Students, faculty respond creatively to online learning

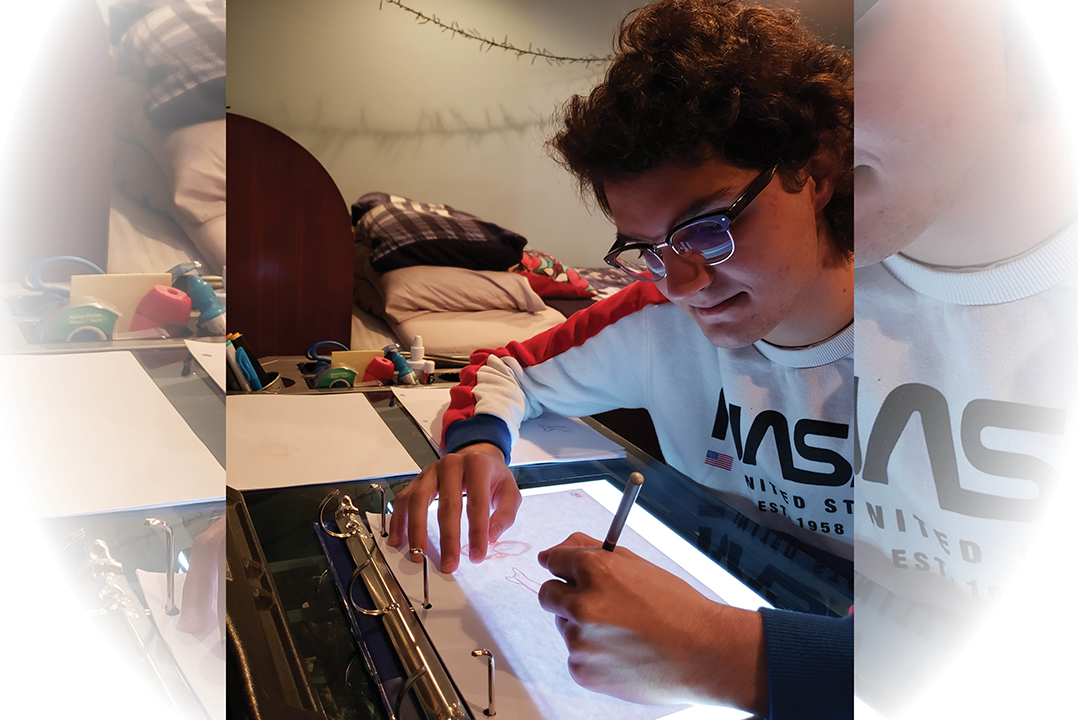

Nick Passanese, a Film and Animation student, draws on a do-it-yourself light table he made at home in support of coursework for his Principles of Animation class.

On March 23, all courses at RIT went to remote delivery modes. The College of Art and Design, a family of creative thinkers, artists, educators, designers and crafts people, have risen to the challenge and are actively engaged in their coursework. Whether it is taking the studio into their homes or remotely connecting to the vast technology resources found in our labs and across the RIT campus, our students are learning and developing phenomenal work. Our faculty have been phenomenal in transitioning their courses and working with students and academic resources across the RIT campus and around the world. Our partners like Adobe, Autodesk, Avid, Frame.io, Red Giant, Toon Boom Harmony and others have helped to bring software solutions to our students. Below are just a few success stories of our College of Art and Design faculty and student ingenuity and creativity.

As students in an RIT Animation class shifted from learning in labs to their own homes in response to the coronavirus pandemic, creative problem solving ensured a smooth transition.

Assistant Professor Mari Jaye Blanchard’s Principles of Animation class constructed do-it-yourself solutions using standard household items to replace tangible equipment accessible only on campus. It represents one of many innovative teaching and learning examples from RIT’s College of Art and Design as the pandemic forced courses online.

Blanchard created how-to videos for students to seamlessly continue animating if they don’t own the equipment used at RIT. The tutorials focus on how to quickly make light tables to draw on and a downshooter to film individual frames and produce an animation.

One of the light table solutions is a system that holds paper together with a peg bar or three-ring binder and is affixed to a backlit picture frame nailed to a mount. A similar concept features drawing on the fastened pages against a window.

To animate the drawings, Blanchard suggested creating a DIY downshooter requiring as little as a cutting board nestled on a stack of books and a rubber band to secure a smartphone to the board. With the phone’s camera positioned downward at the drawings, individual photos can be taken and grouped into a video in a stop motion app.

“From translucent storage containers with portable lights and usefully positioned pre-existing glass shelves to entire homemade light boxes resting on paint cans, these School of Film and Animation students embraced the challenge with glowing results,” Blanchard said.

Below are other creative ways course content is being delivered virtually.

Design challenge

RIT Graphic Design Assistant Professor Keli DiRisio launched the #RITgdchallenge2020 on Instagram to foster community and fun during difficult times. The challenge is optional for students and, DiRisio said, is meant to “remind them why we love design” and forget about stress.

Students produce designs around a weekly prompt and post their creations to Instagram using the hashtag.

Thinking through glass

An elective course taught by Suzanne Peck, lecturer in the Glass program, is employing “glass-based thinking” in the absence of the hot shop facility.

“We’re opening up curiosity and going to learn about this material in other ways,” Peck said.

The class started an Instagram account to share its output and remain connected. Weekly assignments task students with thinking about the use of glass while not having access to it, and posting their results on Instagram.

The first prompt, “reflection,” challenged students to capture their emotions through self-portraits taken in glass or reflective surfaces. The second assignment centered on designing experimental glass vessels with paper and scissors, and then translating them from 2D to 3D.

The class consists of seven students from Industrial Design and one from New Media Design.

“It might be an interesting way for the RIT community to see how we think about glass,” Peck said of the remainder of the course. “If we don’t have a hot shop, can we still be artists? And the answer, of course, is yes. You don’t have to have access to a material to think through that material. Art is as much concept and philosophy and mining your own creative impulses as it is being in the studio with your hands busy.”

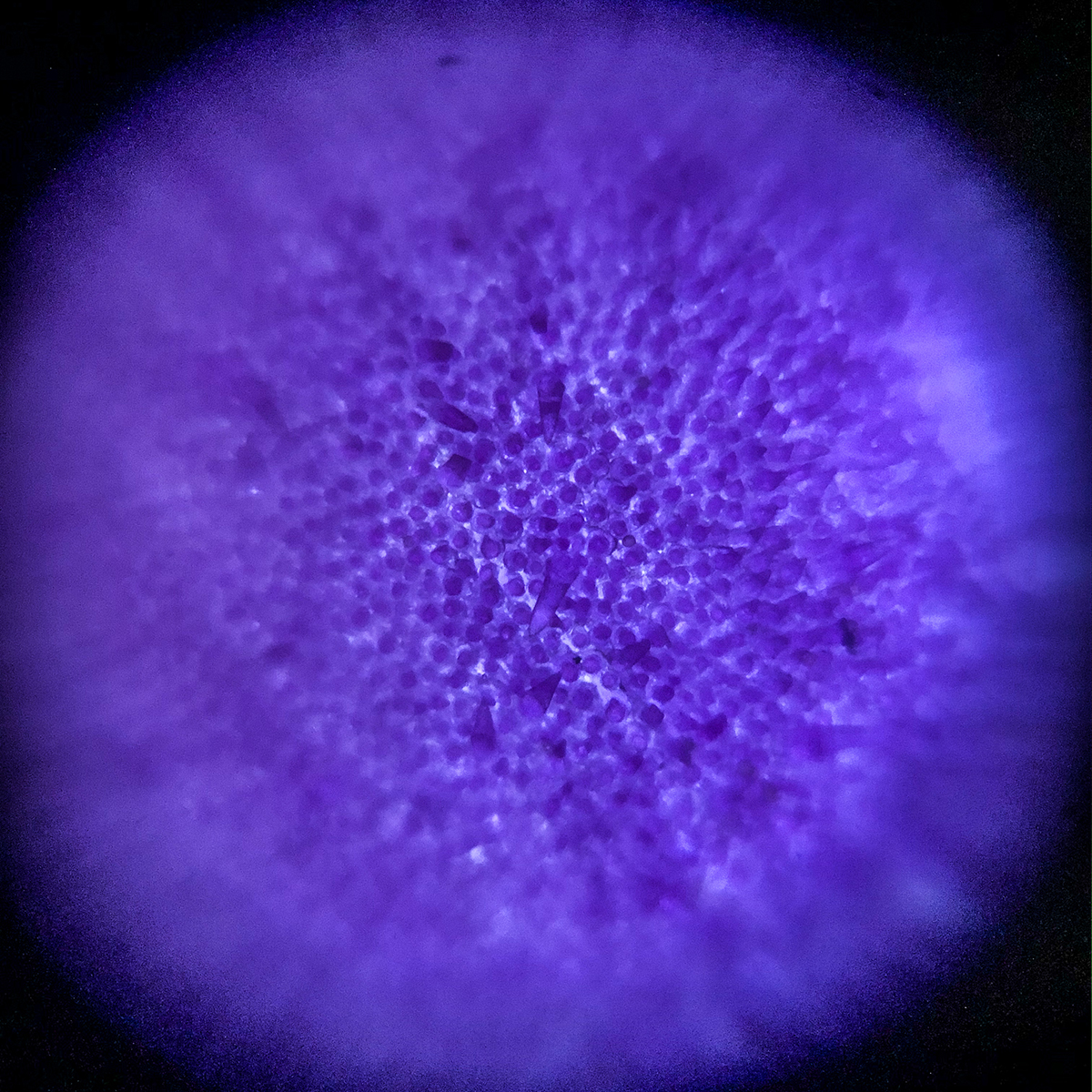

Paper problem-solving

Michael Peres, professor and associate chair of the School of Photographic Arts and Sciences, employed a low-cost, yet highly effective solution in his Magnified Imaging class.

Without access to microscopes, students are using Foldscopes — paper microscopes that can capture smartphone images at 140x magnification — to complete microscopy projects.

It’s a substantial pivot for students, who, Peres said, went from operating equipment worth $250,000 to the Foldscopes.

“They know what high quality is so we are excited to evaluate and optimize our new microscopes,” Peres said. “I explained to the class that it is their job to invent ways to make the best, and consistent, outcomes given the limitations and quality of a paper instrument and its $1 optics.”

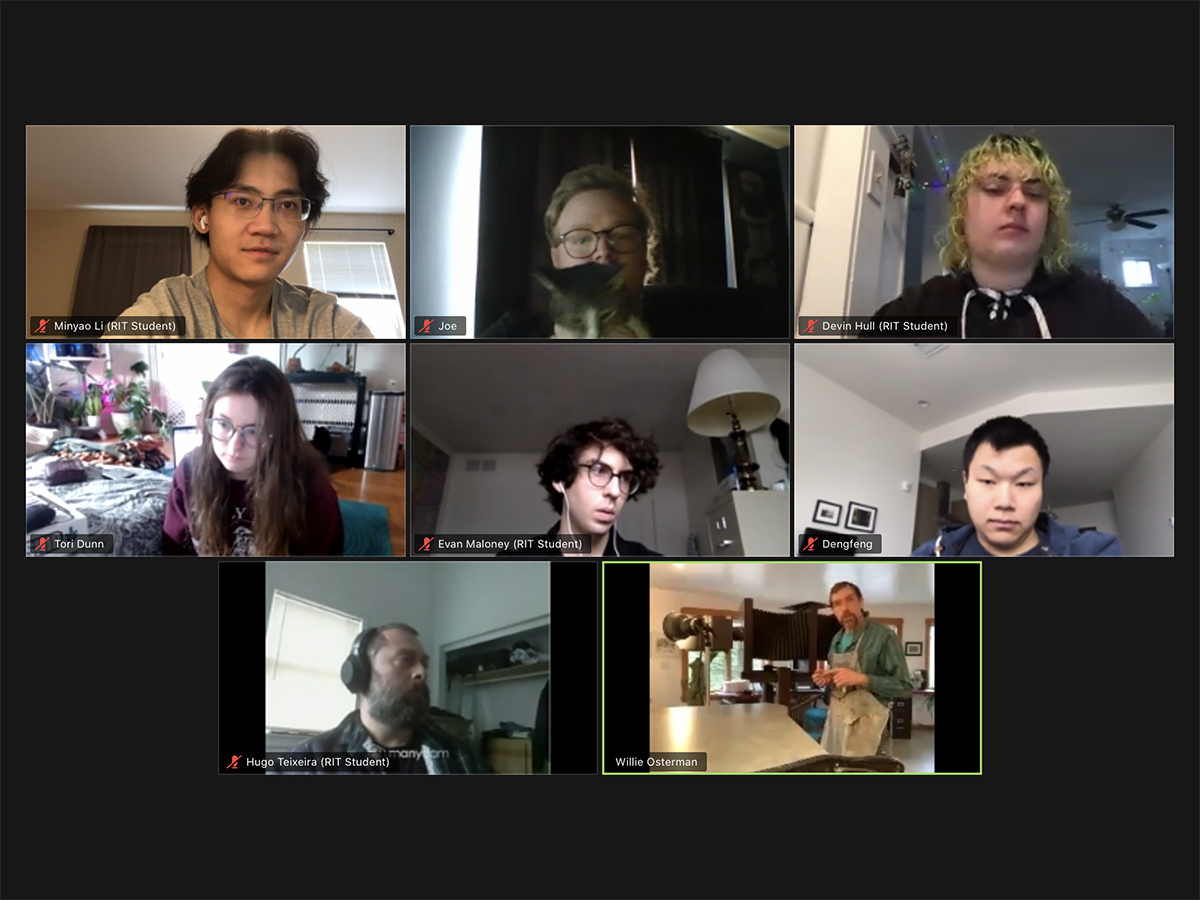

Connecting with industry

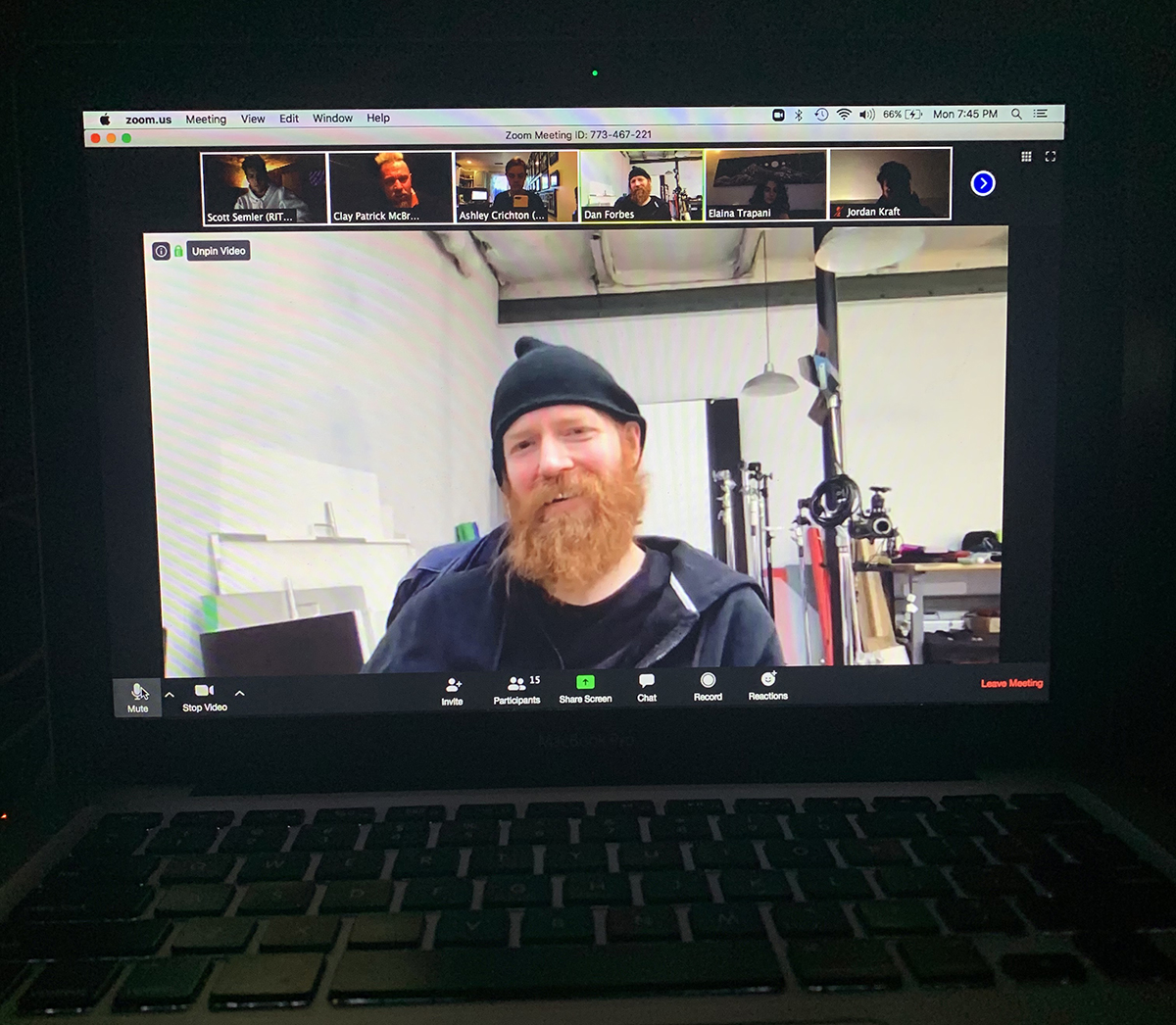

Elsewhere in RIT’s photography school, Advertising Photography Senior Secturer Clay Patrick McBride is keeping students connected with industry via Zoom. He is inviting professionals to speak to his Portfolio Development class on the video conferencing platform.

Guest speakers have included producer/owner of location scouting company Where’bouts, Inc. Mark Bodnar and renowned photographers Dan Forbes and Frank Ockenfels 3.

Observation learning

In place of students working hands-on in a lab, photography Professor Willie Osterman is teaching the wet-plate collodion process through online demos from his home studio.

The complicated process is an early form of photography that requires the use of a darkroom.

“The first half of the semester was an intro to the process where they actively worked and practiced,” Osterman said of the class for undergraduate and graduate students. “The intent for the second half was for them to evolve their practice and knowledge. As we are unable to evolve their practice, they will expand their knowledge by observing me at work in my studio and then researching and discussing.”