All-female racing team builds community and a car

Chris Coe

Hot Wheelz co-leader Maura Chmielowiec, a fifth-year mechanical engineering student, was one of the first students to join the team five years ago.

When RIT students arrive at the Formula Hybrid competition at the New Hampshire Motor Speedway in May, they will make history.

The 38 women will be the first and only all-female team at the event, hosted by the Thayer School of Engineering at Dartmouth College. They will compete in the electrical division against universities such as Georgia Institute of Technology, Tufts, Yale and Princeton in a single-seat electric racecar that they built from the ground up.

The undergraduate students are doing all of the engineering, welding and sourcing of components by themselves, as well as negotiating sponsorship deals, crowdsourcing and making a project management plan.

But their story is bigger than one competition. Participants in the 5-year-old team have landed co-ops and full-time jobs. The effort has helped blossom RIT’s partnership with companies, enriched the curriculum, encouraged multidisciplinary learning and strengthened ties with alumni.

And it is helping women break into an industry where they hold only about 25 percent of the jobs, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“I hope they understand how big of an accomplishment it is just getting to the competition,” said Alba Colón, program manager at General Motors and lead engineer for Chevy Racing, which is behind NASCAR stars Jeff Gordon, Danica Patrick and Dale Earnhardt Jr. “Little girls are going to say, ‘one day I want to do that. I want to be like them.’ What they are doing is a big deal.”

Making a team

When then-director of Women in Engineering at RIT Jodi Carville ’83 (industrial engineering) heard that President Bill Destler was adding an electric vehicle dragster race to the 2012 Imagine RIT: Innovation and Creativity Festival, she thought that the female engineering students would enjoy a hands-on activity outside of their classes.

Carville pitched the idea of an all-female team to Harvey Palmer, dean of the Kate Gleason College of Engineering, who gave his support. She then sent an email to students to see who might be interested.

Maura Chmielowiec, a first-year mechanical engineering major at the time, was one of the first to respond. Chmielowiec fell in love with cars when she was 12 years old. She had won a contest through her local hardware store for an all-access NASCAR extravaganza at Watkins Glen, N.Y.

“I was mesmerized,” remembers Chmielowiec, who grew up in Batavia, N.Y. “The smells, the sounds, and watching everyone put the cars together. That is when I ultimately knew what I wanted to do.”

By the age of 14, Chmielowiec had purchased a junky sports car, a black 1986 Nissan 300ZX, for $2,200 with money she made mowing lawns. She didn’t know much about cars but her dad gave her a set of mechanics books and she would read them every day after school. The car was running by the time Chmielowiec could drive.

She was one of about 10 women who volunteered for the project and one of five who did the majority of the work. Carville recruited Kathleen Lamkin-Kennard, a mechanical engineering associate professor, and Martin Schooping, senior project manager for the Center for Integrated Manufacturing Studies

and the New York State Pollution Prevention Institute, to help with the project, and she began raising the meager funds

they needed for the job.

They borrowed Lamkin-Kennard’s son’s combustion go-cart and converted it to an electric vehicle. Schooping, who ran a part-time snowmobile business with his father and brother when he was 8 years old and had participated in past Imagine challenges involving an electric trike, became the technical adviser.

The women came up with a team name, Hot Wheelz, and had a graphic design student create a logo.

On May 5, 2012, the freshman Chmielowiec drove the hot pink car 100 meters in just under six seconds to win the e-dragster race. “The car was designed to do one thing and that was go fast,” Lamkin-Kennard said.

Chmielowiec said she was picked to drive because she was the most confident behind the wheel. The car was a bit on the dangerous side because it was controlled only with an on/off switch. Chmielowiec had to glide to a stop.

“We learned that we needed other safety mechanisms in the car, like brakes,” Carville said, laughing.

More importantly, they learned that Hot Wheelz had all the ingredients to become something special.

The next level

Destler changed the Imagine race the following year to an e-durance challenge. Teams had to buy a new or used children’s electric toy vehicle and modify it to become a competitive e-vehicle. The winner of this race was the team with the most laps completed during the allotted time.

The Hot Wheelz team modified a children’s Power Wheels Escalade and Chmielowiec took the wheel again. The team came in third place overall out of 15 teams and won the event’s innovation award. The real win, though, was an increase in participation to close to 20 women.

One of the new recruits was Jennifer Smith, then a second-year mechanical engineering student from Sidney, Maine, who grew up watching her father restore old cars. Smith joined because she was looking for a hands-on engineering activity. She learns more by doing rather than by reading a textbook, she said. She stayed because she liked the mentorship from the older girls.

Mentorship has always been the key ingredient for the team, Carville said. The younger girls rely on the older students to help them design and build the car and to help them with their schoolwork, from homework to picking classes. All team members play a hands-on role and the team leaders make it a priority to create a risk-free environment.

“It’s not just about building a car, it’s building a sense of community,” Carville said.

Although Smith had only been on the team for a year, she took on a big role for the 2014 campus race. Team leader Chmielowiec was on co-op at GE Aviation in Jacksonville, Fla. Smith, who was one of the few returning members and one of the older students on the team as a third year, became a co-lead.

The competition that year was an e-vehicle autocross challenge, a combination of speed and endurance. Hot Wheelz found a go-cart on Craigslist, took it apart and modified it

for the electric competition.

The team, with Smith as the driver, came in third out of 12 participants.

“Being able to drive was a great experience—to be able to test all of your hard work,” Smith said. “It was a learning experience for me but also really rewarding.”

A different direction

The team’s plans to continue racing on campus were detoured in the fall of 2014 when members learned that the 2015 Imagine competition was going to feature drones instead of cars.

Chmielowiec, who had returned to campus from co-op, asked Carville if she could investigate other races. She found one in Loudon, N.H., run by Dartmouth and supported by the Society of Automotive Engineers.

The race required the team to build a car from the ground up. Team leaders outlined a $100,000 budget—10 times what they had spent on any of the previous races—and they took their plan to Dean Palmer.

Palmer remembers having two concerns: Could they raise the funds needed to be successful, and were the students committed?

Twenty-six percent of this academic year’s incoming engineering class is female, higher than the national average of 19 percent. Palmer said that percentage grows in each class each year because women are retained

at a higher rate than men.

But although the number of women in engineering at RIT has tripled in the last decade, Palmer worried that it could be hard finding enough students to participate.

“You need a lot of people because there are a lot of components,” he said, adding that students have to also juggle their academic workload and co-ops. “The fact that we can put together an all women’s team is a testament to RIT’s demonstrated ability to recruit women.”

Knowing the task was big, the women decided they would need more than a year to fundraise and build the car, so they set their sights on the 2016 competition.

Although they didn’t compete in the spring of 2015, it was a busy time for the group. The team created a sponsorship packet that individual members could send to companies. They also began a crowdfunding campaign through RIT last spring that raised more than $11,200—$1,200 over their goal—primarily from family and friends.

The fundraising part of Hot Wheelz produced self-confidence boosts for many members.

Kristin Zatwarnicki, a fourth-year mechanical engineering student from Long Island on the wheel assembly and brakes team, met with top level officials at Advanced Atomization Technologies in Clyde, N.Y., when she was on co-op last year and asked them to sponsor the team. The company donated $1,000.

“They loved it. They said, ‘could you put a fuel nozzle on the car?’” Zatwarnicki said about the company that makes fuel nozzles for GE commercial airplane engines. “I have so much more confidence because of Hot Wheelz. Talking to large groups or talking to people about Hot Wheelz, it doesn’t really scare me.”

Leading to jobs

The next step was drumming up interest with larger companies. Carville, who is now senior director of College Alumni Relations, approached Sarah Burke, mechanical engineering career services coordinator at RIT, and suggested they arrange a meet and greet before the spring 2015 career fair.

Burke organized a networking event with both Hot Wheelz members and participants in the Society of Women Engineers (SWE).

The event was a success, so Burke, who became a volunteer adviser for Hot Wheelz, expanded it before last fall’s career fair, inviting all six of RIT’s performance teams to a networking open house. This one was even more of a hit with company representatives. Some said they were drawn to the event because of the uniqueness of an all-female team.

“Employers want to see the performance teams,” Burke said. “Why? They have hands-on experience. They know how to turn a wrench. They aren’t theoretical engineers.”

The success of the career fair open house energized Burke, who a few weeks later was attending the national SWE conference in Nashville with 14 students. Her goal at that annual conference was not only to help the SWE students navigate a large career fair, but to tackle the Big Three automakers on behalf of RIT.

As Burke explained, RIT is the biggest supplier of co-op students and full-time hires to Toyota. RIT has a huge presence at Honda and is a key school for BMW and Tesla Motors. And 95 percent of the co-op students at the General Motors facility in Rochester come from RIT.

But when it comes to the Big Three manufacturers in Detroit, it has been difficult getting RIT students in the door.

“I was determined this time to change it because now I had something really unique and different to sell them, and that was a women’s Formula team,” Burke said.

She walked into the General Motors booth and began sharing the Hot Wheelz story with a representative, who immediately got the attention of the lead person from talent acquisition.

“The women’s team is starting to open the door,” Burke said, “but other students will benefit.”

Enhancing the curriculum

In the meantime, team members began to work on the car and looked for ways to tie Hot Wheelz to the curriculum.

Chmielowiec created a proposal for a Hot Wheelz-themed senior design project. Multidisciplinary senior design is a required two-semester class for mechanical, electrical, biomedical and industrial engineering majors. In this class, students can either propose their own project or get assigned to a project.

Chmielowiec not only had to write the proposal but she had to find students who were ahead in the coursework and willing to do senior design off sequence from spring to fall instead of fall to spring. Chmielowiec and Smith and four others not from Hot Wheelz enrolled. The mixed-gender team built a test bench that the team will use to test the electrical system before it is installed on the car.

Team leaders also developed an independent study chassis design class through the mechanical engineering department. Chmielowiec wrote the syllabus, picked a textbook and Marca Lam, senior lecturer in mechanical engineering, stepped in as faculty adviser. Chmielowiec, Smith and teammate Emily Wood, a fourth-year mechanical engineering student, completed the automotive elective last spring.

A second independent study class is being offered again this semester using some of Chmielowiec’s curriculum. She not only tweaked it to make it better for the next set of students, but Chmielowiec is currently mentoring three female students through the semester course.

“It’s a way to pass down what I learned,” Chmielowiec said. “When I leave, I am not leaving a clueless team. I’m leaving an empowered team.”

Outside of class, co-leaders Chmielowiec, the technical team leader, and Smith, the project manager, began forming subgroups—wheel assembly and brakes, circuit design, drivetrain, steering and cockpit design, among others.

Missy Miller, a fourth-year industrial and systems engineering student from Belvidere, N.J., became electrical manager. Miller knew very little about cars when she started. Now she leads a team of 15 students.

Six team members took welding classes at Mahany Welding, which is owned by Michael Krupnicki ’99 (MBA). Krupnicki didn’t charge the team members as a way for him to give back to RIT. And they contacted engineering alumnae to consult on the project.

Last spring, 16 team members and their advisers visited the 2015 competition to learn about all of the different aspects of the race. They also realized that they were unique.

“I don’t think we were there an hour and everybody at the place was talking about the all-girls engineering team that was visiting,” technical adviser Schooping said. “They were the rock stars of the event and they didn’t even have a car there.”

They met representatives from General Motors and impressed them so much that they were assigned a mentor, who began

talking with them through Skype.

That’s also where Chmielowiec first met GM program manager Colón, who was discovered by GM in 1994 at a Formula SAE race when she was the leader of her team from the University of Puerto Rico and one of few women at the race.

The relationships they made there along with Burke’s at the SWE conference resulted in a daylong meeting and tours at GM in Detroit in October. Hot Wheelz members presented to eight executive directors.

“Needless to say,” Burke said, “every one of them wanted to hire the entire team.”

The race

The New Hampshire competition, which is in its 10th year, is supported by the Formula SAE Collegiate Design Series. The event

consists of the same components of the past three Imagine races: acceleration, autocross and endurance. Design and project management presentation are also evaluated.

This time, though, getting to compete May 1-5 will be more of a challenge.

The team is required to submit about a dozen technical reports with updates on the hundreds of pieces that go into the car before even leaving for the competition.

Then when they get to New Hampshire, they’ll have to pass inspection. If they don’t, the car won’t get on the track.

Caitlin Babul, a fourth-year mechanical engineering honors student from Chicago, was appointed safety and rules manager. It’s Babul’s job to make sure the team complies with 178 pages of rules.

Babul said she joined Hot Wheelz as a freshman because she knew she would get a hands-on role and she liked being a part of an all-female team in a male-dominated industry.

Her past work with the team helped her land a two-term co-op with Toyota as a production engineer. She was one of only four women in her office of about 50.

She is happy to have the leadership position this year.

“When I came here I didn’t know what I wanted to do with a mechanical engineering degree,” she said. “Then I joined Hot Wheelz, and I was like, ‘cars are kind of fun.’ Then I went to Toyota, and I was like, ‘cars are really cool.’”

Becky Michalski, a third-year mechanical engineering student from Buffalo, N.Y., on the drivetrain group, said working closely with electrical engineers on Hot Wheelz helped her on her co-op at Canon last fall.

“I am not electrically minded at all, so being able to have done that at school before I was in the real world was a nice learning experience,” said Michalski, who would like to go into automotive or toy design after she graduates.

Smith and Chmielowiec have been working hard to set up a succession plan for students such as Michalski and second-year mechanical engineering major Zoe Bottcher, who is the steering team leader and is enrolled in the independent study

class created by the team.

This summer, Bottcher will do her first co-op at Magna Exteriors, part of Magna International, which has established a co-op position specifically for a Hot Wheelz member on a year-round basis.

The fundraising plan calls for carrying over $20,000 of the $100,000 they hope to raise so next school year members aren’t starting from scratch. They already have $78,000, with 14 companies, the Kate Gleason College of Engineering and Destler kicking in funds.

Before she leaves, Smith, who will begin work in July for Keurig Green Mountain in Burlington, Mass., is making sure they are documenting all of their work so the team has procedures to follow.

Carville, Schooping and Burke will be there to guide and grow future teams and expand their relationships with alumni and companies.

This kind of networking was Carville’s dream when she first approached the dean about forming a team.

Chmielowiec is also fulfilling her dream. She will begin a position this summer at GM in Detroit as a tire, wheel and fastener performance and test engineer. Colón will be her mentor.

“At the end of the day we want to bring the best of the best to work at GM,” Colón said. “Maura is an example of that.”

It’s the first step, Chmielowiec said, to working in NASCAR.

Dean Palmer expects to see many other successes from team members—at the May competition and beyond.

“I see them achieving much more than they would ever anticipate,” Palmer said. “It’s because they have that sheer will to succeed, plus, of course, a great RIT education.”

Hot Wheelz co-leader Jennifer Smith, a fifth-year mechanical engineering student, uses a vertical milling machine to drill and tap holes into parts for the car. Smith said Hot Wheelz gave her a unique set of skills that helped her get a full-time job after graduation. A. Sue Weisler

Hot Wheelz co-leader Jennifer Smith, a fifth-year mechanical engineering student, uses a vertical milling machine to drill and tap holes into parts for the car. Smith said Hot Wheelz gave her a unique set of skills that helped her get a full-time job after graduation. A. Sue Weisler Jan Maneti, operations manager for the Department of Mechanical Engineering, instructs team members in the machine shop. From left to right are undergraduate students Maura Keyes, Missy Miller, Elise King, Kayleen Welch, Annika Garbers and Amiee Jackson. A. Sue Weisler

Jan Maneti, operations manager for the Department of Mechanical Engineering, instructs team members in the machine shop. From left to right are undergraduate students Maura Keyes, Missy Miller, Elise King, Kayleen Welch, Annika Garbers and Amiee Jackson. A. Sue Weisler Zoe Bottcher, a second-year mechanical engineering major, welds the car’s frame at Mahany Welding. Six team members took welding classes at Mahany, which is owned by Michael Krupnicki ’99 (MBA). A. Sue Weisler

Zoe Bottcher, a second-year mechanical engineering major, welds the car’s frame at Mahany Welding. Six team members took welding classes at Mahany, which is owned by Michael Krupnicki ’99 (MBA). A. Sue Weisler Missy Miller, a fourth-year industrial and systems engineering student, works with Maura Chmielowiec on the frame at Mahany Welding. Alumnus Michael Krupnicki allowed Hot Wheelz team members to use the space as a way to give back to RIT. A. Sue Weisler

Missy Miller, a fourth-year industrial and systems engineering student, works with Maura Chmielowiec on the frame at Mahany Welding. Alumnus Michael Krupnicki allowed Hot Wheelz team members to use the space as a way to give back to RIT. A. Sue Weisler Hot Wheelz members Missy Miller, front left, and Cassie Kaczmarek, back right, consult with team leaders Jennifer Smith, front right, and Maura Chmielowiec in the Hot Wheelz team room in the Kate Gleason College of Engineering. Caitlin Babul, the team’s safety and rules manager, works on the computer behind them. Maxwell Harvey-Sampson

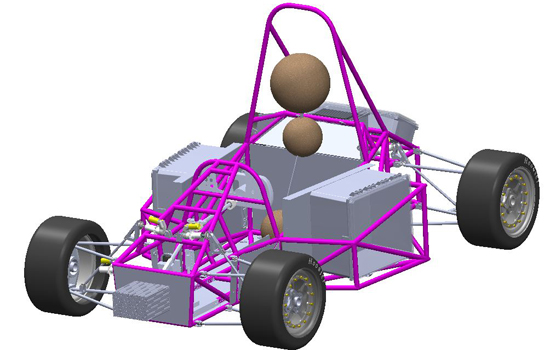

Hot Wheelz members Missy Miller, front left, and Cassie Kaczmarek, back right, consult with team leaders Jennifer Smith, front right, and Maura Chmielowiec in the Hot Wheelz team room in the Kate Gleason College of Engineering. Caitlin Babul, the team’s safety and rules manager, works on the computer behind them. Maxwell Harvey-Sampson Hot Wheelz members hope to finish the car by the end of March so they can test drive it in April.

Hot Wheelz members hope to finish the car by the end of March so they can test drive it in April.