Psychologist revolutionizing addiction, aggression treatments

A leader in the field of family violence prevention is challenging the standard practice for treating offenders in the United States with an alternative that is grounded in science and connects the dots between substance abuse and aggression

A. Sue Weisler

The physician assistant classroom includes 20 practice areas, including three set up like hospital rooms.

Clinical forensic psychologist Caroline Easton ’90 (biotechnology) has shown that addiction and aggression go hand-in-hand and require integrated treatment. Easton, a professor of biomedical sciences in RIT’s College of Health Sciences and Technology, embraces an approach to clinical care that treats the whole person.

Her progressive model of care and emphasis on interactive medical technologies are shaping the college’s behavioral health program, housed in the new Clinical Health Sciences Center.

The facility, operational this fall, consolidates the clinical programs in the College of Health Sciences and Technology, dedicates space for clinical activity in behavioral health and includes a family medicine practice group operated by Rochester Regional Health, a university partner through the RIT & Rochester Regional Health Alliance.

“I don’t believe you can tackle medical health without addressing mental health,” Easton said. “We need to educate the new student about this integrative care model and incorporating technology into it.”

Connecting the dots

Easton, in 2003, founded and directed Yale’s Forensic Drug Diversion Clinic to treat court-referred patients on probation or parole. Her model of care—Substance Abuse-Domestic Violence Behavioral Therapy—treats male criminal offenders who have problems with addiction and aggression. Her method focuses on reducing substance use while building healthy coping skills for handling negative emotions. The client-centered approach is grounded in cognitive behavior theory and has measurable outcomes.

The Substance Abuse-Domestic Violence Behavioral model grew from Easton’s 1998–1999 studies, funded, in part, by the Donaghue Foundation and the National Institute of Drug Abuse, and replicated in 2006 in another randomized controlled trial in Connecticut.

Results of the 2006–2010 trial show that Easton’s method was more effective than another evidence-based addiction treatment in reducing cocaine and alcohol use and aggressive behavior. Three months after the offenders completed the individualized therapy program, the men in the Substance Abuse-Domestic Violence Behavioral Therapy group had significantly reduced amounts of cocaine and alcohol use detected in their toxicology screens and significantly fewer violent episodes than the offenders treated for addiction alone.

“Participants in the control condition had approximately seven violent episodes compared to the Substance Abuse-Domestic Violence group, which had one episode,” Easton reported. “This study underscores that the Substance Abuse-Domestic Violence model, a cognitive behavioral therapy approach, may be an important vehicle for changing two specific maladaptive behaviors—addiction and aggression.”

Easton’s evidence-based approach is an alternative to the “one-size-fits-all” Duluth model. The Duluth Domestic Abuse Intervention Project, established in Minnesota 30 years ago, is the standard therapeutic method practiced around the world. The common court-referred treatment program lumps together offenders of varying severity for anger management treatment without proper screening for mental health and/or substance abuse issues. In most cases, the confrontational model, based on accountability, backfires and leads to high rates of re-offense and relapse, according to Easton.

“When an offender is arrested for family violence and they’re referred into an anger management group, at least 50 percent report a problem with alcohol and drugs,” Easton said. “Likewise, if you evaluate someone coming into an addiction treatment facility, about 50 percent say they have problems with family violence in their home; either they are perpetrating it or they have problems managing their anger. On either side you see the high co-occurrence of addiction and aggression. They go together. I call them two negative peas in a pod.”

Signs of a shift away from the Duluth model and its derivations were seen in 2013 when the Veterans Health Administration of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs prohibited the use of the Duluth Model treatment for veterans. Their multiple and complicated treatment needs require interventions grounded in science that encompass trauma, addiction, psychiatric disorders, traumatic head injuries, medical illness and pain, Easton said.

Behavioral health sciences at RIT

The College of Health Sciences and Technology is in the early stages of exploring graduate degrees in behavioral health sciences around Easton’s research.

Dr. Daniel Ornt, vice president and dean of the Institute and College of Health Sciences and Technology, said with this will come opportunities for collaboration with Rochester Regional Health in clinical psychology.

RIT’s behavioral health program also includes the Center for Applied Psychophysiology and Self-regulation, founded by Dr. Laurence Sugarman, a behavioral pediatrician. His center focuses on helping children and young adults with anxiety and autism spectrum disorder through biofeedback and interactive gaming technology.

Medical interactive technologies like cell phone apps, games for health care and virtual training tools can also be used to enhance positive outcomes in therapies for substance abuse and family violence.

“The use of virtual tools and avatars is the way of the future,” Easton said. “These adjunctive tools can be useful in patient care settings, are non-threatening, are realistic and can pose real-life scenarios and triggers.”

Soon after arriving at RIT in 2012, Easton built a multidisciplinary team to develop interactive digital therapies to help clients reinforce and shape healthy coping skills.

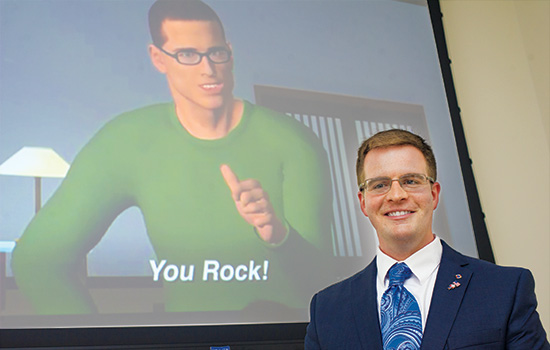

Al-Virt, designed by Alan Gesek ’11, ’14 (illustration, medical illustration) is an avatar coach under construction. When fully realized, Al-Virt 2.0, an upgraded design by Clayton Scavone ’18 (game design), will engage clients in virtual-role playing exercises and model conflict-resolution skills. The cyber coach, a supplementary therapy, will reward behavioral changes with positive words and gestures.

“I feel like a kid in a candy shop because the technology is so readily available here,” Easton said. “I think that’s where RIT can take the lead in behavioral health, because it’s all about technology now. Not all campuses have it. At RIT, you have the computer programmers, the gamers, the medical illustrators and the science behind behavioral health.”

The integration of technology and behavioral health is an expanding field, said Cory Crane, an assistant professor of biomedical sciences.

“Caroline is on the cusp of it,” he said. “Her simulated therapist, Al-Virt, is increasing in functionality. The goal is to get an interactive, realistic experience out of an avatar to keep the patient engaged in between sessions.”

Crane joined the college in 2013. He holds a joint position with RIT and the Veterans Hospital in Canandaigua, where he conducts clinical research on addiction and intimate partner violence.

Reducing domestic violence

According to the World Health Organization, one out of three women has been physically or sexually abused. High percentages are caretakers with children who witnessed or were involved in the dispute.

“Research has shown that those children—if they don’t get the treatment they need—are likely to become an offender or a victim and resort to early drug use as a coping skill for what they saw being done in their family,” Easton said.

Family violence is a breeding ground for addiction, mental health and medical problems, she said. “It is no different than a contagious disease within a family. If we can treat and prevent the chaos, drug use and the verbal and/or physical aggression, then we can help.”

The Monroe County Office of Mental Health in New York last year piloted Easton’s Intimate Partner Violence Blueprint to reduce future episodes of domestic violence and related criminal offenses. The coordinated effort was implemented at four designated treatment sites in the Rochester area.

Rollout of Easton’s IPV Blueprint was a three-year effort. It began with the up-hill battle of convincing local stakeholders in the courts system, mental health and chemical dependency service providers and local advocacy groups to adopt an integrated model of care with measurable outcomes.

Easton and Crane provided training, supervision and continued oversight of clinical staff and supervisors during transition to the integrated model of care for addiction and family violence. The “evidence-based” aspect of the treatment model requires clinical staff to consistently interview patients and document behavioral change.

Central to the program is a screening tool for family violence Easton designed for the courts and treatment facilities. Offenders with substance dependency are diagnosed and provided a coordinated and systematic model of care that teaches them to decrease substance abuse and achieve abstinence while developing healthy coping skills for controlling negative emotions.

“I think therapists hesitate to ask clients about embarrassing behaviors, such as, ‘Do you yell, scream, hit?’” Easton said. “But if we’re not screening for aggression, then they’re likely not going to get treatment for it.”

A growing reputation

Several alcohol and substance abuse clinics in London have used Easton’s treatment therapy in their programs for years. Colleagues in Brazil have expressed interest in adapting the therapy for the Latino culture.

Easton’s reputation in her field has grown since she built her professional reputation at the Forensic Drug Diversion Clinic at Yale School of Medicine. Now her challenge to the standard model of care has gone full circle with a study she conducted for the Connecticut General Assembly from August 2014 to September 2015. Her findings have led to revisions to family violence policy and procedure in the state hard hit by the Sandy Hook Elementary School shootings and subsequent high-profile cases involving children killed in family violence episodes.

Easton, in September, briefed the Connecticut Public Health Division and State Legislature on recommended changes in policy and allocation of funding for treatment protocols and prevention efforts for offenders of intimate partner violence based on the 165-page report, “Addressing Family Violence in Connecticut: Strategies, Tactics and Policies.”

Easton was invited to lead the study initiated by the Connecticut General Assembly Public Health Committee to target common causes of violence and develop prevention strategies for pilot projects. She served as study manager for the nonprofit Connecticut Academy of Science and Engineering.

She is hopeful that New York will adopt Connecticut’s stance.“Connecticut is progressive and their models of care are usually followed by other states.”

Read more

RIT professors Caroline Easton ’90 and Cory Crane are changing how behavioral health clinicians think about and treat addiction and intimate partner violence. A. Sue Weisler

RIT professors Caroline Easton ’90 and Cory Crane are changing how behavioral health clinicians think about and treat addiction and intimate partner violence. A. Sue Weisler The new Clinical Health Sciences Center is designed with space for RIT’s new thrust in behavioral health and focus in health and wellness. The 45,000-square-foot space provides room for Caroline Easton ’90 to expand her research and includes a physician office operated by Rochester Regional Health. A. Sue Weisler

The new Clinical Health Sciences Center is designed with space for RIT’s new thrust in behavioral health and focus in health and wellness. The 45,000-square-foot space provides room for Caroline Easton ’90 to expand her research and includes a physician office operated by Rochester Regional Health. A. Sue Weisler Alan Gesek worked with Caroline Easton and a multidisciplinary team of faculty and students to design the digital coach Al-Virt to promote healthy coping skills for people struggling with addiction and aggression. A. Sue Weisler

Alan Gesek worked with Caroline Easton and a multidisciplinary team of faculty and students to design the digital coach Al-Virt to promote healthy coping skills for people struggling with addiction and aggression. A. Sue Weisler