computer architecture—to develop core computing functions to bring about those applications.

One of those functional areas is routing—how data moves across quantum computer systems. Figuring out how to move information through qubits—the quantum version of computer bits—puts researchers one step closer to building a quantum computing system that would allow people to work smarter and faster.

“The way that you tell electrons how to move is through high-level programming,” said Lopez Alarcon. “But there is still this challenge that is very much a computer engineering and a computer architecture challenge of how you control these quantum systems from a high-level programming language.”

In one of the many projects underway, Lopez Alarcon and her students are using machine learning to map optimal routes qubits must take along computer circuits. It is part of a new, three-year National Science Foundation (NSF) award that focuses on quantum compilation and routing to develop quantum circuits on specific computing architectures.

“The routing problem is a very big optimization problem where information from one part of the computing device must move to other parts of the device. It is computationally very intensive,” said Lopez Alarcon.

What are qubits?

Qubits are bits of information implemented, stored, and manipulated by quantum means. Scientists are trying to corral and then scale qubits, the way transistors were developed and then improved over time to become the main components of classical computers.

Electrical and computer engineering Ph.D. student Elijah Wangeman ’25 (computer science) likes that intensity. As an undergraduate, he took several classes with Lopez Alarcon, including three master’s level courses in quantum physics. He was hooked.

He came to RIT intending to become an astrophysicist, but his pivot toward quantum computing was not so much a shift away from one science but a shift toward combining interests in a growing field. It’s a field he can contribute to as a student and later as a researcher at a company or lab.

“As a computer scientist, the focus of my degree is language theory systems, and one of the core aspects is how programming languages, or compilation, works—how you get from the language used to program to the actual instructions that are delivered to the chip. This is so relevant to computer engineering and is relevant to quantum computing,” said Wangeman.

“If you want to work in quantum, it is dependent on you knowing so many things—the level of the infrastructure, the theoretical physics of quantum, and the mechanics,” he added. “RIT is a leader in computer science, computer engineering, software development, and cybersecurity. We have a unique opportunity to combine all these skills in quantum research being done here.”

Contributions that Wangeman and Lopez Alarcon will make are part of a larger, national effort to move quantum systems from theory to practice.

When Lopez Alarcon met with NSF program managers in fall 2024, she was among a large group of faculty-researchers from U.S. universities discussing their new grants and celebrating the 100-year anniversary of quantum theory. She and her peers were asked to consider the exciting possibilities their work might reveal a century later.

“Quantum technology is such an interdisciplinary domain and so many fields have a place in the quantum computing big picture,” Lopez Alarcon said. “We are building this from many perspectives, and it is an open opportunity for us as engineers and for our students.”

What are qubits?

Qubits are bits of information implemented, stored, and manipulated by quantum means. Scientists are trying to corral and then scale qubits, the way transistors were developed and then improved over time to become the main components of classical computers.

Researchers map quantum education efforts nationwide

Story by Mollie Radzinski

Photo by Scott Hamilton

As quantum continues to evolve from theory to application, an educated workforce is needed to scale up manufacturing and to adopt these tools in a range of industries, including aerospace, pharma, finance, and biomedicine.

Backed by funding from the National Science Foundation and the Department of Defense, a research team led by Professor Ben Zwickl has mapped where quantum courses can be found at higher education institutions across the country. The team is also in the process of interviewing quantum industry professionals to gain a deeper understanding of the landscape and needs of the quantum workforce.

“In order to grow quantum technology, you need people that know how to make, design, and build that technology,” said Zwickl. “There is a direct call to research the landscape of education opportunities in quantum science and quantum technology, to understand the jobs that are out there, and to bridge the gap between school and work.”

After a year of research, Zwickl and his team have created a database of all quantum courses offered at nearly 1,500 higher education institutions. At the end of the study, their goal is to have a more comprehensive picture of the quantum information science and engineering (QISE) education landscape. With this clear picture, guidance can be given to make the path into QISE more transparent for students from all backgrounds.

Zwickl is also an adviser for an interdisciplinary minor in quantum information science and technology at RIT. Enrollment has grown every semester since it launched in fall 2022, he said.

The minor is highly interdisciplinary in nature, with faculty from the College of Science, Kate Gleason College of Engineering, College of Engineering Technology, College of Liberal Arts, and Golisano College of Computing and Information Sciences offering classes that count toward the minor.

Classes available in the minor include introductions to quantum computing and other quantum technologies, linear algebra (the mathematical language of quantum computing), optics and lasers, quantum optics, quantum-resistant cryptography, photonic integrated circuits, and course options on ethics and technology.

With these offerings and research knowledge, RIT finds itself well poised to help fill the future quantum workforce.

“We continue to develop the coursework in the minor with plans to grow it,” added Zwickl. “Quantum is where things are changing, and there’s a huge opportunity. It is becoming much more accessible for students from different majors, and we have courses at RIT that are part of that shift.”