RIT experts help make computing accessible

Caring About Education: RIT Professor Matt Huenerfauth is investigating new ways to teach accessibility to computing students, including supporting research teams that have both hearing and deaf students working together.

RIT’s student and faculty researchers are working to make technology accessible for all by changing the culture of computing.

In Someone Else’s Shoes

A new smartphone or computer program is supposed to improve a person’s life and make it easier. But for the more than 1 billion people around the world who have some form of disability, it can sometimes feel more like a barrier.

“Computing accessibility becomes a problem when, for example, apps aren’t designed with features for those who are deaf and hard of hearing or if some website can’t be used because you are blind,” said Matt Huenerfauth, professor in the Department of Information Sciences and Technologies at RIT. “There’s a lot of examples out there, but it certainly doesn’t have to be that way.”

At RIT, student and faculty researchers are working to change the culture of development in an effort to make technology accessible for all.

The group hopes to do this by creating new technologies of their own that incorporate computing accessibility and people with disabilities throughout the design and development process. Experts are also changing the future of accessible computing by evolving education and the way that future developers are taught.

Coming together in RIT’s Center for Accessibility and Inclusion Research, or CAIR (pronounced “care”), researchers are working on everything from motion-capture technologies to produce linguistically accurate animations of American Sign Language to new pedagogies for teaching accessibility. Created in 2015 in RIT’s B. Thomas Golisano College of Computing and Information Sciences, the center is now home to more than 25 faculty and students looking to make a difference.

“Computers, smartphones, and the internet have become essential for communicating and getting a job, but there are a lot of people potentially being left out,” said Vicki Hanson, a distinguished professor of information sciences and technologies at RIT and co-director of CAIR. “This is a great opportunity for RIT/NTID to tap into its diverse and longstanding culture of accessibility.”

With computing accessibility, the goal is for technology creators to put themselves in other people’s shoes and understand the perspective of people they are designing for. This comes naturally in the center, as several of the researchers have disabilities themselves.

Even the setup of the CAIR lab has accessibility in mind. The room has circular gathering spaces and transparent glass walls that provide line-of-sight for users of ASL and designated wide access paths for wheelchair users. Regardless of ability, it’s important that people with disabilities are participating in the design process, so they can contribute their firsthand perspective when creating technology that benefits everyone.

“When you’re creating any technology, you should ask ‘what do real human users need and want out of this?’” said Huenerfauth, who is also co-director of CAIR. “But your users are not always like yourself and that’s really important for designers to realize.”

Throughout the creation process, RIT experts are also implementing elements of user-centered design. This process is an important part of the undergraduate and graduate human-computer interaction programs at RIT and is based around the idea that the user is the most important source of information.

“The user is at the center of everything we create,” Huenerfauth said. Working from the ground up, RIT researchers are hoping to make the computing world a more inclusive and universally accessible space.

How to Teach Accessibility

For Huenerfauth, the introductory computing classes at RIT have become a little laboratory. As part of a nearly $450,000 National Science Foundation grant, he and Hanson are exploring the best practices for training future computing professionals about inclusive technology development.

While many computing professionals want their work to be accessible to all, it’s typically not something that is explicitly taught in the classroom. Students may not have the chance to work with someone with a disability, and equal access is not always addressed as part of the ethics curriculum.

To address this gap, the RIT team is investigating the efficacy of multiple educational interventions on accessibility. Focusing on undergraduate human-computer interaction courses, Huenerfauth and other instructors are modifying classes to see what moves the needle and gets students thinking about accessibility.

“We might add an activity where students learn how to read braille or a day where students interact with a blind or deaf guest who visits the class,” said Huenerfauth. “Throughout this long-term study, we hope to see how effective different pedagogies are at getting students to apply accessibility within their work.”

In the future, Huenerfauth and Hanson plan to share their findings and help faculty replicate these inter–ventions at other universities.

For Kristen Shinohara, an assistant professor in RIT’s Department of Information Sciences and Technologies who is also researching accessibility pedagogy, the key is to think about accessibility from the beginning—and not simply as a means of compliance.

Since 1998, the section 508 amendment to the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 has required federal agencies to make their electronic and information technology accessible to people with disabilities. In recent years, many other organizations, including Google and Microsoft, have also made commitments to include accessibility in their products.

“Right now, many designers are conditioned to think of accessibility as an afterthought or add-on,” said Shinohara. “We need them to believe in these ideas and incorporate them from the beginning of the design process.”

To help change the thought process, Shinohara is developing a set of method cards used to get designers thinking about accessibility. For example, a card might prompt the designer to think about situations where a visually impaired person might use a screen reader. Will they want to use a speech synthesizer in public or might they prefer using a braille display?

“Oftentimes, it’s important to think about the social setting and functionality of accessibility features,” said Shinohara. “I hope to make it easier for designers to incorporate accessibility compliance, so they don’t think of it as a burden and so they can see the benefits.”

Perceiving the World Differently

Taylor Gotfrid, a human-computer interaction graduate student at RIT, embraces the importance of accessibility research and is working to better understand the ways that people with cognitive disabilities interact with smart technology.

“Technology has the potential to improve so many people’s lives in different ways,” said Gotfrid, who is from Santa Rosa, Calif. “It would be unkind not to think about people with disabilities.”

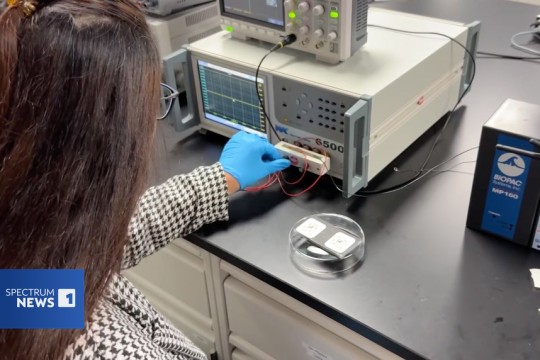

Gotfrid and Shinohara are researching how adults with autism interact with e-textiles—fabrics and clothing that have digital components, including batteries, lights, sensors, and other electronics embedded in them. Through the project, they hope to create a framework that can be used by developers creating products that may be used by those on the autism spectrum.

“You might think that everyone knows how to use a toy car a certain way, but researchers have observed that people with autism might flip the car over and just play with the wheels,” said Shinohara. “Similarly, adults with autism might perceive and interact with e-textiles in different ways than we expect.”

Collaborating with Annuska Zolyomi, an information sciences Ph.D. student at the University of Washington, the team plans to conduct an exploratory workshop. By observing how adults with autism play with different buttons, lights, and e-textile objects, Gotfrid hopes to see what participants like and what they get frustrated with. She also wants to know how different materials affect the way an item is used.

Zolyomi plans to use e-textiles in a weighted blanket that helps people with autism relieve stress. Touch-activated lights embedded in the blanket can be used in conjunction with breathing exercises that help reduce anxiety.

“We want to learn how a person would intuitively know to press a certain spot of the e-textile to make the lights turn on,” said Gotfrid. “People perceive the world differently, so we need to include them in the process to make sure these technologies are actually useful for them.”

Participatory Design

Many ideas for accessibility projects stem from real-life problems that students and faculty encounter on a daily basis.

“As someone who is deaf, I personally understand the need for communication and oftentimes feel frustrated by the lack of access,” said Larwan Berke, a computing and information sciences Ph.D. student from Fremont, Calif., who is working in CAIR. “It is my goal to help deaf people have greater accessibility in various places.”

Berke is part of an interdisciplinary team researching how automatic speech recognition (ASR) captioning technologies can be used by deaf people in one-on-one meetings with hearing individuals. Collaborating on the project are students in CAIR and at NTID; Huenerfauth; and NTID researchers Michael Stinson, Lisa Elliot, James Mallory, and Donna Easton.

Throughout the evolving project, the group has developed an app that integrates ASR into instant messaging on a smartphone or computer. This technology allows for two-way conversations, where deaf and hard-of-hearing people can type out and read responses, while hearing colleagues speak into the device.

However, ASR technology is known to be imperfect and deaf users often have to cope with errors in the captioning. Berke is investigating ways to alter the display style of the captioning, based on how confident the ASR technology is in its output.

Adding onto the work, Huenerfauth and Sushant Kafle, a computing and information sciences Ph.D. student in CAIR, are inventing a new metric for automatically evaluating the accuracy of ASR. The technology allows a user to know when they can’t fully trust certain words in the captions.

“We conducted experiments to determine whether our metric matched the judgments of deaf and hard-of-hearing users, as to which automatically produced captions were understandable,” said Kafle, who is from Nepal. “In the future, we will continue to investigate variations on this metric and evaluate them in experiments with deaf and hard-of-hearing users.”

For RIT accessibility researchers, the key to this and any project is including real users and those with disabilities throughout the entire design process.

“It’s easy to be wrong when you’re just imagining what another group of people needs out of a piece of technology,” said Huenerfauth. “Ideally, development teams of the future are going to continue being more diverse and more inclusive.”