Study explains decades of black hole observations

RIT scientist’s simulation code takes ‘snapshots’ of the X-ray spectra

Scott Noble, associate research scientist in RIT’s Center for Computational Relativity and Gravitation

A new study by astronomers at NASA, Johns Hopkins University and Rochester Institute of Technology confirms long-held suspicions about how stellar-mass black holes produce their highest-energy light.

“We’re accurately representing the real object and calculating the light an astronomer would actually see,” says Scott Noble, associate research scientist in RIT’s Center for Computational Relativity and Gravitation. “This is a first-of-a-kind calculation where we actually carry out all the pieces together. We start with the equations we expect the system to follow, and we solve those full equations on a supercomputer. That gives us the data with which we can then make the predictions of the X-ray spectrum.”

Lead researcher Jeremy Schnittman, an astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, says the study looks at one of the most extreme physical environments in the universe: “Our work traces the complex motions, particle interactions and turbulent magnetic fields in billion-degree gas on the threshold of a black hole.”

By analyzing a supercomputer simulation of gas flowing into a black hole, the team finds they can reproduce a range of important X-ray features long observed in active black holes.

“We’ve predicted and come to the same evidence that the observers have,” Noble says. “This is very encouraging because it says we actually understand what’s going on. If we made all the correct steps and we saw a totally different answer, we’d have to rethink what our model is.”

Gas falling toward a black hole initially orbits around it and then accumulates into a flattened disk. The gas stored in this disk gradually spirals inward and becomes compressed and heated as it nears the center. Ultimately reaching temperatures up to 20 million degrees Fahrenheit (12 million C) — some 2,000 times hotter than the sun’s surface — the gas shines brightly in low-energy, or soft, X-rays.

For more than 40 years, however, observations show that black holes also produce considerable amounts of “hard” X-rays, light with energy 10 to hundreds of times greater than soft X-rays. This higher-energy light implies the presence of correspondingly hotter gas, with temperatures reaching billions of degrees.

The new study bridges the gap between theory and observation, demonstrating that both hard and soft X-rays inevitably arise from gas spiraling toward a black hole.

Working with Noble and Julian Krolik, a professor at Johns Hopkins, Schnittman developed a process for modeling the inner region of a black hole’s accretion disk, tracking the emission and movement of X-rays, and comparing the results to observations of real black holes.

Noble developed a computer simulation solving all of the equations governing the complex motion of inflowing gas and its associated magnetic fields near an accreting black hole. The rising temperature, density and speed of the infalling gas dramatically amplify magnetic fields threading through the disk, which then exert additional influence on the gas.

The result is a turbulent froth orbiting the black hole at speeds approaching the speed of light. The calculations simultaneously tracked the fluid, electrical and magnetic properties of the gas while also taking into account Einstein’s theory of relativity.

Running on the Ranger supercomputer at the Texas Advanced Computing Center located at the University of Texas in Austin, Noble's simulation used 960 of Ranger’s nearly 63,000 central processing units and took 27 days to complete.

Over the years, improved X-ray observations provided mounting evidence that hard X-rays originated in a hot, tenuous corona above the disk, a structure analogous to the hot corona that surrounds the sun.

“Astronomers also expected that the disk supported strong magnetic fields and hoped that these fields might bubble up out of it, creating the corona,” Noble says. “But no one knew for sure if this really happened and, if it did, whether the X-rays produced would match what we observe.”

Using the data generated by Noble’s simulation, Schnittman and Krolik developed tools to track how X-rays were emitted, absorbed and scattered throughout both the accretion disk and the corona region. Combined, they demonstrate for the first time a direct connection between magnetic turbulence in the disk, the formation of a billion-degree corona, and the production of hard X-rays around an actively “feeding” black hole. Results from the study, “X-ray Spectra from Magnetohydrodynamic Simulations of Accreting Black Holes,” were published in the June 1 issue of The Astrophysical Journal (ApJ, 769, 156).

In the corona, electrons and other particles move at appreciable fractions of the speed of light. When a low-energy X-ray from the disk travels through this region, it may collide with one of the fast-moving particles. The impact greatly increases the X-ray’s energy through a process known as inverse Compton scattering.

“Black holes are truly exotic, with extraordinarily high temperatures, incredibly rapid motions and gravity exhibiting the full weirdness of general relativity,” Krolik says. “But our calculations show we can understand a lot about them using only standard physics principles.”

The study was based on a non-rotating black hole. The researchers are extending the results to spinning black holes, where rotation pulls the inner edge of the disk further inward and conditions become even more extreme. They also plan a detailed comparison of their results to the wealth of X-ray observations now archived by NASA and other institutions.

Black holes are the densest objects known. Stellar-mass black holes form when massive stars run out of fuel and collapse, crushing up to 20 times the sun’s mass into compact objects less than 75 miles (120 kilometers) wide.

Video caption: This animation of supercomputer data takes you to the inner zone of the accretion disk of a stellar-mass black hole. Gas heated to 20 million degrees Fahrenheit as it spirals toward the black hole glows in low-energy, or soft, X-rays. Just before the gas plunges to the center, its orbital motion is approaching the speed of light. X-rays up to hundreds of times more powerful (“harder”) than those in the disk arise from the corona, a region of tenuous and much hotter gas around the disk. Coronal temperatures reach billions of degrees. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

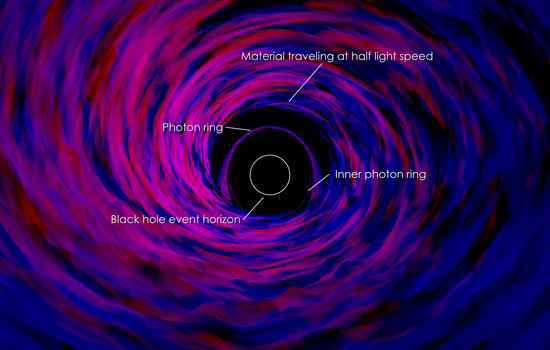

This annotated image labels several features in the simulation, including the event horizon of the black hole.

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

This annotated image labels several features in the simulation, including the event horizon of the black hole.

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center