NTID 50th Anniversary – History

NTID 50th Anniversary

History

Milestones in NTID History

By James McCarthy

In 50 years, RIT/NTID has seen its fair share of change. Having gone from a group of 70 deaf and hard-of-hearing students who didn’t have a building to call their own to more than 1,200 students spread across a functional and attractive complex of buildings, backed by a worldwide population of more than 8,000 alumni, “transformation” could be considered an understatement for NTID. Here, we review only a few of the high points in the past 50 years, paying attention to common themes of leadership and growth in pursuit of NTID’s mission of ensuring employment for deaf and hard-of-hearing students. Running through Dr. Frisina’s appointment as NTID’s first dean to Greg Pollock’s second election as president of RIT’s Student Government, overseeing the campus activities of more than 16,000 students, we can almost glimpse the road that RIT/NTID has been—and still is—traveling, as an institution and a community. One important note: You’ll see that the construction of the various buildings of NTID has been omitted from this timeline. That’s because this is a story about people. If you’d like to know more about the buildings of NTID, check out “The changing campus landscape.”

1967

Dr. D. Robert Frisina begins his first year leading NTID.

1968

NTID’s first class of admitted students—known as the “Charter Class”—begin classes.

1971

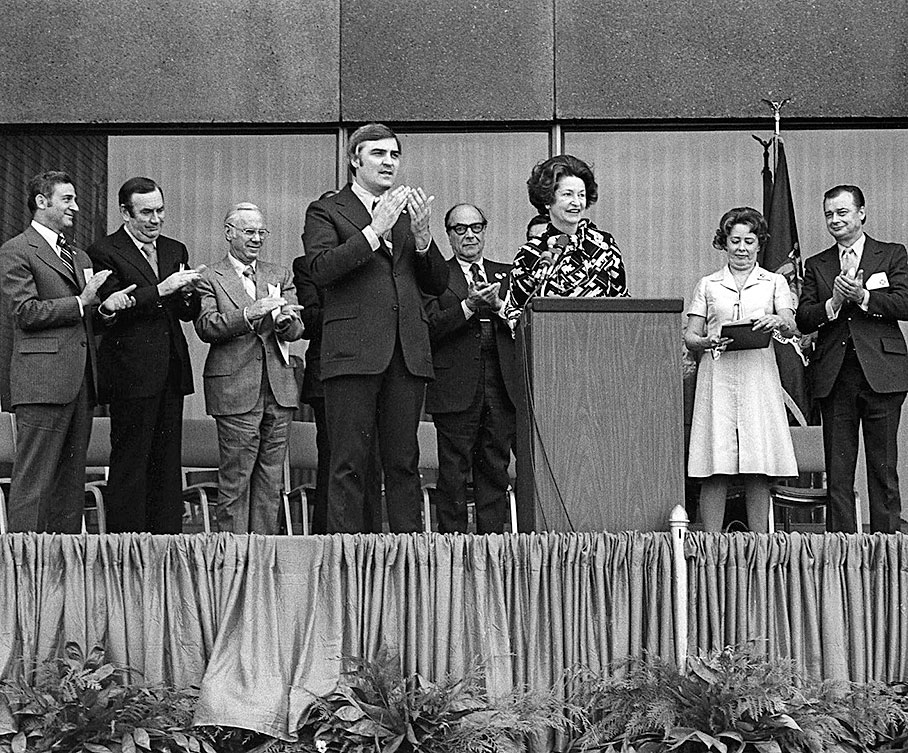

The groundbreaking ceremony for the NTID complex is held.

1972

The first NSC Board of Directors is elected; clockwise from bottom left: Mark Feder (SVP ‘71, ‘74, ‘76), vice president; Miriam Sotomayor (‘72), secretary; Jerry Nelson, president; and John Swan (SVP ‘70, ‘74, ‘76), treasurer.

1978

The NTID Center on Employment is established, solidifying NTID’s commitment to job placement for deaf and hard-of-hearing students.

1978

John “JT” Reid graduates as the first deaf captain of an RIT varsity team (wrestling).

1988

The theater in LBJ Hall is named “Robert F. Panara Theatre” after Dr. Panara, pictured with his wife, Shirley.

1995

James DeCaro, who served as NTID dean 1985-1998, is named dean and interim director of NTID. He was named interim president of NTID in 2010.

1996

Dr. Robert Davila is appointed NTID’s first deaf—and Latino—vice president.

2003

Dr. T. Alan Hurwitz is appointed vice president and dean of NTID. In 2008, he was named NTID’s first president.

2006

Elizabeth Sorkin (SVP ‘99, ‘07) is elected the first deaf president of RIT’s Student Government.

2010

Greg Pollock (‘12) is the second deaf president of RIT Student Government—and the first to win a second term.

2011

Dr. Gerard J. Buckley (‘78) becomes the first alumnus to be appointed leader of NTID.

"A Shining Beacon"

Excerpts From a New NTID History Book

By James McCarthy

In time for NTID’s 50th Anniversary Reunion Weekend, NTID is releasing a new history book. Titled “A Shining Beacon: Fifty Years of the National Technical Institute for the Deaf,” the book collects chapters written by more than 30 authors about NTID’s multifaceted history. The following excerpts are examples of the many stories that intertwine throughout this book.

![]()

LBJ at Twilight: The cover of "A Shining Beacon"

Dr. Bonnie Meath-Lang, Dr. Aaron Kelstone, Jim Orr

NTID’s commitment to the performing arts began even before the arrival of Deaf students on the RIT campus.

The founding director of NTID, Dr. D. Robert Frisina, in his request for funding of the Lyndon Baines Johnson academic building, specified that a full, state-of-the-art theater be constructed as part of it, cautioning that it not be an auditorium, or a “cafeteria with a platform.” He envisioned the theater as a welcoming place where Deaf and hearing students and faculty could come together on the RIT campus. Frisina also saw theater as a way for students to develop self-confidence, learn literature and history and showcase their art to the wider community.

He was very much influenced by his colleague and friend, Gallaudet College English and drama Professor Robert F. Panara. In addition to his teaching and writing, Panara had served on the National Advisory Board that selected RIT as the resident campus for NTID and developed the guidelines for its mission. Panara was a charismatic teacher, whose creative signing in literature classes and in performance was cited by William Stokoe as an inspiration for his early research on ASL as a language. Frisina was determined to bring Panara in as NTID’s first Deaf faculty member, citing his ability to teach and advise both Deaf and hearing students. Panara enjoyed his work at his alma mater, Gallaudet, but he was ready for a change and a new adventure. Frisina recalled his own strategy in piquing and persuading his friend: “In wooing Bob to NTID, I indicated that he would be the ‘Laurent Clerc’ of this new college.”

Panara came to RIT in 1967, in advance of the first NTID class. He taught language and literature classes in the then-RIT College of General Studies (now Liberal Arts), and met with hearing students regularly to discuss the profound cultural change that would come to RIT with the presence of NTID. He also worked with Frisina on the proposals for the new academic building and its theater. In 1968, with the arrival of the first students, Panara headed the English program, and began a series of sign language and drama workshops. In the 1969–70 academic year, with the popularity of the workshops and a visit from the famed Deaf actor Bernard Bragg in the fall, momentum built for the establishment of a drama club.

That winter, on a snowy night where students had to trek a quarter mile to the Webb Auditorium to vote, the Masquers Drama Club was established.

A dramatic scene: Patrick Graybill, as Prospero, chastises Caliban in the 1981 production of "The Tempest."

Miriam Lerner

If this chapter were a river, we would now have side channels to wander, as there are two concurrent stories that meet again further downstream.

One story also takes place in the early 1980s, when a small group of extremely creative Deaf students at NTID began having parties in their rooms and playing translation games. They would read a story or a comic book, look at illustrated magazine or album covers (this was before CDs, iPods, or personal computers), and attempt to “translate” and perform the images in ASL. They played with the language and stretched their imaginations in ways they had not attempted before, but the aggregate synergy of their inner visions pushed them in surprising ways. Other students heard about the fun, and the rooms were soon so crowded that another venue had to be found to accommodate their fans and to carry on their experimentation.

At the time, there was a bar called The Cellar located in the tunnels underneath the dorms at NTID. The sign-play parties migrated there, and soon students were taking turns performing on a makeshift stage for any and all who showed up. One of those students was Peter Cook, who would later go on to become an accomplished ASL poet and storyteller, as well as a respected interpreter trainer, ASL and Deaf Studies professor, and chair of the ASL department at Columbia College Chicago.

It was Cook who came up with the idea of naming these weekly performances at the Cellar “The Birdsbrain Society,” after seeing a poem by Allen Ginsberg of the same name. Cook was also the person responsible for organizing these first poetry “readings” in ASL by Deaf students. It was during this time that [Jim] Cohn first interviewed Cook about ASL poetry and began publishing his poetry in “ACTION,” a magazine of poetry and poets based in the Rochester community.

Meanwhile, in our second story, Cohn was hot on the trail of what ASL poetry might look like…

Dr. Linda Siple and Dr. T. Alan Hurwitz

A history of interpreter education at NTID would be incomplete without further discussion of Alice Beardsley. Beardsley was affectionately referred to as NTID’s First Interpreter. Born hearing, Beardsley became profoundly deaf due to contracting measles and scarlet fever one month after her fifth birthday. She was enrolled at the Rochester School for the Deaf (RSD), where she learned the Rochester Method, which largely consisted of fingerspelling words, rather than using signs. Later, she developed her ASL skills though her involvement in the Deaf community. Many years later, in adulthood, her hearing was surgically restored in one ear, which allowed her to interpret for many deaf and hard-of-hearing people in the Rochester community. In 1965, Beardsley served as the interpreter for the site-visit team that selected RIT as the host institution for NTID.

Bracing for impact: Alice Beardsley leads morning exercises for interpreting students in the Quad on July 11, 1979, the day Skylab fell to Earth—hence the targets on the students' heads.

Once established, NTID hired Beardsley, where she served as a staff interpreter for more than 10 years. A series of severe ear infections once again left Beardsley profoundly deaf; unable to interpret in the classroom, she moved to the Department of Support Services Education and started training interpreters. Those fortunate to have Beardsley as an instructor will remember her impish grin and lightning-fast fingerspelling developed when she learned the Rochester Method at RSD. Most memorable were “morning exercises” during the [Basic Interpreter Training Program] BITP, which Beardsley taught every day in the NTID quad at 8:00 a.m., accompanied by Barry Manilow songs. She loved a good prank and could take it as well as she gave it. One morning in the summer of 1977, Beardsley arrived to find a pile of papers and no students. The papers contained a variety of excuses explaining the students’ absences (e.g., “Dear Alice Beardsley, Please excuse Pat from exercise class. She has a hang nail. Signed, Pat’s mother.”)

Tabitha Jacques and Robert Baker

Deaf artists have existed for centuries, but there have been limited resources for documenting and preserving the history of deaf-related art. That began to change when Gallaudet University was founded; after forming their Archives unit, efforts were set in motion to collect art by deaf artists and document information about their biographies, techniques, and processes.

As more attention began to be paid to deaf-related art, other organizations that began to contribute to this collection and the preservation efforts included residential schools for the deaf, the National Association of the Deaf (NAD), and the Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf (AGBAD).

In cases where deaf-related art was not actively collected or documented, environments where the general networking of artists could take place continued to grow. In the late 1980s, the Deaf Way I Conference sparked the movement of Deaf View/Image Art (De’VIA), where a group of artists came together and drafted a manifesto that shaped their art. This was probably the first group of deaf and hard-of-hearing artists that started a movement. Although the Deaf Art Movement of the 1970s emerged earlier, it was powered mainly by a single artist named Ann Silver (and possibly a few other artists), but the movement did not become as widely recognized as De’VIA is.

At the same time that deaf-related art and the movements surrounding it were beginning to coalesce into what could be termed a “school” or a “philosophy”, NTID was founded in 1968. Applied Arts was one of the first academic programs. Many of the De’VIA founding artists were NTID alumni and graduates from the program, such as Guy Wonder (’71) (one of the first students to enroll at NTID), Chuck Baird, and Paul Johnston. Nancy Rourke, also a graduate of NTID, spearheaded the second wave of De’VIA in 2009. Many other previous graduates also identify with the second wave of De’VIA and participate heavily in the De’VIA Central Facebook page that has over 4,000 members.

In 1976, upon the completion of NTID’s Lyndon Baines Johnson (LBJ) Hall, C. Tim Fergerson, a professor in the Applied Arts, founded the NTID Art Gallery in the reception space for the office of the Director of NTID. Very little information is recorded, but it is assumed that 1976 was the same year that NTID started to collect art by deaf or hard-of-hearing people, at first drawing from the work of NTID students and art faculty. In this way, NTID became the second institution to actively collect and preserve deaf-related art. In 1984, the NTID Art Gallery expanded, and it was designated as the Mary E. Switzer Gallery.

In 2000, NTID received over $2.5 million from the Dyer family, and a matching federal grant to focus on collecting, preserving, and displaying art by deaf and hard-of-hearing people. A beautiful 7,000-square-foot gallery was built and named the Joseph C. and Helen F. Dyer Arts Center. To date, the Dyer Arts Center houses approximately 1,000 pieces of artwork, and the collection is growing every year.

Dr. Ernest Hairston Appeared from the Popcorn Can (2015): A collage by Takiyah Harris (’99), De'VIA artist.

Foreword: Dr. Gerard J. Buckley

Introduction: “RIT/NTID Alumni Make Their Mark”: Loriann Macko

The People

“Signs of Change: ASL on Campus”: Jeanne Behm and Dr. Kim B. Kurz

“Finding a Home on Stage: The History of Performing Arts at NTID”: Dr. Bonnie Meath-Lang, Dr. Aaron Kelstone, and Jim Orr

“The Kitchen Light of NTID”: Miriam Lerner

“Empowerment: The Importance of Deaf Cultural Studies”: Patti Durr

“Dyer Arts Center: A New Home for Deaf Artists”: Tabitha Jacques and Robert Baker

“Developing Leaders: The NTID Student Congress and Student Organizations”: Greg Pollock, Yvette Chirenje, and Roxann Richards

“On the Field of Play: NTID Athletics”: Sean “Skip” Flanagan

The Place

“Leading the Way”: Dr. Gerard Walter

“A Commitment to Equality: Diversity at NTID”: Dr. Charlotte LV Thoms and Dr. Ila Parasnis

“Buildings of the National Technical Institute for the Deaf”: Erwin Smith

“The Changing Face of the NTID Research Enterprise: 1968-2017”: Dr. Ronald R. Kelly

“The Evolution of Access Services”: Stephen Nelson

“On Giants’ Shoulders: A Tradition of Excellence in Teaching”: Dr. Todd Pagano

The Purpose

“From Roots to STEM: The Growth of STEM Education at NTID”: Dr. Todd Pagano and David Templeton

“How to Educate an Interpreter: 50 Years of Interpreter Education”: Dr. Linda Siple and Dr. T. Alan Hurwitz

“Preparing the Next Generations: Training Teachers at NTID”: Dr. Gerald C. Bateman, Dr. Christopher A.N. Kurz, and Dr. Harry G. Lang

“Big Ideas Everywhere: Innovation as Education”: Dr. W. Scot Atkins

“From Classrooms to the Workforce: Job Placement and Success”: Mary Ellen Tait

Conclusion: “NTID 2043: A Living, Evolving and Thriving Institute”: Dr. Peter C. Hauser and Dr. Jess Cuculick

The Changing Campus Landscape

By Ilene J. Avallone

Rochester Institute of Technology’s landscape has changed dramatically in the time since the university moved from downtown Rochester to the Henrietta campus. In that time, NTID’s campus footprint also has changed. New buildings have been constructed, structures have been renovated and new spaces created to reflect the changing ways deaf and hard-of-hearing students live and learn at a world-class university. In this article, “FOCUS” looks at the major construction projects that have created today’s campus landscape for NTID.

NTID Complex

After the National Advisory Board officially announced RIT as the location for NTID on November 14, 1966, the architectural firm of Hugh Stubbins and Associates was hired to design the new complex. The groundbreaking was held in 1971. Construction took three years to complete, and the dedication of the $27.5 million NTID facilities took place on October 5, 1974. The original complex for NTID included the Lyndon Baines Johnson Hall academic building; Mark Ellingson Hall, Peter Peterson Hall and Residence Hall D student housing; and the Shumway Dining Commons.

Hugh L. Carey Hall

Dedicated on October 14, 1984, the building was named in honor of Hugh L. Carey, the former governor of New York state who proposed the bill for NTID in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1965. NTID’s Department of Access Services calls Carey Hall home. In 1991, an addition was built to accommodate the expanding number of interpreters and captionists needed to serve the growing number of deaf and hard-of-hearing students pursuing degrees in the other colleges of RIT.

Joseph F. and Helen C. Dyer Arts Center

Eight months of construction in 2001 turned NTID’s center courtyard into the 7,000 sq. ft. glass-enclosed Joseph F. and Helen C. Dyer Arts Center, the world’s largest gallery devoted to exhibiting significant works by deaf and hard-of-hearing artists. Joseph and Helen Dyer were long-time supporters of NTID. They provided $2.5 million to fund the construction and on-going support of the Dyer Arts Center. The grand opening took place on October 26, 2001.

The Communication Service for the Deaf Student Development Center

Opened in fall 2006, the $6 million 30,000 sq. ft. building is the social and cultural center of campus life for deaf and hard-of-hearing students. The CSD Student Development Center is home to the offices of NTID Student Congress, NTID Student Life Team and multicultural clubs. It also houses a coffee shop, a large multipurpose meeting/conference center and additional meeting rooms, a study center and informal spaces that facilitate interaction and socializing. This includes Ellie’s Place, a lounge area in the center of the SDC that was dedicated in 2012 to honor the late Dr. Eleanor Rosenfield, who was former NTID associate dean for Student and Academic Services. For more than 30 years, Rosenfield was an integral part of the NTID community who worked with students to help realize their fullest potential.

Frisina Quad/Jan Strine Memorial Labyrinth

Frisina Quad is surrounded by Lyndon Baines Johnson Hall, Ellingson and Peterson Halls, and the CSD Student Development Center. It was dedicated in 2007 in honor of Dr. D. Robert Frisina, the founding director of NTID. Frisina Quad is a venue for many events throughout the year, including the annual Apple Festival, held every fall to welcome RIT/NTID students back to school. It is also now home to the Jan Strine Memorial Labyrinth, which was dedicated in 2015. Strine was a mentor to many deaf students over the course of her 30-year career at NTID.

Sebastian and Lenore Rosica Hall

Devoted to innovation and research for students, faculty and staff of NTID, Rosica Hall officially opened on Oct. 11, 2013, and was made possible through a $1.75 million grant by the Chicago-based William G. McGowan Charitable Fund. Additional outside private funds were raised to complete Rosica Hall. The Rosicas were life-long advocates for deaf and hard-of-hearing people. Lenore Rosica was the sister of William G. McGowan, CEO of MCI Communications Corporation, and worked as a speech pathologist. Her husband, Sebastian, worked as an audiologist for 40 years at St. Mary’s School for the Deaf in Buffalo, New York, and was a trustee of the McGowan Charitable Fund.

1968

2017

RIT campus construction by the decade

Take a stroll around RIT these days and it is hard to miss the construction activity or the new structures that have been added over the past 50 years. There have been 132 new buildings and major additions constructed at RIT since the opening of the Henrietta campus in 1968 after relocating from downtown Rochester.

Number of new free-standing buildings and major additions constructed by the decade:

| 1966-1969 | 29 |

| 1970-1979 | 44 |

| 1980-1989 | 13 |

| 1990-1999 | 6 |

| 2000-2009 | 40 |

| 2010-2018 | 14 |

SVP Class Signs: A Special Tradition

By Dylan Panarra

NTID established the Vestibule Program in 1969 as a one-year general education program designed to prepare deaf and hard-of-hearing students to enter RIT bachelor’s degree programs. In 1970, the Vestibule Program was shortened and renamed the Summer Vestibule Program (SVP) in response to increased availability of NTID programs of study, especially those at the associate degree level. Offered in the weeks prior to the beginning of the academic year, SVP focused on preparing students for college life and placing them in courses appropriate to their interests and skill level.

Because of the variance in students’ programs of study—with some pursuing associate or bachelor’s degrees and others certificates or diplomas—SVP became a common reference point by which each entering class of students identified themselves. This identification with SVP year supplanted the graduation-year affiliation often seen among students at other universities.

One of NTID’s earliest traditions was for each SVP cohort to have a designated class sign. The sign for each SVP class was selected by the previous year’s cohort. So, for example, the entering SVP class of 2018 will be identified by a sign established by the SVP class of 2017. Each SVP class sign uses a “V” handshape and is unique from all others.

Every SVP class since 1969 has had its own sign. Many of them have been recorded by NTID faculty members Samuel Holcomb and Marguerite Carrillo. See the gallery

Sam Holcomb demonstrates the sign for the 1969 SVP class.

Rules for selecting an SVP sign

There are four rules for the selection of each entering class's SVP sign:

#1

The sign must be selected by the previous year's cohort.

#2

The sign must use the "V" handshape.

#3

The sign cannot duplicate any other class's SVP sign; each class sign must be unique.

#4

No inappropriate signs are allowed.

Conversations with My Friends

A project by NTID Professor Julie Cammeron

Frank Argento

Bob Baker

Gerry Bateman

Jane Bolduc

Gerry Buckley

Julie Cammeron

Jerry Cushman

Vernon Davis

Kathy Eilers-Crandall

Father Tom Erdle

Jean Guy-Naud

Peter Haggerty

Fred Hamil

Lin Hoke

Florene Hughes

Mary Jo Ingraham

Eugene Lylak

Father Mothersell

Liz O'Brien

Pete Reeb

John Reid

Sally Skyer

Jim Strangerone

Sally Taylor

Gerald Walter

Fred Wilson

Jimmie Wilson