RIT Astronomer Mines Spitzer Space Telescope Data for Massive Starbursts

Dan Dicken studies heat energy from distant active galaxies

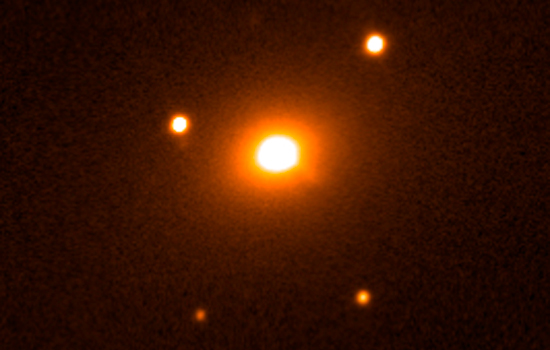

Although the central object looks like a star, this is actually a picture of the heat energy generated from the black hole in an AGN galaxy 726 million light years away. (Image provided by Dan Dicken.)

Understanding the evolution of galaxies is one of the biggest questions confronting astronomers today. Looking at distant astronomical objects gives scientists important clues to the origins of the Milky Way Galaxy and other galaxies in the local universe.

One question concerning Dan Dicken, a post-doctoral research scientist at Rochester Institute of Technology, pertains to the origin of infrared emission from powerful distant active galactic nuclei. AGN galaxies are the brightest class of galaxies in the universe and are powered by supermassive black holes at their centers. Stars and other interstellar matter are caught in the immense gravitational field of the central supermassive black hole and are ripped apart radiating vast amounts of energy in the process.

“What makes active galactic nuclei so special is they are incredibly bright galaxies—the brightest—not only at optical wavelengths, but at all wavelengths from radio all the way through to X-rays,” Dicken says. “This means they can be seen at very large distances and are, consequently, important for the evolution of the universe.”

Active galactic nuclei are rich in gas and dust that feed the massive black hole but also obscure it from view. The dust absorbs visible light from the hidden central black hole and re-emits it as infrared waves.

“Like infrared cameras on earth, infrared astronomy views the universe at wavelengths we associate with heat energy,” Dicken says. “We can’t see infrared wavelengths, but we can feel them as heat from things like radiators. The great power of infrared astronomy is that it’s not obscured like optical astronomy. You can see the heat energy from the central source. You can see through the dust.”

Dicken will interpret the infrared radiation by mining the huge public archive of data collected by NASA’s infrared Spitzer Space Telescope. This telescope completed its first mission phase in May when its essential coolant, needed for the most sensitive observations, ran out.

Having only finished his doctorate degree six months prior, Dicken won a $100,000 grant from NASA to support the study and employ a student assistant.

“Winning such a prestigious award at the beginning of my career as an astronomer is phenomenal for me,” he says. “And it serves to show that if you have the backing of such an experienced team, such as the staff and faculty at RIT, you can really turn a good idea into a full-sized science project.”

A key aspect of Dicken’s study is to understand the radiation emitted from massive starbursts. The energy radiated from massive star formation can also heat the dust that radiates from AGN at infrared wavelengths. However, because of the vast distances to these objects it is impossible to directly separate the two possible heating sources—a starburst or the central supermassive black hole.

“The big question I’d like to answer is to determine the proportion of starbursts to active galactic nuclei heating of dust and gas in distant AGN,” Dicken says.

Identifying the signatures of starbursts—through the detailed analysis of infrared spectra—is one technique Dicken will use to sift through the reams of Spitzer data. Emissions from distant starbursts contain the same organic molecules (Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons) observed in starbursts in local galaxies. This information creates a blueprint for differentiating starbursts from supermassive black holes associated with active galactic nuclei.

Dicken’s study will also help scientists understand more about the co-evolution of supermassive black holes and their host galaxies. Current theories about galaxy evolution predict that galaxy mergers produce gas flows, which trigger starbursts and active galactic nuclei.

“One of the big problems of understanding how active galactic nuclei work is that the gas and dust in the galaxy rotate around the galaxy just as planets do around the Sun, and you have to do something to that gas to make it fall in,” says Andrew Robinson, associate professor of physics and director of RIT’s Astrophysical Sciences and Technology graduate program. “Galaxy mergers are thought to play an important role in this: When you smash two galaxies together individual stars don’t collide, but the gas does, causing it to lose energy and fall inward.”

Dicken’s research also could help resolve how many different types of active galactic nuclei exist. Because they are located so far away AGN appear as point sources, like stars, in images. Scientists study the structure of AGN by inference and by secondary effects.

The observed properties of AGN vary widely, suggesting many different types. According to a popular theory, the galaxies only appear different because of the perspective at which they are “viewed.” In this theory, most of the dust and gas surrounding the AGN is in the form of a thick disk, or torus. When viewed edge-on, it hides the central black hole and its surrounding emission regions at visible wavelengths; however, when viewed face-on astronomers see the “central engine” directly.

“A goal of active galactic nuclei astronomy is to unify these objects, because we think they are basically the same,” Dicken says. “As infrared wavelengths are not obscured by dust like optical emission, this Spitzer data is a great resource for testing whether these are indeed the same objects and testing our unification hypothesis.”

Scientists on Dicken’s team include Andrew Robinson, associate professor of physics at RIT; David Axon, research professor at RIT and head of the School of Mathematics and Physical Sciences at University of Sussex; Stefi Baum, director of RIT’s Chester F. Carlson Center for Imaging Science; Chris O’Dea, professor of physics at RIT; Clive Tadhunter, professor of astrophysics at University of Sheffield; and Alessandro Capetti, associate astronomer at the Astronomic Observatory of Torino.