Microelectronic engineering program founder retires from Kate Gleason College of Engineering

Lynn Fuller has seen industry grow and alumni succeed in global semiconductor companies

A. Sue Weisler

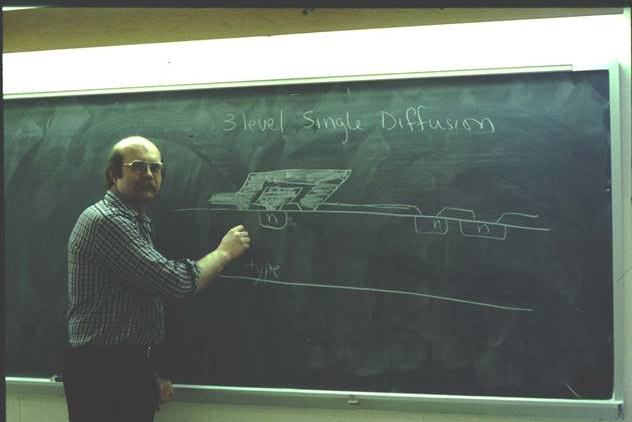

Professor Lynn Fuller, founder of RIT’s microelectronic engineering program, is retiring this June after a distinguished career as teacher, mentor, researcher, and entrepreneur.

President Joe Biden recently called for more resources to bolster the computer chip industry to meet consumer and commercial demands. Lynn Fuller has done more than his share to provide assets for this important industry.

Fuller established the first microelectronic engineering program in the country in 1982 at RIT, and today many program graduates lead efforts at the top microchip firms advising the president.

Evolution of an industry

Lynn Fuller was named one of RIT’s Innovators in 2013 and the video of his work is an overview of both the new microelectronic engineering program and the evolution of an industry. The Dr. Lynn Fuller Endowed Student Support Fund was established this year to commemorate his influence and to provide financial support to continuing his legacy.

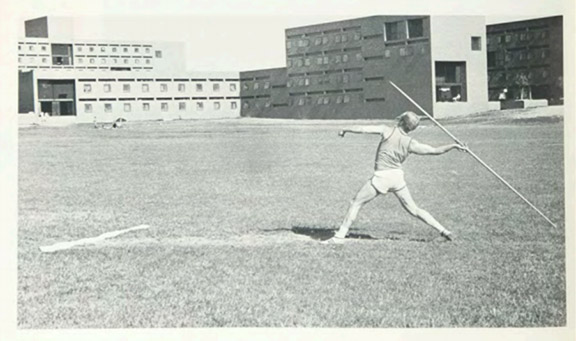

Teacher and mentor define Fuller best. When he formally retires in June, the alumnus of the engineering college will have earned multiple awards and recognitions over a notable career—as RIT’s first NCAA All-American, a two-time Eisenhart honoree for excellence in teaching, an influential program administrator, IEEE Fellow, patent-holder, and inductee into RIT’s Sports Hall of Fame and the university’s Innovation Hall of Fame.

“Microelectronic engineering has provided the manpower for the semiconductor industry since it began 40 years ago. We were the only ones doing that and we have thousands of grads at all of the big companies that are now making microchips,” said Fuller.

Students had comprehensive skills in key areas of building integrated circuits. That distinguished RIT.

“It is done differently here,” he said about the non-traditional degree program that combined chemical, electrical, and mechanical engineering concepts with materials and imaging science. “To create a degree program that combines all of that well and correctly—nobody else has been able to do this.”

Lynn Fuller taught some of the first electronics courses at the university in both the engineering college and through the College of Continuing Education.

Fuller ’70, ’73 (electrical engineering) worked on getting his own doctoral degree, just about the same time he began foundational work to build the microelectronic engineering program. Since the early 1970s and into the 1980s, more computers were being developed and Fuller witnessed a big change in how they were being built.

“I remember as an undergraduate that we didn’t even have transistors at RIT; we had vacuum tubes in our labs. I knew it was going to be a growing field,” he added. “While I was finishing my Ph.D., Texas Instruments came to RIT and asked us to start this program. They saw we can do the lithography and imaging science and we could also make the transistors.”

Texas Instruments (TI) offered to hire every one of Fuller’s graduates, and since that time, many have taken their places in international companies such as TI, Global Foundries, IBM, and Intel.

Fuller gained administrative and financial support for the Semiconductor Manufacturing and Fabrication Laboratory, an extensive clean room where microchips can be fabricated. Located in the Kate Gleason College of Engineering, his students have hands on experience in fabrication.

“Our unique thing was providing engineers to go into the manufacturing side, making the microchips,” he said. “We are still very successful in preparing these engineers for careers in the semiconductor industry. It’s a $450 billion a year industry worldwide, and growing like crazy.”

While there are challenges today regarding resources, Fuller knows firsthand that it is a highly complex, multi-step process to make computer chips, and it takes time and money to build a new plant, sometimes more than 10 years.

Fuller participated in track and field, hockey and football, some of the earliest sports teams at the university. He was RIT’s first All-American.

“It is not just a U.S. problem that Biden can solve, but he can help just by recognizing that this kind of manufacturing is high tech. And we’re really good at here at RIT,” he said. “I’m not worried at all. The biggest take away is the future looks great for RIT graduates. They are going to have jobs in the U.S. and elsewhere.”

In retirement, Fuller plans to complete construction of a cabin in nearby Canandaigua and to spend more time with family, his wife, Oksana ’70 (graphic design), who he met at RIT, their twin daughters and five grandchildren.

“I feel like I received all the accolades that I want,” he said.

Fuller will add “Professor Emeritus” to his list of accomplishments. He was honored with the title recently, a recognition given to faculty who have made a significant mark on college programs and the university overall.