NTID celebrates 50 years

RIT Archive Collections

Lady Bird Johnson attended the dedication of the NTID complex in October 1974. During the ceremony, the first lady spoke with U.S. Rep. Hugh Carey, center, and shook hands with Bill Ingraham, one of NTID's first graduates.

Fifty years ago, 19-year-old Bill Ingraham was about to enter uncharted territory.

After graduating from Brockport High School in upstate New York as its only deaf student, Ingraham had earned a hard-won associate degree in applied science/ business administration from Alfred State.

“I knew that I wanted to earn my bachelor’s degree, but I also realized that in order to do that, I needed a lot of help,” said Ingraham, who had struggled academically at Alfred, relying heavily on his lip-reading skills and a roommate who shared class notes.

Ingraham’s cousin told him that a new “program” was starting in the fall of 1968 at Rochester Institute of Technology and that he should consider applying for admission.

Ingraham became one of 70 deaf pioneers of RIT’s National Technical Institute for the Deaf, the first-ever college uniquely designed to teach deaf and hard-of-hearing students the technical skills necessary for them to get quality jobs. NTID’s first director, D. Robert Frisina, called it the “Grand Experiment” to describe educating deaf students in a college setting with their hearing peers.

“The thing about NTID was that there was no model to follow,” Frisina has said. “This was a rare opportunity in the education of deaf people.”

Throughout the next 50 years, NTID would become a catalyst for diversity and inclusion on campus, creating a post–secondary learning environment never before seen in this country. With the emergence of more than 200 majors, research opportunities, doctoral degree readiness programming and a 94 percent career placement rate, the “Grand Experiment” is a grand success.

History in the making

The story of RIT’s NTID began when the first permanent public school for deaf students in Hartford, Conn., opened in 1817. The school showed that deaf people could be academically successful.

According to Harry Lang, professor emeritus and co-author of From Dream to Reality: The National Technical Institute for the Deaf, A College of Rochester Institute of Technology, while many residential schools continued to appear throughout the country, including Rochester’s own school for deaf students in 1876, a dedicated postsecondary school that focused on marketable technical skills remained a dream.

In 1964, Congress was urged to study the educational and employment status of deaf people. One report suggested that about 80 percent of deaf adults were working in manual occupations, whereas only about 50 percent of the hearing population assumed those same types of positions.

Shortly after, the House and Senate drafted bills recommending the establishment of a college tailored to the needs of deaf and hard-of-hearing students pursuing technical careers. The legislation was passed in both the House and the Senate in a record-setting 47 days.

On June 8, 1965, President Lyndon Baines Johnson signed Public Law 89-36, establishing the National Technical Institute for the Deaf.

With the bill signed and plans for its execution moving quickly, more than two dozen universities across the country applied to establish the college on their campuses.

However, with connections to industry and business, pre-established programs in many technical disciplines, a favorable relationship between Rochester industry and people with disabilities, and a steady stream of deaf students who had already enrolled in some existing RIT programs, particularly in the School of Printing and the School for American Craftsmen, RIT became a strong contender.

In July 1966, a site team visited RIT’s new 1,300-acre campus under construction in Henrietta. On Nov. 14 of that year, RIT was selected as the future home of NTID.

The strengths of this initiative would be a new, blended learning environment for the nation’s deaf students interested in technical careers and an enhanced learning environment for the university’s hearing population.

‘I was the first’

Ingraham visited campus the summer before NTID opened. He used lip reading to conduct an interview and then went on a tour.

“They accepted me immediately,” Ingraham said. “I was the first.”

Ingraham knew that the eyes of the country—including the legislators and advocates who invested so much in this endeavor— would be trained on him, his classmates and Frisina, who was named director in 1967.

Before NTID’s charter class arrived on campus, less than 1 percent of college-aged deaf people had enrolled in higher education.

Ingraham remembers being excited for the opportunity to take his education further but was apprehensive at the same time. “I think we all felt that way.”

But after he met other students, including his deaf roommates from Pennsylvania and Florida, he felt more comfortable.

Many deaf students were drawn to science, technology, engineering and math, based partly on the visual nature of the subject material, and RIT was well positioned to offer these programs to its deaf learners.

Students could enroll in programs such as electrical and mechanical engineering, business administration, printing management and medical technology, and degrees ranging from two-year associate, to Master of Science and Master of Fine Arts degrees. Ingraham studied business administration.

“Many people don’t really realize how significant NTID was for opening doors and opening minds of the students who wanted to pursue STEM careers, and faculty, like myself, who taught in those disciplines,” said Lang, who taught at NTID for 41 years.

But there were growing pains during those inaugural years. During the first year, RIT didn’t have full-time interpreters on staff, and only a few of the newly hired staff knew sign language.

The deaf students and the other 10,000 hearing RIT students were hesitant to mingle with one another due to perceived communication barriers and a lack of understanding of deaf culture. Despite the university’s efforts to reach out to deaf students, some, who were living on their own for the first time, dropped out due to social and academic challenges.

“There was a definite sense of separation in the past,” explained Gerry Buckley, NTID president and RIT vice president and dean, and a 1978 alumnus of RIT’s social work program. “Lyndon Baines Johnson Hall, NTID’s academic building (which opened in 1974 but wasn’t named until 1979), was far away from what was perceived as the ‘main’ campus. Some hearing students would refer to us as ‘NIDS,’ National Institute of Deaf Students.”

But as the years progressed and the technology behind deaf education developed, the climate and attitudes changed.

In the late ’60s and early ’70s, access to telephone services included experimental devices such as Codecom, which required knowledge of Morse code, and the “Vista Phone,” a video-telephone communication system that could only be used on campus. The Victor Electrowriters allowed deaf and hearing people to communicate by telephone through an electric stylus system.

By the 1970s, the teletypewriter (TTY) made telephone communication much more accessible.

In 1968, captioning technology was not yet developed sufficiently. On-campus educational media was often interpreted for deaf students.

“I still have a video of myself teaching temperature and pressure in physics class with index cards and a video recorder,” Lang said. “That was my captioning during the early years.”

But by the late 1970s, NTID had become a national leader in educational program captioning, which helped deaf students become fully engaged with access to televised news, student information, announcements, academic course information and entertainment programming.

Today, with automatic speech recognition, captioning and C-Print, a real-time speech-to-text system developed at the college, NTID remains a progressive leader in instructional and communicative technologies.

RIT has the largest staff of professional sign language interpreters of any college program in the world. Last year, RIT provided more than 140,000 hours of interpreting services, which includes classroom interpreting as well as interpreting for non-academic pursuits such as athletic events, religious services, concerts, presentations and other student life activities.

Trained student notetakers record information during classes or laboratory lectures, discussions or multimedia presentations. Last year, RIT provided more than 60,000 hours of notetaking services for students. Real-time captioning provides a compre–hensive English text display of classroom lectures and discussions.

“Coming to NTID is a real homecoming for many deaf and hard-of-hearing students,” Buckley said. “This is one of those places where you have the right to understand and be understood 100 percent of the time. Some students come here and aren’t even aware of how much they have been missing. Here, our students can fully participate in a college experience, both socially and academically.”

Opportunities today

Grace Yukawa is an example of that. The fourth-year mechanical engineering student is an NTID student ambassador, member of a sorority and works for the College Activities Board.

In high school in Seattle, Yukawa was one of about 40 deaf students in a fully mainstreamed environment with 1,700 hearing classmates. She generally interacted with her close-knit group of deaf and hard-of-hearing peers. However, at NTID, she loves the enthusiasm of her hearing peers who are interested in learning more about deaf culture.

“NTID has helped me find myself,” Yukawa said. “Back home, I see the same people every day in our very small deaf community. Here at NTID, I meet so many new people, people with many different backgrounds—deaf people, hearing people, people who are late deafened, deaf people who sign, hearing people who sign, deaf people who are oral. I just knew that I wouldn’t be alone here, and that was just so important when I was selecting a college.”

The reputation of RIT’s mechanical engineering program also played a role in Yukawa’s decision to enroll.

“My major requires four co-ops, and if it wasn’t for the networking in the deaf community and using the resources that NTID has to offer, I don’t think I would have secured those on my own,” she said. “Many of the companies that I applied to were hoping to hire deaf people or people with other disabilities to broaden their scope. I wasn’t aware that those specific opportunities even existed.”

Out in the field, Yukawa has done research on 3D bioprinting and on children and adults living with disabilities. Her observation visits to preschools and rehabilitation centers have provided her with insights into cerebral palsy, autism spectrum disorders and people who use wheelchairs. She hopes to continue work on devices that can be designed to make it easier for these individuals to complete daily tasks.

NTID actively sponsors and encourages research designed to enhance the lives of deaf and hard-of-hearing people. It is home to research centers that are dedicated to studying teaching and learning; communication; technology, access and support services; and employment and adaptability to social changes and the global workplace.

Opportunities are available for under–graduate and graduate students to work directly with faculty, travel in support of their research and apply for research funding.

The Rochester Bridges to the Doctorate program, a partnership between RIT and University of Rochester, is the first of its kind that provides scientific mentoring for deaf and hard-of-hearing students to become candidates for doctoral degree programs in biomedical or behavioral science disciplines.

And Sebastian and Lenore Rosica Hall, the $8 million, state-of-the-art building that binds this all together, fosters innovation, entrepreneurship and research among deaf, hard-of-hearing and hearing peers.

Yukawa has one more year until graduation but is looking ahead to a career designing accessibility devices.

She will join more than 8,500 deaf and hard-of-hearing NTID alumni living in all 50 states and in 20 countries, and working in all economic sectors, including business and industry, health care, education and government.

“My hope is to one day be able to level the playing field for people living with disabilities,” she said.

Fifty years later

NTID has already helped level the playing field for many of its graduates.

“There is an evolution that we have witnessed over the past 50 years,” said John Macko, director of NTID’s Center on Employment.

Fifty years ago, the Americans with Disabilities Act didn’t exist, and it was a new concept for employers to consider deaf and hard-of-hearing graduates as employees. It was more challenging for deaf and hard-of-hearing graduates to work alongside hearing coworkers.

“Years ago, deaf and hard-of-hearing people were office clerks, data entry specialists and computer operators,” Macko said. “Today, we’re accountants, network specialists, mechanical engineers, software engineers. Job titles have changed as a result of NTID.”

As a student, Ingraham excelled at tax accounting. His instructor, Bill Gasser, encouraged him to apply for a co-op with the Internal Revenue Service.

“He believed that I could do the job and had every confidence in my abilities. He always looked out for me in class; I’ll never forget him and what he did for me.”

After graduating in 1971, Ingraham was hired by the IRS and served as a revenue agent until his retirement 36 years later.

“I’m just amazed at what NTID has become,” Ingraham said. “I’m so happy that I had the chance to go there and I’m so happy for the students who have the opportunity to go there now. NTID introduced me to how amazing the deaf world really is.”

He and his wife, Mary Jo (Nixon) Ingraham, remain connected to NTID, serving on committees and regularly attending campus events. Mary Jo graduated in 1972 and became the first NTID alumna hired on staff.

Buckley, who was named NTID president in 2011 and is the first RIT/NTID alumnus to hold that position, said students today leave prepared for the real world, where there isn’t always sensitivity and inclusion. They leave understanding their rights and responsibilities, and they leave with the self-confidence to interact with hearing peers.

“As RIT and NTID prepare the next generation of leaders, I want them to walk away from this campus feeling that they were included. I want them to increase their earning potential and economic power,” Buckley said. “But it’s not just about money. It’s about the ways they can influence the world. In that way, we’ve truly fulfilled our mission.”

50th reunion weekend

In celebration of NTID’s 50th anniversary, a reunion weekend June 28–July 1 will feature events and activities for alumni and families. Events include an opening ceremony, NTID Alumni Asso–ciation golf tournament, several theatrical productions, a “welcome home” celebration, NTID Alumni Museum preview, campus tours, reunion group photos, children’s activities and more.

The reunion committee is also asking NTID community members to participate in the #NTID5for50 fundraising campaign, encouraging individuals to make gifts in dollar amounts beginning with a five.

More history

A Shining Beacon: 50 Years of NTID will be available during the reunion weekend. The book includes chapters written by individuals who have witnessed change throughout the years at NTID, as well as by recent graduates looking forward to the next 50 years.

The book also includes chapters on the introduction of American Sign Language on campus, the history of performing arts at NTID, the growth of STEM education, athletics and job placement.

Performing arts

NTID performing arts launched in 1974 after the success of a student drama club founded by Robert Panara, NTID’s first deaf faculty member and co-founder of the National Theater of the Deaf.

Today, performance groups host several productions each season, and a comprehensive curriculum of dance and theater courses is offered. Thomas Warfield, NTID’s director of dance, explained that many deaf and hard-of-hearing students are excited for the chance to perform and said that performing arts classes are often filled to capacity. “We take a different point of view of theater and approach it from multiple angles, engaging a diverse spectrum of students,” he said. “NTID performing arts is an opportunity to make our unique impact on theater and dance.”

Bill Ingraham is one of NTID's first graduates. A. Sue Weisler

Bill Ingraham is one of NTID's first graduates. A. Sue Weisler NTID has helped level the playing field for its graduates, which include members of the charter class pictured here. RIT Archive Collections

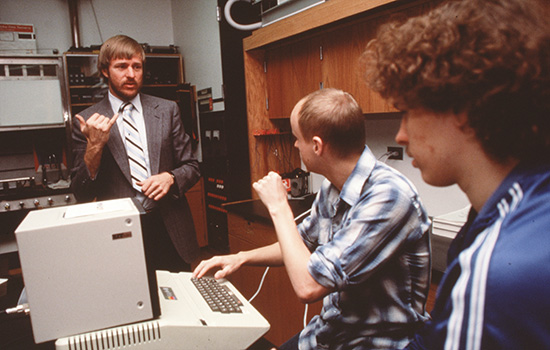

NTID has helped level the playing field for its graduates, which include members of the charter class pictured here. RIT Archive Collections Harry Lang, left, taught at NTID for 41 years. He said RIT was well positioned to offer deaf and hard-of-hearing students classes in science, technology, engineering and math. RIT Archive Collections

Harry Lang, left, taught at NTID for 41 years. He said RIT was well positioned to offer deaf and hard-of-hearing students classes in science, technology, engineering and math. RIT Archive Collections Gerry Buckley, NTID president and RIT vice president and dean, right, talks with former student Robb Dooling, who graduated in 2014. Mark Benjamin

Gerry Buckley, NTID president and RIT vice president and dean, right, talks with former student Robb Dooling, who graduated in 2014. Mark Benjamin Fourth-year student Grace Yukawa says NTID has helped prepare her for a career in mechanical engineering. Yukawa believes that RIT's community of deaf, hard-of-hearing and hearing people makes the university unique. A. Sue Weisler

Fourth-year student Grace Yukawa says NTID has helped prepare her for a career in mechanical engineering. Yukawa believes that RIT's community of deaf, hard-of-hearing and hearing people makes the university unique. A. Sue Weisler